What is Life?

Which things in nature do we call “living”?

If we were to go to another planet and find a variety of complex systems, from chemical reactions and climatological phenomena to towering tree-like structures that don’t have the same chemical building blocks as life on Earth, how would we sort out the living things from the non-living ones?

As a mathematical biologist, I’m especially drawn to questions like these in the philosophy of science. In math, we answer questions like “What is a number?” with axioms, such as the Peano axioms, and simply let logic sort out the rest. Math can be profoundly fun once one embraces both the freedom of axioms and the chains of logic. As a biologist who loved math, or a mathematician who loved biology, or both, I tend to look at the world with both lenses. However, anyone who does both math and biology will be known in a lab as the person to do statistics, and as the guy who did a lot of statistics, and who puzzled over questions like “what is life?”, I fell madly in love with information.

Forget “life” for now… what is information?

Information theory in mathematics has some neat, probabilistic definitions of information. Colloquially, I’d say information is anything that helps resolves some uncertainty - not all uncertainty, not some uncertainty on all things, but some uncertainty on some specific thing. Thus, information requires some things to exist before the concept of information becomes relevant: it requires other things about which we are uncertain, and it requires some capacity to sense things and use the stuff you sense to update your beliefs. There must be uncertainty, sensing, and computations in the mix.

Information is an observable thing that reduces our uncertainty about other observable things we haven’t sensed directly. If you measure a person’s height, but don’t directly measure their weight, the person’s height will provide some information about the distribution of their possible weights. If I tell you “it’s going to rain this afternoon,” then you’ve directly observed a statement from me and that statement carries some information, shifting your belief about what the weather will be like this afternoon depending on how reliable you think I am on that topic. If the CEO of a publicly traded company tells you that their company lost money and the world hasn’t found out yet, that would be “material non-public information” - if you short the company or sell your stocks after hearing that information, you will have committed the crime of insider trading.

Information is evidence. While there is a lot of directly observed and measured information in the world ranging from climatological data to stock prices and more, there is another large body of information that we observe indirectly and communicate with words. Atmospheric moisture and barometric pressure today may reduce our uncertainty about the weather tomorrow, and beyond the sensors of physical processes there is a vast world of social information regarding the companies, governments, people, parties, and other human affairs that we all want to predict.

This ecosystem of information we communicate with words, humans sensing things and sharing information about other human affairs, seems very much alive… depending on how you define ‘life’.

Life, as we define it in modern biology, is a process that replicates and metabolizes. These axioms aiming to define life - replication and metabolism - are the start of a beautiful logical journey comparable in wonder to the Peano axioms that form the basis of all mathematics. Life on Earth takes many forms, but from the simplest bacterium to the largest blue whale, all living things replicate and metabolize.

Like any definition, it’s good to give it a stress test. Some people disagree, for example, on whether or not viruses are living because viruses don’t contain their own internal ‘vats’ of chemical reactions like cells do. However, any effort to say viruses aren’t alive because they don’t metabolize “enough” relies on another undefined “enough”, or some undefined extent of metabolic self-reliance, that raises questions about all parasites that rely on hosts for replication.

I prefer the definition where viruses are very much alive. Yes, they depend on other organisms to persist, but so does every heterotrophic organism. Any organism that eats another organism relies on metabolic assistance from the primary producers that turned carbon dioxide into sugar in the first place - why should our definition of life split hairs between “metabolism” that breaks down glucose for energy inside a cell from “metabolism” that co-opts machinery in the surrounding environment, including a cell surrounding the viral genetic material, to accomplish the same miracle of replication?

Even plants, despite their superficial appearances of relying only on air, water, and sunlight, are not as self-reliant as they seem. Plants rely on chloroplasts in their cells, and chloroplasts in plant cells, like the mitochondria in ours, are the descendants of what were likely ancient intracellular parasites that slowly evolved towards the mutualistic relationships we see today. Chloroplasts and mitochondria divide, albeit under more or less strict control from their hosts, but I’m also hesitant to say that these replicating and metabolizing things are not alive given they, too, evolve and they, too, could at least in theory one day break free from the intracellular Eukaryotic prisons in which they currently live.

For a thought experiment: if I take a chloroplast and engineer it to have just a few more functions necessary for its own self-replication, and it proceeds to replicate in a broth that I brew, will I have made life from non-life, or will I have merely altered the evolutionary trajectory of a living thing that was simply living a very different, more co-dependent life before I stepped in?

If we say viruses are not alive, we run the risk of having to define metabolic self-reliance in weird ways that ultimately leave out some things we intuitively know are alive, things that evolve. If we focus on the evolution - the mutations and natural selection leading to forms better adapted to perform a task, and replicate again to perform the task indefinitely - then insofar as evolution, like pornography at a minimum, is something we know when we see it, then perhaps we should require our definition of life encompass all the things which evolve.

This may put the cart before the horse a bit, but imagine if we tried to define numbers with a set of axioms that prevented us from multiplying them. The Peano axioms, axioms that define the basis of most mathematics, from which everything like integers, real numbers, and even calculus can be derived, didn’t specifically define multiplication but rather arrive naturally at addition and from repeated addition we get multiplication. There’s some risk when we take a phenomenon, from evolution to multiplication, and use this to vet our axioms, yet if we wish to study that phenomenon then we sure as heck better have axioms in which that phenomenon exists. As I said, there’s fun in both the freedom of axioms and the constraints of logic - if a set of axioms doesn’t logically lead to the sort of system you’re hoping to study, you’re free to try other axioms!

Evolution is fundamental to modern biology, it helps us explain the origin of species and even tiny genetic elements such as the proteins that confer resistance to antibiotics, proteins that evolved from ancestral proteins and which can pass from one bacterium to the next with less co-dependence than mitochondria. Insofar as we want to study the evolution of life, we need a definition of life that neatly helps us study evolution.

Viruses evolve and thus, to me, viruses are alive. If viruses are alive, then perhaps we need to expand, and not narrow, our definition of “metabolism”. Viruses can be as small as mere DNA or RNA instructions wrapped up in proteins, and as they’re wrapped up they don’t necessarily metabolize - the proteins may just bind the surface of a cell and let the cell do the rest. The simplest metabolic step a virus must do is its coat or capsid must enable it to enter a cell, and its genetic material must engage with cellular machinery - none of this involves breaking down compounds like glucose to make their own energy… but remember, the cells breaking down glucose for energy are often not the cells that made glucose in the first place, so breaking down chemicals for energy directly doesn’t seem as important as replicating through some physical and chemical processes.

Such is life… a difficult thing to define. Yet, if we force some degree of metabolic self-reliance into our definition, then either our definition of “enough” self-reliance is unsatisfactorily arbitrary, or we define an extreme of self-reliance that no living thing meets as even plants that fix CO2 to sugar and break sugar back into CO2 don’t make their own sunlight, phosphorus, or other nutrients they need to survive.

If we believe viruses are alive, then we loosen our grip on “metabolism” in some catabolic sense of breaking down organic chemicals for energy and, slowly, our definition of ‘life’ broadens to more things in the world than just ‘cells’ and ‘multicellular organisms’.

Within bacteria, there are even small snippets of selfish DNA called plasmids capable of replicating themselves and triggering events that help the plasmids transmit from one bacterium to the next. Even within the human genome, there are elements of selfish DNA called “transposons” or “transposable elements” that can copy and paste themselves within our own genomes, replicating thanks to a series of metabolic reactions that duplicate DNA and insert the duplicated DNA back into the genome. Plasmids, transposons, viruses, and other replicating things that co-opt machinery found in nature evolve in elegant, beautiful ways, revealing Russian dolls of replicating things, life within life. The ecosystem biologists study is so much more than mere predators and prey, it is full of universes within universes of things that meet the criteria for a meaningful definition of life, things that evolve and change, that adapt and innovate new forms in curious ways.

Many of those who’ve wondered “what is life?” have found the lines hard to draw, the definitions elusive, and that is part of the beauty of life. Physicists studying the motion of objects had no problem defining a bowling ball or a planet, but biologists studying life live in a fuzzier world where it may be harder to delineate between the objects of their study. In a way, biologists live in a world of complex systems more akin in absolute curious weirdness as quantum physicists. Schoedinger’s cat and quantum tunneling and other weird consequences of quantum physics are well within the imagination of biologists who live in a world of weird.

For another geeky example beyond viruses, chloroplasts, mitochondria, plasmids, and transposons, consider lichen, the crusty green splotches you see on rocks.

Lichen is formed by a symbiotic relationship between fungi that can break down rocks and either an algae or bacteria capable of photosynthesis. Inside the fungi, you’ll also find mitochondria. Inside the fungi, I’d be surprised if there are no transposons, inside the algae you’ll find chloroplasts, and inside the bacteria I’d be surprised if there is some strange prohibition on plasmids. This consortium of cooperators, this Russian doll of replicators, has evolved such an intricate symphony of coordinated metabolic music that they are able to all replicate together, form spores and fly off to fertile lands with fresh rocks. If that isn’t just the coolest thing you’ve ever heard, now imagine this system evolving for millions of generations, with natural selection whittling out any weirdness so weird it lots its function yet allowing whatever functional weirdness arises by accident and increases fitness, the ability of this weird consortium to replicate by whatever metabolic means necessary.

Is Information “Living”?

I swear my musings on life and information are related. Bear with me.

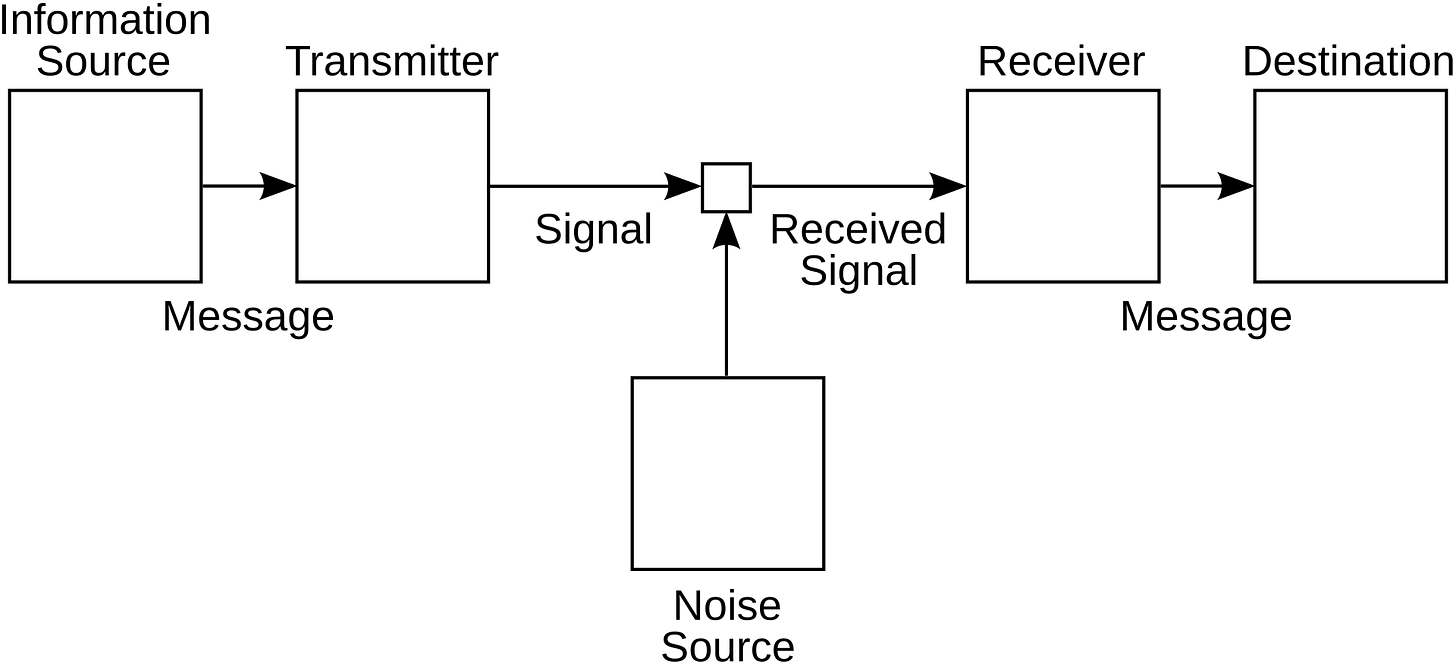

Let’s talk some more about information. In 1948, a gentleman named Claude Shannon wrote a paper entitled “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”. Dr. Shannon considered a message being transmitted amidst noise, with the goal being to maximize the fidelity of the message the receiver reconstructs.

Now, let’s put on our Weird Imagination hats and play with some fun analogies going from information theory to biology. A genome inside any given organism is a message for how to build an entire living organism, albeit with strict reliance on certain environmental conditions and how those organisms should respond to various environmental conditions (e.g. a plant’s genome is useless in soils without water; a chloroplast’s genome is useless if it finds itself outside a plant cell). That complex message in a genome is transmitted from one generation to the next through a noisy process of DNA synthesis. Although some mutations happen, and some mutations are so deleterious or bad for their host that the host can’t survive, some noise so unfortunately loud the message can’t be reconstructed, the large number of replicating living things, low rates of mutations, and perhaps other ways in which genomes are robust to the noise ensures that life goes on.

Clearly, there is an immense amount of information in living things and information theory is meaningfully applied to life.

I would argue that all living things can be viewed as information for some mathematical biological purposes, in that all living things are observable evidence that resolves our uncertainty about other biological phenomena. Every genome we sequence is a noisy message we receive from the past, a story of ecological and evolutionary events we aim to reconstruct. The functional forms of organisms contain information resolving our uncertainty about past events, from the hip bones and lungs of whales revealing their terrestrial ancestors to spikes on American plants such as mesquite revealing the story of their ancestors deterring herbivory by giant sloths.

In my wild imagination that likes to view biology from the lens of information theory, it’s also a fun exercise to view information theory from the lens of biology. Now that we’ve played with the idea that biological systems are information-rich, and the mathematical results from information theory provide a neat lens with which we can view some core biological processes, let’s look the other way. Let’s look at information from the lens of a biologist.

Sometimes information is communicated just once - a message is left on read, a tree falls in the forest with nobody there to hear it, a sensor measures something of little consequence. When information is communicated just once, I would call that “sensing”, such as the thermometer sensing the temperature in your home to control your air conditioner or heater. At the core of life’s replication is the implied existence of two things, namely one thing that leads to another similar-enough thing that we’ll call it a “replica”. There’s not much use in viewing the information from sensing as “alive” because while there are physical and chemical processes at play for sensing, there is no replication.

The information contained in your home thermometer might not meet our more expansive definition of ‘life’, but the larger system in which that information exists may as similar HVAC systems are built and modified through a noisy innovation process that combines plans, concepts, regulations, materials and technologies to create a similar system in many homes. As new homes pop up, so do HVAC systems that look a lot like other HVAC systems. The same brand label, the same combination of parts, albeit with slight differences in how the vents wrap around a home much like differences in the morphology of vines that grow along different wires and walls. Yet, as vines have the same leaves, the vents in your HVAC have the same metal or other tubes. Your heater has a source of heat and a fan, all built out of some materials and in some fashion in accordance with a DNA-esque design used to build the replica in your home.

We can take this mental exercise beyond HVAC systems to all manners of tools humans use and objects we create. The hammer has come a long way from the rock. Knives that started out as sharp rocks have diversified to a veritable rainforest ranging from butter knives and steak knives to machetes, swords, and more. With the sword or the knife there was natural selection for armor and shields, and armor and shields have evolved to span many forms, materials, and even functions from physical protection to symbolic crests and ornaments in creepy castles. The hammer, the knife, the bowl, our clothes, our homes, food recipes, soaps, toothpaste and every other object humans create manages to replicate by virtue of the way humans copy each others’ cool things, how we can either communicate designs and the protocols, or steal them, and make something similar.

Our tools replicate, and while the process of replication for, say, a hammer may be entirely reliant on the functions of another organism, such as a human, in a way it’s not much different from a virus, plasmid, or transposable element. Maybe viruses are unliving tools of nature, or maybe tools are living parasites of human productivity like viruses. Not all parasites are bad, you know. Don’t be worried - mitochondria and chloroplasts reassure me that even parasites can become our most beloved companions with time. Every time I go to Albertsons, Home Depot, or Costco, I stand in awe at the coral reef of foods and tools before me, the miracle of living things that replicate through a noisy process of mutation and innovation, even those things that rely on other living things in order to replicate in their noisy way.

I look at the toothpaste aisle with wonder. Your favorite toothpaste looks at you in the aisle of the grocery store crying desperately “buy me!” as desperately as a viral capsid seeks the receptors on cells it wants to bind to, because the more people buy that specific toothpaste, the more of that toothpaste the company will make.

Our adoption of tools from hammers and knives to laptops and iphones drives their replication. The R&D arms of innovating humans trying to sell more tools drives the mutation and diversification of tools. Today, in our globally connected economy with the internet selling any tool in the world money can buy, we are living through the Cambrian Explosion of human things.

The wonder I feel in the toothpaste aisle at Albertsons or browsing the rainforest of things on Amazon fueled my PhD on “competition and coexistence in an unpredictable world.” Fascinated by the common processes of replication and resource competition, I studied the mathematical similarities of “competition” between tropical trees, microbes in the gut, companies in the same economic sector, social and political groups replicating narratives in their quest for power, and more. While seemingly unrelated, all of these processes involve units of things that replicate and compete over limiting resources. While the manner of their noisy replication processes differs and while the nature of the things over which they compete and how this competition unfolds is very different, all of these systems can be modeled with the same math, from the same axioms, that we use to study evolution.

A single piece of information from a sensor may not be meaningfully considered “alive” because it doesn’t replicate, but tools, on the other hand, including tools that sense things from HVACs to drones, are forms of matter that contain information in their form and function, just looking at a tool gives a human ideas about what they can do with it, and because they replicate and mutate and evolve these tools may be productively viewed as living.

Seeing tools as information isn’t to ignore the utility of tools, but rather to focus briefly on the social process of humans communicating information with physical objects. If you see someone using a new tool, and it accomplishes something you want to accomplish, you will want the tool. Your sensing of the tool conveyed information to your brain about a thing you can make or buy, and that information led you to make or buy a similar thing. Someone else sees you with this new and cool thing, and receives similar information, and the replication and evolution of the tool goes on.

Information, like life, has a fuzzy definition such that many things can be seen as “information”, from the measurements on a sensor to the reflection of light off a tool sensed by your eyes and envied by your mind, to the words I’m writing to you now.

The words I’m writing to you now are alive. The words I’m writing to you now can change. The words I’m writing to you now can take new forms. The words I’m writing to you now can replicate and innovate in weird ways. The words I’m writing to you now contain information, albeit not the information you’ll use for predicting the weather or tinkering with your thermostat, but information you may choose to use to change the way you view the world, to resolve your uncertainty about the set of concepts and categories you want to use when you look at the world’s many things, from vines and HVACs to viruses and toothpaste.

“To be or not to be…”

“I have a dream…”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

“C’est la vie”

“Blessed are the poor and the meek…”

All of these words come tied to a constellation of additional words and concepts, names of books, movies, attitudes, and other pieces of social, historical, political, and other context. We can convey information sometimes by merely alluding to larger concepts with a preview of the thing, and thus the replication of information through words is not captured directly through a high-fidelity replication of the entire body of information, but through a slow reconstruction of concepts in human minds, and the activation of those concepts by various linguistic, symbolic, non-verbal or other means of communication. After all, sign language carries similar information as written language, but the words aren’t written or spoken, they’re gestured, and sometimes exaggerations in gestures add emphasis, sometimes with puns and manners of emphasis that aren’t available in written language.

When we see sign language as a way to convey information, it’s also useful to think of ways hearing people “sign” with non-verbals. Smiles, frowns, pointing fingers, shrugs, crossed arms and furrowed brows, crossed index fingers mimicking efforts to deter vampires, middle fingers, and myriad other gestures can convey rich information about how our emotional state, the physical environment, and more, all resolving uncertainty, and all replicating whenever somebody sees a gesture, remembers it, and repeats it in another context.

While language and the information we convey falls under similar axioms of life, it’s fun to play with how this is different. Just because a plant and an animal are both alive doesn’t mean they are the same, and studying the differences reveals a rich diversity in these systems we’re studying.

Words are symbols that represent concepts, ideas, or things, and humans have dabbled in symbols for hundreds of thousands of years. The evolution of human language reflects an evolution of the symbols we interact with, symbols that started off as simple as horses painted on the walls of Lascaux caves - information on the fauna present at that time and the behavior of ancient humans - to symbols representing complex concepts such as “quantum physics” or “life”. We humans gather and share symbols in fascinating ways. We latch onto some and reject others the way bacteria let some extracellular DNA change who they are while disposing of the rest. From the American flag to dialogue on what it means to be an American, our words and symbols evolve and compete.

Language is a very important form of information for humans, and the processes allowing the replication of language depend heavily on the humans present.

The following sentence, for example, contains more actionable contemporary information: “Current stock prices are overvalued, driven largely by overvalued tech stocks propped up by retail inflows and overly optimistic projections of the impact of AI on tech industry profits in the coming years.”

Insofar as I am a reliable source, you may use such information to change your own beliefs about the likely direction of various stocks (disclaimer: this is not financial advice, although I do personally believe the sentence above). If you were to go out and say the same thing to someone else, then that sentence, or the core concept in it, will have replicated, along with the information it carries. Not every human will replicate this information - whether or not they do may depend on many factors, such as how much the person cares, how much they remember, how much they believe me, and other motivations. Even where it is replicated, not every human who hears or reads it will pick up this information. Not every rock is habitable to lichen, not every host is susceptible to a given virus, not every type of toothpaste tickles your fancy, and not every concept you hear changes the way you view the world and the things you say.

Yet, information conveyed between humans can replicate. The replication of information involves social and psychological processes in humans and their social contexts, as well as the physical and chemical processes of neurons firing to assess the information, muscles contracting to speak or type in the computer in front of you, electrons moving through complex circuitry to illuminate your screen, and more.

Information is alive. You are bearing witness to it right this second.

Richard Dawkins famously popularized the concept of “memes”, a social and symbolic analog to the “genes” in biology. When Dawkins wrote The Selfish Gene in 1976, biology was in a blissfully innocent era, the biologist’s equivalent of Newtonian physics before Einstein’s relativity complicated everything. Biologist in the 70’s were empowered by the Francis and Crick’s discovery of DNA as the object of inheritance and the Mendelian concept of genes. Together, these findings along with Darwin’s theory allowed population geneticists and evolutionary theorists to imagine life being comprised of simple, discrete units - genes. Finally, biologists had their bowling ball, the atoms of life, the easily delineated units of “genes” that can be put together to form a living thing like bricks building a castle, genes whose dynamics can follow the Newtonian-like models for the dynamics of evolution.

From this blissfully innocent perspective, a very sharp biologist coined the idea that information, packaged in ‘memes’, may be meaningfully viewed as… alive.

But how do we delineate memes? If I say “it’s going to rain tomorrow” and you say to someone else “it’s gonna rain tomorrow” and they pass on the same message in a different dialect, then French, then Spanish and so on, it may be difficult to define the ‘thing’ that replicated through this noisy game of telephone and translation. The replication of information is very, meaningfully different from the replication of DNA-based genes, and the way memes, or symbols and words, glob together to form larger units that can be copied & pasted is also strange.

Thankfully, biology also got messier since Dawkins’ time. The moment we sequenced the first genome, we learned that life is not as simple as we’d hoped. Genomes - the entire set of DNA in a living organism - do indeed contain genes, but genes comprise a minority of the human genome. About 2% of the human genome contains the classic protein-coding gene of lore that Dawkins imagined in the 1970’s. The gene whose DNA transcribes to RNA that translates to a protein, from hemoglobin in our blood to keratin in our hair and beyond, is far less common than a giant mess of other stuff. While 2% of your genome encodes proteins, about 10% of the genome is believed to be of viral origin, scars and relics of ancient battles between parasites and hosts competing over the same replicating multicellular system, as if we carry within us a graveyard of replicators telling the story of our ancestors’ battles with viruses. The remainder of the genome is a mix of other functions or a mystery as to why it’s there.

It’s a mess. A beautiful, weird, fascinating mess.

The more we’ve learned, the more complex our view of life has become. As with genes, our view of memes and the information we replicate is complex. I doubt you will ever copy this entire article in a speech, yet there may be bits and pieces, maybe even less than 2%, that contains a mix of concepts and rhetoric that stick with you, that you use again, that somebody else hears or reads, and that goes on, replicating with the help of some human or machine metabolism, mutating, translating, and innovating how that part of our information ecosystem may be used.

The Timescale of Information Evolution

While human evolution has taken place slowly over millions of years from our common ancestor with chimpanzees, and while the long story of the evolution of cellular life on Earth goes back billions of years, the timescale at which information evolves is much, much faster.

To get meta, consider the information that biologists replicate when telling each other and their students the contemporary theories about life. In the early 1800’s, biologists thought all living things were made by God, and this story was replicated in classrooms and books, across many forms the same pattern of symbols and concepts was replicated. Slowly, evidence emerged on the age of the Earth, the shifting of tectonic plates, fossils and species in South America resembling those in the complimentarily-shaped African continent leagues away, finches on islands in the Pacific, dog breeds made by artificial selection from wolves, and more. All of this information, replicated in scientific literature in the mid 1800’s and whispered amongst scientists pondering how to put it all together, merged into the minds of Darwin and Wallace where they synthesized a new theory, the theory that live evolved through natural selection.

A new scientific theory is, in our more general view of life, akin to a new living thing. A new batch of symbols and concepts was bundled together, along with graphs (symbols) and logic (forms of language more likely to be replicated by scientists) and more, and this new bundle of information can be printed in books, summarized succinctly by professors, and passed along, replicating in the minds of others.

Beyond biology, Dalton proposed the elements (pun intended) of atomic theory in the early 1800’s, but atomic theory wasn’t widely adopted until Einstein’s work on Brownian Motion in the early 1900’s. As atomic theory rose to the fore in the early 1900’s, new methods for measuring the composition of living things emerged. The ecosystem of scientific information interacts in weird ways. Slowly, a world of humans communicating through scientific literature measured the atoms in living things, parroted their findings, and learned more information about the molecular basis of life, including the basis of replication and metabolism.

Francis and Crick discovered the double helix structure of DNA in 1953. At the time, it wasn’t clear that DNA was the object of inheritance, meaning it wasn’t clear that DNA was the thing that you copied and pasted from one organism to another to pass along the traits from the first organism. Along with that structure of DNA, Francis and Crick realized that the sequence of nucleotides, much like the sequence of letters and spaces on this page, may contain information and enable DNA to serve as the object of inheritance.

Dawkins’ book The Selfish Gene built on Darwin’s evolution, Mendel’s genes, and Francis and Crick’s DNA to flesh out a larger view of the things that evolve, from genes to memes. As Dawkins melded memes and symbols of science with logic into a book that replicated, science, and the information at the front lines of scientists’ curious whispers, continued to evolve. The first draft of the human genome was published in 24 years after Dawkins’ book in June, 2000, and analysis of that genome radically altered our view of what’s inherited… and how messy the packet of information used to make life really is.

The information biologists replicate in talks, literature, and pop-science blogs like this one to describe living things, their composition and their origins, has evolved. As new evidence emerges, it changes the epistemological suitability of the “hosts” of information, changing our ability to believe and willingness to repeat the things we hear. The fact that humans continue to synthesize new information, and that this new information directly impacts the force and fidelity of our replication of other information, paints a picture of a fascinating human information ecosystem in which information floats between us like plasmids moving between cells, where some information we contended with can later become core to our belief structure, whether scientific, religious, political, or otherwise.

Information evolves at the pace of evidence and narratives. In a world full of sensors, where every iPhone captures images and sounds, and our sensors merge with our words on social media to hash out narratives, the evolution of information is rapidly accelerating. The fact that I can write this mess of words today in the mountains of North America and it can be read as far away as the UK and Australia within seconds is a wonder of the modern world. As the Amazon rainforest is a sight to behold, so too is the internet, the grocery store, social media and its contest of memes, and more.

A biologist’s guide to information points to the fascinating ways that information replicates and mutates, that replication and mutation are axioms at the heart of life, and these processes lead to fascinating forms of creatures and concepts that fill our world. We live in a rainforest of functional forms of living things informed by their messy genomes, each genome a message from the past, and these living things communicate in ways that generated new categories of socially transmitted, replicating things. Now, we inhabit a wild world of tools and symbols replicating and mutating, competing over your attention on the internet, your money spent on toothpaste, and more.

Isn’t it beautiful, this world of transposons and mitochondria, toothpaste and memes?

And now add the novel viroid obelisks to your catalog of life, making their oblin proteins for no known reason nor consequence. Your effusively creative enthusiasm mimics Nature. Thank you, Alex

Your musings jogged an old memory of a physicist trying (imho) to avoid having to wrestle with the definition of "life"

https://www.quantamagazine.org/first-support-for-a-physics-theory-of-life-20170726/