Pluralism in US Public Health Policy

Were prominent scientists politically ethnocentric during COVID-19?

American Pluralism

We all make the mistake of thinking “Americans” have the same culture, the same beliefs & values. However, while united in our democratic experiment and the pot of money into which we pay our federal taxes, we Americans are a diverse, pluralistic people spanning a vast range of religious, socioeconomic, racial, political, and other beliefs and circumstances. Our “One Nation Under God” is a beautifully diverse anthropological mosaic of 340 million people from the tundra to the tropics spanning a surface area nearly as large as Europe.

Our built environments range from metropolitan wonders of the world like New York City to remote outposts of Innuit villages in Alaska. Our homes range from massive mansions and towering skyscrapers to homes on the prairie, rustic lodges, and desert hogans without running water. Many Americans are liberated from organized religion and free to roam the world as agnostic or atheistic, and others are devoutly religious members of organized religion who believe in eternal damnation, reincarnation, and more. We have cities advancing the technological frontier with 5G networks and iPhones in every pocket, and we have the Amish.

In our large and diverse country, a failure to apply standard public health practices of cultural relativism and appreciate American pluralism when conceiving public health policy can - and almost surely will - result in an overreliance on ethnocentric policy recommendations. If we put tech afficionados in charge without cautioning against ethnocentrism, we could easily imagine them accidentally making contact tracing apps for populations that include the Amish.

Ethnocentric public health policy is unethical; it can underserve groups of people underrepresented in science and public health policy positions of power, and it can undermine trust in public health officials. Our national and international public health policy is vulnerable to ethnocentric policy recommendations because science, like many sectors of our economy, has a diversity problem. While 18.4% of Americans are Hispanic, only 8.4% of epidemiologists are Hispanic; while 13.4% of Americans are black, only 5.4% of epidemiologists are black. While 23% of Americans are Republican, only 6% of scientists are Republican. I have yet to meet an Amish scientist, but perhaps that’s because most scientific work occurs online.

While contact tracing apps for the Amish are obviously ridiculous and slightly hilarious, there are real and tragic examples of ethnocentrism in science and policy disagreements in COVID-19. One particularly potent example of ethnocentrism in COVID-19 policy is the way scientists dismissed conservative policies in the contentious debate between the mitigation of viral harms through focused protection, and the containment of the virus through society-wide changes like lockdowns, travel and trade restrictions, and school closures.

Containment versus Mitigation

Containment and mitigation, the things we’ve been arguing about for over two years, are a false dichotomy of pandemic control. Yet, we argued this dichotomy and any historian trying to understand what happened during COVID has to understand the context of “containment” policies as opposed to “mitigation” policies.

Controlling a virus is done through a mix of reducing the viruses’ severity and decreasing viral transmission. We can reduce severity through treatments, we can reduce transmission through various behavioral changes and non-pharmaceutical interventions, and we can reduce both transmission and sometimes severity through vaccinations. The challenge with COVID-19 was that we had little in the way of proven safe, effective, and widely available treatments, and phase 3 trials for vaccines were not completed until late 2020.

For the entire year of 2020, we had no vaccines and the scientific questions centered on how bad COVID-19 would be if it ripped through a population without any mitigation, how much mitigation could reduce COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality, and what collateral damage our non-pharmaceutical interventions could cause. Pandemic public health policies were built on the foggy foundations of those unanswered scientific questions, and the central policy question we faced in 2020 was how far we were willing to go to reduce transmission in a gamble for vaccines.

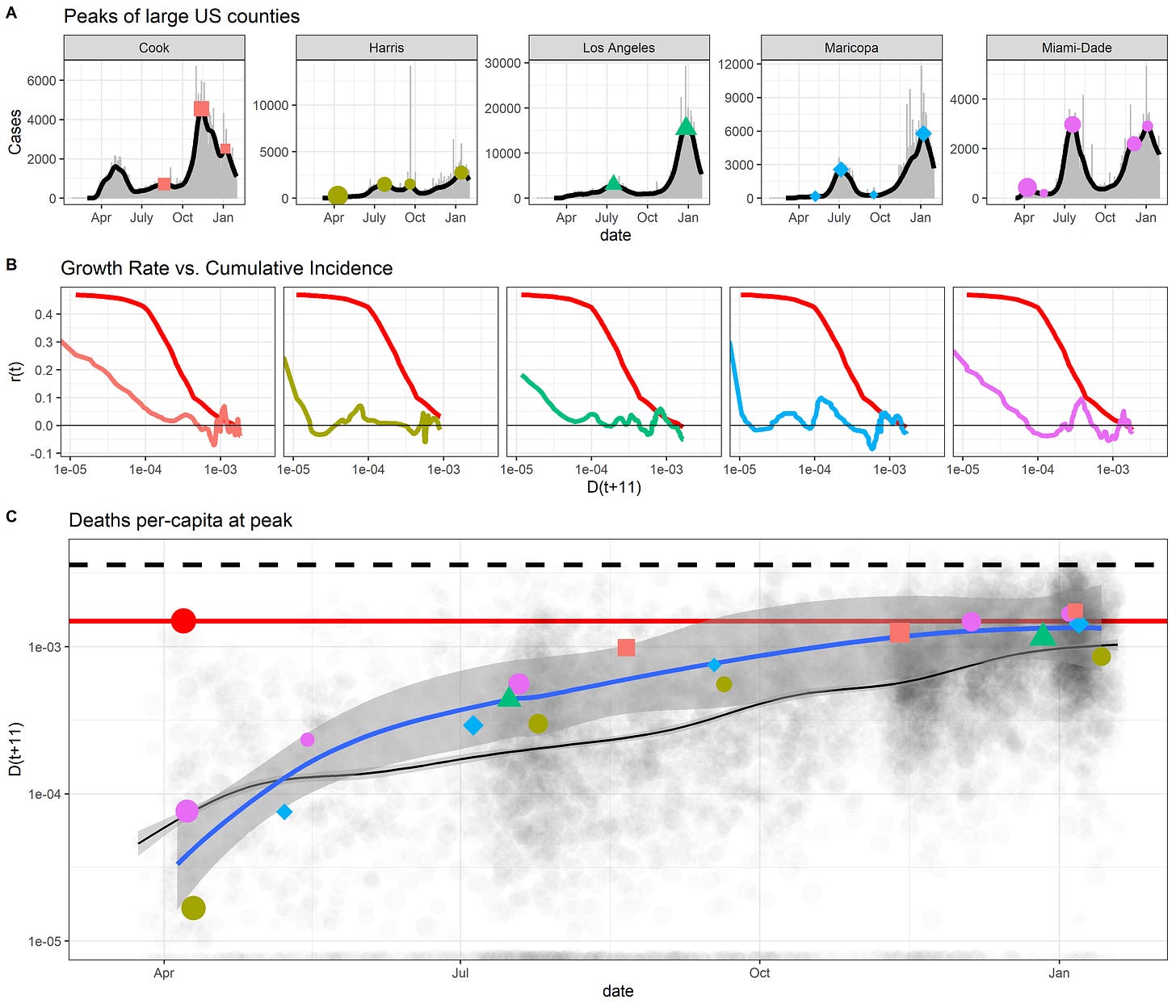

Containment proponents were willing to go the farthest to reduce transmission, all in a large gamble that vaccines might prove safe and effective and save more lives than would be lost from collateral damage from stringent COVID policies. Containment advocates believed that COVID mitigation efforts would result in 0.4% of the population in a US county or state dying for cases to peak, with up to 0.5-0.8% of the population dying by the end of the pandemic wave. For containment proponents, it was reasonable to force people to stay in their homes, to close schools, to restrict travel & trade, to do anything possible to stop the virus and wait for a vaccine, otherwise millions of Americans would die.

Containment proponents tended to avoid talking about the costs of their policy proposals but would propose to alleviate the harms caused by pandemic policies by increases in federal spending to subsidize labor. Put simply, the cost-benefit analyses of containment policies were flawed because costs were ignored & benefits assumed. Containment proponents imagined a federal government skilled and capable of tending to the diverse needs of Americans whose diverse lives were disrupted by unprecedented policies. As they ignored the potential costs, containment proponents saw no need for solutions for how to alleviate the harm our national actions caused to people outside our borders, such as >20 million people facing acute hunger predominately in Africa and Asia as a result of economic contractions from lockdowns, travel & trade restrictions, and widespread fear of a virus from messaging saying it could kill 0.6-1% of the people it infects.

Mitigation proponents, on the other hand, believed the estimates of COVID pandemic burden were highly uncertain or overestimates, that the estimated public health costs of pandemic policies were too low and real human and public health costs of containment policies may be higher, that the federal government may not be sufficiently nimble to meet the diverse needs of 340 million people whose lives were disrupted by outbreak control policies, and that harming people in the service of public health is unethical. They proposed abandoning the vaccine gamble and instead focus efforts on protecting patients at high risk of severe COVID-19 without requiring we reduce transmission to zero.

Mitigation proponents focused on protecting nursing homes, allocating tests & N95 masks to care facilities that accounted for nearly 50% of the deaths in early COVID-19 outbreaks. Instead of subsidizing labor for hundreds of millions of Americans with stimulus checks that could cause inflation while having no plan for dealing with hunger and poverty outside our borders, mitigation proponents argued for a relaxation of restrictions to minimize the harm caused by public health policies while we provide focused logistical and medical support for a few million people who are at high risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19.

In mid 2020, while epidemiologists warned about the harms of the virus, economists were warning of the harms from our responses to the virus. Signs of supply chain disruptions were emerging due to lockdowns, travel/trade restrictions, and changes in consumer behavior from messages of a highly severe pandemic all combined to increase poverty and acute hunger. People living on $1 a day no longer made $1 a day, and travel/trade restrictions disrupted the transportation networks used by humanitarian organizations to stave off starvation in the world’s poorest people.

The Great (Barrington) Debates

As noted, “Containment” versus “Mitigation” is a false dichotomy of disease control. However, a great deal of American deliberation of pandemic policy devolved into a tribal discussion of “Containment” versus “Mitigation”, with clear partisan assortment into camps as mainstream epidemiologists and liberals called for stronger federal and international disease control while many economists, conservatives, and some epidemiologists called for mitigation approaches that reduce collateral damage from COVID-19 policies. Scientists varied in their estimates of SARS-CoV-2 severity, the health and economic costs of pandemic policies, and the probable efficacy of various non-pharmaceutical interventions. Yet, despite these legitimate disagreements among scientists on the scientific foundations of pandemic policy, many scientists failed to acknowledge these legitimate disagreements, and many major institutional public health figures largely embraced containment policies and messaging while creating straw men out of mitigation arguments.

On October 4th, 2020, the Great Barrington Declaration was signed & released to the public, advocating for focused protection as a public health policy capable of reducing the harm of the pandemic and public health policies. The writers of the Declaration - Jay Bhattacharya, Sunetra Gupta, and Martin Kulldorf - were eager to declare that there was not a scientific consensus on public health policy, and that harming people through public health policy violates medical professionals’ Hippocratic oath to “do no harm”.

On October 8th, 2020, the head of NIH Francis Collins and the head of NIAID and US pandemic policy figurehead Anthony Fauci emailed one-another calling for a “devastating take-down” of the Great Barrington Declaration. While “herd immunity” is not mentioned anywhere in the Great Barrington Declaration, many containment proponents began misrepresenting focused protection as a “herd immunity” strategy.

On October 12th, 2020, the WHO Director-General called mitigation a “herd immunity strategy” and argued that ‘never in the history of public health has herd immunity been used as a strategy’. On October 14th, Rochelle Walensky (who now runs the CDC), Marc Lipsitch (Harvard T-Chan epidemiologist who now runs the center for outbreak forecasting & analytics at the CDC), Gregg Gonsalves (public health professor at Yale commonly lambasting the GBD on Twitter, who also goaded Fauci to step up the federal response to COVID-19 in March 2020), and Carlos del Rio wrote an article condemning the Great Barrington Declaration as a “herd immunity strategy”.

In the background of the Great Barrington Declaration, however, important scientific evidence was emerging. From the beginning of the pandemic, Sweden had adopted mitigation polices for COVID-19 and chose to refrain from closing schools, bars and restaurants to focus their protection on patients at high risk of severe COVID. For this ideological transgression of going against what EpiTwitter demanded of the world’s many people, Sweden was demonized by the scientific and public health policy messengers in mainstream US media outlets. Of note, Martin Kulldorf, one of the co-signers of the Great Barrington Declaration, is from Sweden. Rather than curiously understand Swedish culture, beliefs & values, and curiously learn if/how these cultural differences might underlie Dr. Kulldorf’s alignment with Swedish policy, scientists ostracized both Sweden and the Great Barrington Declaration authors. Many US epidemiologists and public health figures lobbed political criticisms at Sweden without a deep understanding of Swedish culture. These same pundits were driving US policy and pandemic media coverage in a manner quite dismissive of legitimate alternative views on both science and policy.

Pluralism and Public Health Policy

There was legitimate scientific disagreement on COVID burden and on the costs and benefits of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Containment proponents tended to say COVID burden was high, the costs of extreme NPI’s like lockdowns was low, that extreme NPIs are effective, and that softer NPIs to mitigate damage by focusing protection on those at risk of severe COVID would be unsuccessful and unethical. Mitigation proponents said COVID burden was uncertain but likely lower than that estimated by containment proponents, that extreme NPIs had high human health costs through starvation and poverty, that displacing harm from geriatric COVID deaths to young people starving in Africa is unethical, and that we can reduce all-cause mortality and morbidity by using softer NPIs that focus protection. The scientists disagreed.

In a massive, pluralistic country with deep political divisions about the relative roles of state versus federal governments, in which the CDC is a non-regulatory agency and states are granted powers not enumerated in the constitution, a small political monoculture of scientists pulled the reins of our country’s public health policy towards their political preferences. A field more disproportionately liberal than it is disproportionately white pulled US public health policy towards liberals’ preferences, most clearly when Gregg Gonsalves goaded Anthony Fauci into orchestrating a federal response to COVID-19 and when Fauci & Collins organized a “devastating take-down” of the Great Barrington Declaration that was admired by many independents and conservatives. The US federal public health policy messaging on COVID-19 was echoed by international health organizations like the WHO, which all echoed a false-consensus presented by mainstream media messaging on COVID-19, all of which presented overestimates of pandemic mortality to encourage society-wide changes, from lockdowns to bar/restaurant & school closures.

The platter of policy choices presented to Americans by leading epidemiologists was not an exhaustive, objective set of solutions to a scientific problem presented in an unbiased way. Rather, American federal policymakers and a coterie of closely connected epidemiologists decorated the policy platter with a favorable presentation of science that supported their personal policy preferences and public health narrative for America. Missing from the platter entirely were conservative policy choices, not because they were illegitimate nor proven ineffective, but because they were not the policy preferences of leading scientists and public health pundits.

Americans differ in their beliefs, norms and values. Some Americans value a strong federal government intervention to (try to) stop a pandemic. Other Americans may equally strongly, and with equally legitimate cultures and morals derived from their entire lives spent living in their communities, wish for powers of public health to be left to states and/or the people. Our constitutional system of government shares powers between states and a federal government, creating some disagreement among Americans about who should do what during the pandemic. Both liberals and conservatives are Americans; we differ sufficiently in our views to warrant a more culturally relativistic treatment in public health.

The science presented to Americans, such as estimates of millions of deaths under mitigation policies, was uncertain. Leaders in epidemiology and public health did not present unbiased accounts of the uncertain pandemic burden, they could not impartially present policies aligned with conservative values, nor did they put their minds to the task of maximizing the effectiveness of public health efforts within the constraints of conservative beliefs & values. Containment policies that became “the message” from public health figureheads in America, presented as the objective and morally superior answer to the pandemic, but containment policies were in fact subjective policy preferences from scientists and public health scholars who disproportionately come from one end of the spectrum of American political beliefs. Alternative policies such as mitigation, presented by the Great Barrington Declaration and adopted in places like Florida and South Dakota, sincerely aligned with the beliefs & values of many Americans, but these alternative policies - which should rightly be viewed as participatory public health from one underrepresented, distinct cultural group in America - were lambasted as unethical, immoral, murderous, “genocidal” and “eugenicist” (I wish I was joking) by the experts who asserted themselves as leaders of American public health policy. Such behavior was ethnocentric, unethical, and harmful to both Americans and public health.

When the rare beacons of political and scientific diversity in the field voiced their disagreements with this false consensus on science and policy, the heads of NIH and NIAID orchestrated a devastating take-down. Within 10 days of proposing to “orchestrate a devastating take-down” of alternative public health policy proposals, we saw exactly what Collins and Fauci desired. A public health call similar to “won’t someone rid me of this meddlesome fringe?” was followed by a flurry of hit-pieces coming from every corner of our information ecosystem, including blue check-marked Twitter profiles stamped as official, credible sources of information to editorials from famous epidemiologists in mainstream outlets like Washington Post, and even the WHO director general. The hit pieces are viewed by their supporters as necessary to maintain unity in public health messaging. However, under conflict theory they can also fairly be viewed as cross-cultural conflict in which one culture - liberals - had greater access to institutional public health power, from epidemiological prestige and media connections to official appointments at the head of our federal government, and the other culture was oppressed by the inequitable distribution of power. A conflict theorist’s view of COVID-19 containment versus mitigation debates can rightfully view that scientists, themselves immersed in cross-cultural conflict, used their institutional power to make conservatives’ - the other culture’s - preferred policies look stupid, unethical, and scientifically wrong. It undermines public health when public health leaders weaponize the privileged authority granted to scientists and public health leaders in order to suppress engagement and participation of minority cultures in the public health process.

The intention of this flurry of political hostility towards the Great Barrington Declaration specifically, and towards mitigation polices & their proponents more broadly, was to reinforce a message that mitigation policies would result in millions of Americans dead, that vaccines were necessary to save millions of American lives, and that Americans should support policies like shelter-in-place orders, school closures, vaccine mandates, that Brits should support a nationally orchestrated whack-a-mole game of tiered lockdowns, and countries with a long history of promoting civil rights should tolerate violations of civil liberties despite protests against restrictive policies and a lack of informed consent from subcultures in our pluralistic society.

The perils of public health monism

As mentioned above, the common defense of the blitzkrieg against the Great Barrington Declaration, and against scientists like Levitt, Ioannidis and others who spoke out earlier, was that these rogue scientists, by speaking their sincerely held views, were introducing conflicting messages, and conflicting health messages can produce adverse outcomes. If scientists estimated - however sincerely - that SARS-CoV-2 might not kill 1% of the people it infects but, rather, might kill 0.2-0.4% of the people it infects, then, it was argued, such estimates might trigger risk compensation and complacency that increases the number of people who die from COVID.

While conflicting health information can sow confusion and can lead to adverse outcomes, it’s also true that presenting a false consensus on scientific issues gambles public health’s credibility on uncertain science. Should the gamble go wrong, overconfident presentations of uncertain science can sow widespread distrust in scientists and public health officials precisely when trust is needed most.

Additionally, policy monism imposed on a pluralistic society can yield ethnocentric public health efforts that cause harm by proposing or forcing policies ill-fitted to the public whose diversity is not represented in the policy process. We talk about ethnocentrism in public health when advising Europeans and Americans on how to approach doing public health in places like Africa, but these anthropological principles still apply when working in our own country. It’s ethnocentric for liberals who have spent most of their lives in the NE corridor to project their culture, beliefs & values to think their preferred policies are the most appropriate public health policies for conservatives who spent most of their lives in rural South Dakota.

We’re different, and that’s okay.

The science is out, and the estimates of pandemic burden provided by containment proponents were, in fact, massive overestimates. South Dakota, Florida, and Sweden became the world’s control groups - these regions rejected costly containment policies in favor of focused protection policies. Yet, in mid-October 2020, the world’s leading epidemiologists and public health policy messengers claimed 0.4% of the population would die just for cases to peak, but in all of these regions following mitigation policies, cases peaked when 0.1% of the population died, with much more time left over for seasonal forcing to drive cases higher, yet cases declined without vaccines. Many people died from COVID, but containment proponents estimated that for every person that died in the saturated hospitals of South Dakota, 3 more would have died in their homes or waiting in line at the hospital. Those overestimates of pandemic burden were used to justify strong federal responses to COVID-19, devastating takedowns of different - smart and legitimate - policy perspectives, and other acts of hostile intolerance that limited the diversity of science & public health policy. Doomsday scenarios motivating containment policies never came to pass.

Beyond the false consensus undermining the science of epidemiology itself, the public health policy monism around containment strategies presented by mainstream epidemiologists and public health figures was not the only approach to public health policy in America, it was a reflection of the limited political diversity of the syndicate of scientists and public health policy pundits asserting a major influence on the American deliberative and policy process. By improperly using their scientific authority & positions in federal bureaucracies to invalidate conservative participatory efforts in public health, these mainstream epidemiologists and public health experts acted in a manner that was egregiously, historically ethnocentric.

It’s no surprise that liberals in this pluralistic country would want a stronger federal messenger for COVID-19 policy, as Dr. Gregg Gonsalves did when he reached out to Fauci in March 19th 2020 urging for stronger federal messaging. Liberals in the United States love delegating tasks to the federal government, liberals trust the federal government (especially appointees in executive agencies like NIAID), and they have a vivid imagination of what a nimble, sophisticated, and highly skilled federal government is capable of.

Liberals’ relationship with the federal government stands in stark contrast to conservatives’ views of the federal government. Conservatives view the federal government as an oversized, bureaucratic monster clogged with clumsy inefficiencies. Conservatives may better trust local messengers and local policies, including local policies that prioritize the right over the good, or they may balance competing risks of COVID and other causes of death, including deaths outside the US such as the >20 million people who faced acute hunger in Africa and Asia as a result of containment policies and widespread fear of COVID.

Many epidemiologists were disproportionately liberal and utilized their privileged positions as professors at elite institutions, leaders of federal agencies, and their connections with major media outlets to manufacture belief in estimates of pandemic burden that weren’t true and to pull US policy in liberals’ (their) preferred direction. The ethnocentric imposition of their policies onto a large and pluralistic country misrepresented scientific uncertainty and came at the expense of the country’s conservatives and all others grossly underrepresented in science, whose identities, beliefs, norms and values were not fairly represented in the American public health process during COVID. When diverse political values manifested in diverse policies across Florida, Texas, and South Dakota, the governors of these states became targets of waves of online hostility from scientists and public health experts, and epidemiologists labelled their activities as immoral.

To examine these ethnocentric actions, let’s imagine all of the epidemiologists and public health figures were American and British, and instead of discussing public health policy of Florida, Texas, and South Dakota, the regions proposing different policies were concentrated in Latin America and low-income countries in Africa. Most contemporary public health experts agree: it would be very unethical for a small contingent of predominately White Western epidemiologists to overestimate the severity of a disease to sow fear in historically oppressed/colonized countries full of people with different cultures and then use their larger media reach and unequal access to power to force their preferred public health policy agenda onto other people & cultures. Yet, somehow, this is exactly what happened within the US across cultural lines of our large and pluralistic country. The naked ethnocentrism of COVID-19 epidemiology and public health policy is not just undiscussed, many public health policy experts continue to hypocritically view such nakedly ethnocentric behavior as ethical when done entirely across cultures within America.

It would not be unethical to push one’s policies if Americans were all the same culture and/or if it were objectively clear when cultural relativism should be used to support participation in public health policy versus when public health policymakers must assert their ethics for an objective public health good. Of course, Americans are vastly multicultural and the public health norm against ethnocentrism, of valuing participation, is not objectively clear in when & where it applies and, furthermore, the often-egalitarian preferences of many in the field are socially constructed. We have to ask ourselves the uncomfortable question: do we really believe in the purported principles of tolerance and encouraging participation in a pluralistic world? When does the principle of tolerance no longer apply, and why there? Was it ethical for leading epidemiologists and public health figures to use their imbalance of power to demonize conservative participation in public health during COVID-19?

From a critical theorist’s lens, the treatment of conservative policies by scientists and public health officials during COVID-19 appears ethnocentric, a tragic yet predictable reflection of a field lacking political diversity and consequently trapped in a self-reinforcing ideological bubble, unable to empathize with people who are different from those in the bubble. This process is self-reinforcing because it’s hard to imagine many young conservatives would want to become an epidemiologist after this experience in COVID; in fact, this cultural monism is part of the reason why I left epidemiology. I grew up in New Mexico with many Libertarian friends in my community, with a family farm lacking potable running water like many of the homes in nearby Navajo Nation, and I found the lack of cultural and political diversity of epidemiology blinded the field and its leading voices to legitimate cultural differences in America. The exclusion of diverse voices from the discussion in favor of supporting a false consensus in science, and the unethical monism of public health policy derived from the exclusion of many American sub-cultures from the public health process, was unethical under the ethical principles central to science & public health.

The fields of epidemiology and public health purport - by their own social construct - to have ethical obligations to faithfully represent the science and to avoid ethnocentric policy when working across cultures. Mots public health scholars learn historical examples of how ethnocentric public health policies by White scientists caused harm to people of color in different cultures, such as well-meaning attempts to build wells for women in a Muslim country only to find that the trips to get water from rivers were essential for the women to discuss & protect one-another from domestic violence.

However, that same principle of tolerance for anthropological variation, the insistence on cultural relativism, was thrown out the window when it came to dealing with our fellow Americans. Epidemiology and public health, with such profound underrepresentation of conservatives in our ranks, united around an intolerant monism of policies that did not reflect the beliefs and values of conservatives, and other cultures in our pluralistic society. When conservatives proposed mitigation policies they would support, epidemiologists weaponized their expertise and media connections derived from their positions as ethical scientists to delegitimize these fair views from different cultures unrepresented in science. Within the scientific community the Great Barrington Declaration was criticized for being funded by a libertarian think tank, yet a culturally relativistic anthropologist would step back and acknowledge that libertarianism is not a bad word, it is a political philosophy held by 17-23% of the American electorate and held by almost no scientists. The scientific community’s demonization of political philosophies held deeply by many Americans, but not by scientists, is a damning example of poor diversity in the sciences yielding ethnocentric public health policy in a national emergency.

To put it simply, conservatives are people, too. Epidemiologists and public health scholars need to reexamine their anthropological ethics to clarify why conservatives in America were not given the same humanizing benefit of the doubt during COVID as non-White cultures are given in other public health responses around the world. It would be wrong to say conservatism is not a culture worthy of equal treatment, protection, and humanization by public health. A broader appreciation for and tolerance of cultural differences in our pluralistic society would humanize our anthropological variation and invite different cultures to participate in the public health process regardless of whether these cultural differences occur along racial, religious, regional, socioeconomic, gender, sexual, political, and other axes of human variation. The experiences of conservatives during COVID-19 may also hopefully inspire compassion among conservatives for the analogous - and extensively documented - experiences of people of color in America whose underrepresentation in positions of power has stymied policies that might help people of color and better reflect their values & the challenges they face in our society.

The literature trail of scientists attacking conservatives is long. The political and partisan hostility wielded by public health scholars in a time of crisis underserved vast swaths of Americans with different beliefs, norms & values who are underrepresented in science. A community of scholars were hostile, or at best apathetic, in response to cultural differences raised in epidemiology and public health in the middle of a global pandemic when we most needed diversity, representation, participation, and engagement from all of society not just an unrepresentative monoculture. These same public health scholars who demonize conservatives in America went to great extents, utilizing their unique power and privileges, to drive the American federal public health response to COVID-19.

Now, there are more COVID-19 deaths in red counties than blue counties, an effect largely attributable to lagging vaccine uptake in red counties prior to the Delta wave. As we stare down this unusual social/political determinant of mortality during COVID, an unsettling question we have to consider is that perhaps scientists failed conservatives during COVID much like scientists have failed many marginalized people throughout our history. Conservatives and others proposing mitigation policies were telling us what they would prefer to do, they were participating in public health. However, as epidemiologists demonized conservative policy proposals, and as the false consensus in science behind containment policies began to unravel, conservatives began to rapidly distrust science while liberal trust in science skyrocketed.

With the same seriousness we look at racial and social inequities in health, we have to examine these political inequities in COVID-19 mortality, and this partisan divergence in trust in science, and ask: did epidemiologists impartially serve all Americans during COVID? Could these inequities have been reduced if epidemiologists and public health officials had more compassionately, and less ethnocentrically, embraced American pluralism in public health policy?

Did Blue epidemiologists underserve Red Americans?

American pluralism in public health policy

I’ve focused on conservatives here because I have a few conservative bones in my body and can speak from experience. Conservatives are clearly an extremely underrepresented group among epidemiologists and public health officials. Conservative beliefs and values differ sufficiently from liberal beliefs & values to justify sincerely desired yet very different public health policies. Conservatives are not historically marginalized in the same way racial minorities, commonly the subjects of “cultural relativism”, were. On that topic, I personally hope this experience & my effort to connect these dots with a critical theorist’s lens may improve conservative appreciation for the experiences of marginalized minorities in America & the world, and perhaps reinforce a broader ethic of representation to improve policy efficacy in our pluralistic society, an ethic that can easily be incorporated into federalism and even Libertarian value systems. By being culturally distinct, by being so underrepresented in science, and by comprising a large share of people and even representatives in our polarized democratic republic, the conservative experience in COVID-19 tests our commitment to ideals of tolerance in science and our public health ethics aimed to avoid the harms of underrepresentation from non-inclusive work environments and ethnocentrism in science and public health policy.

In the case of COVID, it was Conservative policies that were notoriously ridiculed in an orchestrated manner by the dominant, disproportionately liberal political culture of epidemiologists and public health officials. Conservative think tanks’ propositions for policy responses to COVID were seen as corrupt or evil by many scientists with preconceived animosity for conservative groups. From one angle, scientists may see themselves as holding back a tide of misinformation and safeguarding message clarity in public health policy. From another, culturally relativistic angle detached from American partisanship, scientists in COVID may be fairly seen as being openly hostile towards, and thereby underserving, an underrepresented group in science during a time of deep partisan rifts and widening cultural divergence within America.

In our fiercely partisan times, is it even possible for scientists and public health experts, with their overrepresentation of one of two parties, to serve as impartial, unconflicted guides of their own country? Or do the political biases of scientists tilt the scales of policy and favor the scientific evidence supporting whichever party has more scientists?

We ask the same questions of race, of whether white justices are capable of objectivity in cases involving race. We ask the same questions of sex and gender, whether men on the Supreme Court can handle cases involving women’s rights objectively, whether straight justices can understand and remain objective on queer rights. It’s only fair, and in the interest of classical liberalism’s goal of tolerant pluralism, to ask the same questions of whether scientists in a polarized public are capable of objectivity despite their biased political composition.

The broader goal of embracing American pluralism is much larger than inspiring scientific tolerance across our partisan divides. The full scope of American pluralism has to consider race, region, socioeconomics, sex, gender, religion, etc., and the intersection of these. In public health, we claim to believe in a common ethical standard of cultural relativism, but that ethic was thrown out the window during COVID-19 when liberal scientists demonized conservative participatory efforts, let alone dissenting liberal positions (and there were many of those, too). Before the next pandemic, we must reinforce the ethical pillar of cultural relativism in public health with a fresh look at America’s many cultures, a deeper appreciation for American pluralism, and an unsparing debrief of which major subcultures were not adequately represented or tended to by epidemiologists or public health officials.

Rather than attempting to itemizing and binarize the constantly evolving continuum of American cultures, we must find ways to promote broadly inclusive public health policy and be open to testing our inclusivity with any dialectical cultural contrast in our society. Otherwise, one must find a way to define the superior cultures to follow in public health policy without violating the principles of tolerance & cultural relativism or abandon those ideals in light of an inescapable hypocrisy. I prefer the road of broad inclusivity and I can see a few ways to move towards this goal.

The Way Forward

The first thing we have to realize is that one size rarely fits all across our large country. While tech employees in New York City can work from home instead of riding the subway to work every day, people working oil rigs in Texas, ranches in Montana, and farms in Iowa may not be able to work from home. While many white people live in small homes with their nuclear families and can separate themselves from the grandparents, many Hispanic and Native American people live in large multigenerational homes with essential workers. In these large multigenerational homes, elders are often the primary caretakers of kids and in some cultures “protecting the elders” may resonate and benefit from specific kinds of support, from focused protection or focused policy action. Across our vast, heterogenous human populations of the US, a policy or a public health message that works where you live may very well harm people who live somewhere else, who have different cultures, beliefs & values. As one size may never fit all, it becomes increasingly important for scientists helping a pluralistic world to avoid political monism at all costs, to deliberately create space for alternative ideas.

Second, we have to appreciate our own limited positionality and enter rooms with a great deal of humility about what policies or messages might work for people from other cultures. Many predominately white epidemiologists living in the NE corridor said that “focused protection” and protecting the elderly could never work. In their communities and cultures, the elderly are exposed to the virus everywhere in dense metro areas, in buildings and on subway trains. From their positions, once prevalence is too high it becomes impossible for elders to protect themselves. However, in Native American tribes across the west, where there are no subways and people live inside single-family homes, elders are identifiable and revered members of the tribes; “protect the elders” resonated with tribal culture enough to became a motto behind communal efforts to focus protection from Navajo Nation in New Mexico to Blackfeet Nation in Montana.

In my wife’s Hispanic family, we implemented a focused protection approach to safeguarding Abuela, my wife’s elderly grandmother. Our focused protection prioritized reducing the risk of transmission to Abuela by utilizing our closely connected extended family and set up a program of ensuring the uninfected status of whoever is living with Abuela. Instead of demonizing focused protection, if scientists humbly acknowledged their unfamiliarity with other communities and asked “Okay, what are some examples of focused protection that would work for your community?” it’s possible we could’ve created space for Navajo Nation to share their story instead of listening to the same story from Anthony Fauci or epidemiologists in the Washington Post. It’s possible we could’ve shared our “Abuela Protocol”, and such a protocol may have proven useful for other closely connected extended Hispanic, Native American, and other families. When scientists step down from pretending to know everything about everyone, we can create space for diversity, for people from other cultures to share their experiences, values, and ideas.

Third, to overcome partisanship of scientists, we need to put more effort into seeing the merits of what other people are trying to say instead of trying to out-debate them. For example, whether or not focused protection works became an acrimonious debate, yet few containment proponents saw the merit that focused protection works at various scales. Fewer still gave benefit of the doubt to scientists & citizens with whom “focused protection” resonated. Focused protection provided a heuristic for individuals to prioritize their efforts, for households and families in many cultures to plan and prepare for the pandemic to protect the most vulnerable members of the family. Had leaders in epidemiology and public health been more tolerant and refrained from “devastating takedowns” of competing views, we could’ve come to agree that mask-wearing in subways and on planes are examples of focused protection, focusing our efforts on the most important settings. We focus protection when we reduce HIV transmission by providing needles for drug users as opposed to providing needles for just anyone, and so “focused protection” is central to public health policy: it is simply maximizing the cost-effectiveness of our efforts, and that position has merit in our national deliberation. At the national level, we implemented focused protection when we prioritized individuals at risk of severe COVID for vaccination, and focused protection could’ve increased the efficacy of our allocation of tests by allocating more rapid tests to nursing homes as opposed to giving everyone rapid tests with little instruction on how to maximize the cost-effectiveness of their own use of tests. There is merit to thinking about cost-effectiveness, and many conservatives love thinking about cost-effectiveness as they ‘stand athwart the train shouting “HALT”’, yet the merit of their arguments was lost by scientists who reflexively saw their “opponents” as wrong, and needing to be “taken down”. In fact, that scientists saw conservatives as “opponents” as opposed to humans and members of the public, was wrong.

That focused protection was controversial, and that the Great Barrington Declaration continues to be demonized by scientists at the time of this writing, is a damning indictment of the intolerance of an unrepresentative field of scientists. To this day, one wonders if the Great Barrington Declaration’s cardinal offense was not the inaccuracy of its science (which was corroborated) or the feasibility of its policy (which in fact connects the GBD with most public health policies) but rather that the wise words happened to be supported by an economic think tank many liberals classify as “libertarian”. Whatever a scientist’s political beliefs, when trying to guide American policy, one needs to remember that conservatives - and even libertarians - are human beings whose culture, norms & values come from their entire life’s story and are as sincerely held to them as liberalism may be held by scientists. If scientists wish to lead a country in a time of crisis, they need to drop their partisan swords and give all humans the benefit of the doubt regardless of the political party or political philosophy of the think tank, and scientists must retain an open mind. The people we may disagree with may simply be from a different communities, cultures, or contexts; they can have good ideas that work well for their communities, cultures and contexts, but we’ll only get to that level of understanding if we give them the benefit of the doubt and create space for dialogue in our deliberations.

To avoid harmful policy monism in the next pandemic in our pluralistic society, we need to limit federal and international messages to the core science, including the uncertainty and disagreements. Instead of suppressing scientific uncertainty and disagreements in a culture of online hostility for dissident scientists, we need to allow scientists to make their arguments without fears of persecution for their dissent from an intolerant monoculture. One should not have to have tenure to speak their piece, otherwise we limit science to the particularly unrepresentative ranks of tenured professors. Rather than pretend the next generation’s Fauci and Collins and Birx and Gonsalves can conceive the right policies for hundreds of millions of people across a vast range of human experiences in our country, we need to create a platform for pluralism that facilitates the sharing of policies and ideas among people at many scales, from households and businesses to counties and states, allowing others to peruse the aisles of policies and ideas across the US to find what works for them.

Finally, we need to train epidemiologists and public health officials to have greater awareness of positionality and to exhibit greater cultural humility when acting as scientists and public health leaders in a pandemic. When we enter into communities with fierce partisan rifts, especially when that community is the one we grew up in and in which we have our own strongly held partisan beliefs and cultural skin in the game, it is essential we leave our partisanship at the door and serve our roles as scientists and public health leaders in the most impartial way possible to leave no community underserved.

"Now, there are more COVID-19 deaths in red counties than blue counties, an effect largely attributable to lagging vaccine uptake in red counties prior to the Delta wave."

I have a lot of respect for you work in molecular genomic analysis, but you totally goofed on this statement.

Without adjusting for confounding variables like age, obesity rates, and socioeconomics, these differences between red and blue states is little more than a curiosity.

A 2016 article in the NYT written in the same vein ("The Pathway to Prosperity is Blue") used statistics of college education rates, average household income, and health indicators as "evidence" that Democrat policies generated a better quality of life.

What these foolish authors had failed to take into account is how poor people and retirees move from blue states to red states in search of lower costs of living and jobs (high-paying blue collar jobs are much scarcer in blue states due to excessively high minimum wages mandates and regulations that kill small businesses). Let's face it, not everyone is cut out for college.

This exodus of poor people out of blue states may play a major role in these demographic differences, which in turn, affect COVID mortality.