My favorite place to be is on a mountain, but lately I haven’t been climbing as many mountains as I usually do. Life has given me its own mountains this year and sometimes it’s valuable to share stories about other challenges we face.

My dad has always been someone you could count on to tell jokes with the skill of a professional, show up on his ATV or tractor, fix things around the house, or get excited about long road trips. But, unexpectedly, in late September 2024, my dad suffered a serious stroke and was hospitalized. The family came together to help, but from day to day, it wasn’t clear how much he would recover.

Despite the stroke, Dad’s sense of humor was intact and shone brighter than ever. As my Uncle Paul comforted my dad and asked how he’s been, my dad said through half of his face, “It’s just so scary… so depressing… to be perfectly fine one day, and the next day have my brain work as bad as yours, Paul.” Unable to remember which year it was despite repeatedly being asked by every nurse and doctor who came to visit him, my dad leaned over to me and said, “Al… somebody really needs to check on these nurses. Nobody knows what year it is!” When he finally got the year right, saying “Two thousand… twenty… four?” I congratulated him and asked if he could say that in a different way (‘twenty twenty four’ being the desired answer). My dad then twisted his face and said in a Transylvanian accent, “Tvo thousend Tventy four!”

I was scheduled to attend the 2024 Pandemic Policy meeting at Stanford, so I told my parents I’d stay in town, but my dad insisted I go to the conference. At times, in between talks with wonderful colleagues and scientists I had just met, I would be overcome with sadness, always wondering how Dad’s doing and what hilarious jokes I was missing.

When I came back from the conference, I engaged full-time in my dad’s physical, cognitive, and speech therapy. (There’s no hope for behavioral therapy for us Washburnes.) Helping my dad walk again, then walk farther, then throw tennis balls against the garage door, chop wood, play every game in the arcade, and more helped me ignore the usual crowd of scientists who are more intent on pushing narratives about Covid origins than in discussing science. I was grateful to my dad for helping me find a rewarding and valuable focus close to home.

Around Christmas, my dad neared the 3-month mark in his stroke recovery and was walking, talking, and cracking jokes. As I sang Christmas songs in my head and the smell of cookies filled our dining room, we had a lot to be grateful for. However, on Christmas Eve, my mom went to Urgent Care about a strange abdominal & back pain, and around 9 pm we received confirmation of her diagnosis: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), or pancreatic cancer. The chances of surviving PDAC are slim, and often, the cancer is at an advanced stage at diagnosis. We didn’t know if she had a week, months, or, fingers crossed, more time.

Christmas Day was memorable and poignant. We spent the day reliving old, happy memories and imagining what the future held. I wondered if my mom would be with us next Christmas.

Mom is a scientist and, before retirement, had researched heat shock proteins and the differentiation of quiescent and non-quiescent yeast cells after glucose depletion, related to the cell division cycle. Through her work, she was connected with a variety of Cancer Centers and was extremely fortunate to be able to get an appointment at Mayo Clinic for the following week.

We left for Rochester on New Year’s Day and by Jan 2, she had begun a series of diagnostic tests and oncology appointments that would allow us to understand the stage, operability, and other features of the tumor. During the day, we would go from one doctor’s appointment to the next, amazed by the efficiency of the medical system and quality of care at the Mayo Clinic. During the evenings, we watched documentaries about the Mayo Clinic and dove into the scientific literature together.

Between my mom’s experience in cell and molecular biology and genomics and my statistics and systems biology background, we gradually began to feel agency, climbing this mountain of PDAC together, albeit with my mom on the sharp end of the rope. Looking at the situation as a science experiment empowered us both and even provided a sense of adventure while facing this terrible and worthy opponent.

We had an “aha!” moment right after the PET-CT scan in which radioactive glucose is injected into the body, allowed to move around and accumulate in a tumor, and the glucose localization is determined via a scan.

Cancer cells are defined by mutations that lead to the loss of checkpoints during cell division. To support uncontrolled cell division, cancer cells need glucose, an abundant energy supply in the body. Cancer cells outcompete other cells for glucose because cancer cells over-express “glucose transporters” on the cell surface that pump glucose into the cell.

The intense signal on the PET-CT inspired us. They reminded Mom of the yeast cells she had studied, cells which were also “desperate” for glucose. Maybe the cancer cells weren’t actually growing as rapidly as the doctors thought. Maybe they are desperate for glucose. We spent the entire evening diving into literature on glucose and cancer cells, wondering not only what can be done in future research but, most importantly, what we can do today. Can cancer cells’ desperate need for glucose be used against them?

Late one night in an AirBnB in Rochester, Minnesota, after getting the plan for chemotherapy – FOLFURINOX, including 2 cell-cycle targeting drugs - we connected dots, used our combined scientific expertise, and devised a plan of attack for Mt. PDAC.

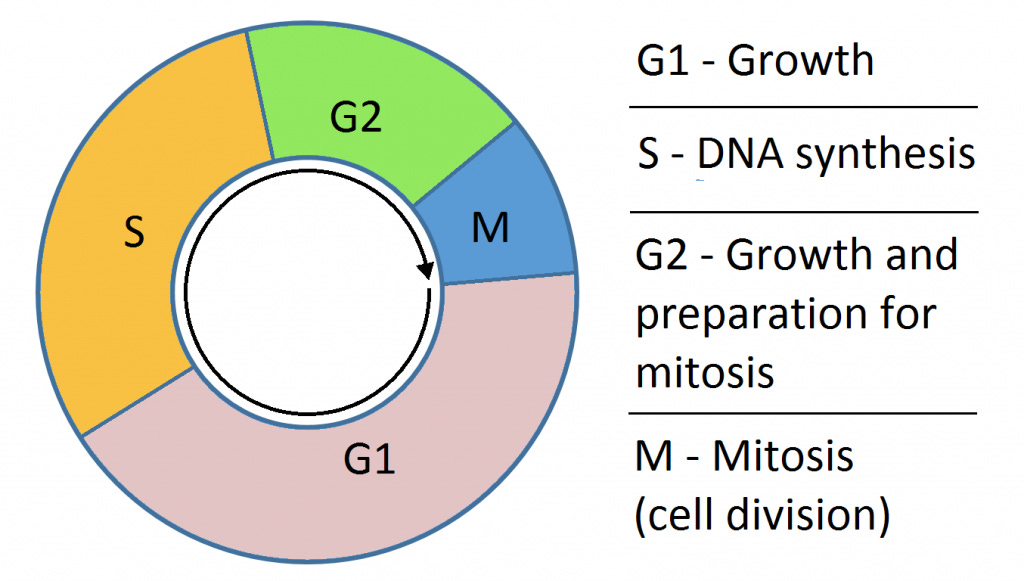

The mammalian cell-division cycle, how cells divide into two cells, has for major phases. G1 and G2 are “resting” phases. In G1, the cell “determines” if there are enough nutrients and other factors that allow it to successfully divide. DNA synthesis happens in the S-phase. G2 is the time when the cell assesses whether DNA synthesis is complete and M is the phase in which the cell divides into 2 cells. The chemotherapy Mom was to receive targets the S phase, making DNA synthesis impossible.

However, cells aren’t always dividing. Even cancer cells might slow down in G1 and pause there if glucose isn’t available.

We hypothesized that low blood sugar might slow cancer cell cycles so that, at the population level, cells “pile up” in G1 as they try to gather scarce energy and nutrients to divide. If it were true that cancer cell cycle dynamics are sensitive to glucose levels in the body, it might be possible increase glucose concentrations at just the right time to maximize the number of cancer cells in S-phase, just in time for chemo to kill them by disrupting DNA synthesis as chemo does. Thus, in our “Aha!” moment, we hypothesized that a glucose-pulse regime would increase the efficacy of chemotherapy by increasing the proportion of cancer cells in S-phase during the administration of S-phase targeting chemotherapeutics.

Seven months later, my mom is still alive and is classified as an “extreme responder”. The tumor has gone down in volume dramatically and has been metabolically inactive for 2 months (it no longer glows on a PET-CT scan). Her cancer marker has been normal or below normal for 4 months, and, other than peripheral neuropathy, my mom feels well. However, we aren’t naïve about PDAC. We are looking at the next phase, when individual cells, perhaps quiescent, are the threat. PDAC metastasis occurs even after the tumor is removed by surgery or killed by radiation. We think of these as guerrilla cells, and now my mom and I are diving back into the literature, including ongoing clinical trials, brainstorming how we can extirpate these scattered survivors before they form a tumor elsewhere in the body.

We anticipate writing a case study containing technical details of her tumor, dietary regime, compliance, and clinical outcomes, including a discussion of related literature, potential confounding factors, and our ideas for future research. I am sharing this sneak peek with you all as one of the mountains I’ve been climbing of late. Mt. PDAC has not yet been summited, but my family sits with my mom on a ledge midway up a menacing wall, together, grateful for whatever unknown mix of skill and good fortune has helped us make it this far.

If this protocol works (big if), it could be a cancer game-changer. The unique metabolism of cancer cells may provide an additional weakness of these cells, and metabolic control of cells may have the potential to make chemotherapy more effective. If careful regulation of the nutritional environment of cancer cells can increase the efficacy of chemotherapy, it could increase survival rates and even allow decreased dosage of the drugs that cause the worst side effects. We’re aware this is only a single patient, we could be wrong, and please don’t read this as medical advice, but if we can increase the efficacy of chemotherapy in future studies with larger sample sizes and better control over confounds, possibly even with different dietary regimes than our exact one, that could help PDAC patients feel more hope than we felt last Christmas, as well as other patients with other cancers that “light up” in PET scans.

Our climbs have been challenging this year. As I helped my dad get back to work on the farm and belayed my mom on her quest to kill PDAC, I’ve also left my national security mission work at Sandia National Labs to begin a new mission: working to advance health sciences and improve the health of Americans as a contractor aiding the NIH Office of the Director. I’ve been able to meet some truly incredible people working at NIH, astonishingly brilliant minds and passionate civil servants, all dedicated to improving human health and advancing health sciences. I could not be more excited for the mountains that lie ahead of us. I’m excited to continue applying my skills in artificial intelligence, infectious disease epidemiology, and risk-management to improve, to the small extent I’m able, human health and health sciences.

The mountains I’ve climbed lately have both built and revealed the character of my family, myself, the doctors at the Mayo Clinic, and more. We’re still going, and the mountains we have scaled have given us the experience and courage to go forward towards the next inspiring peak.

Below is the summit pic I’m most proud of this year: my dad smiling & standing upright, my mom smiling in-between appointments, and me helping them along their journeys next to a quote on the wall of the Mayo Clinic:

”The greatest asset of a nation is the health of its people.”

-William J. Mayo

Best wishes in all of your climbs!

Looking amazing, Alex!