A Scientist's Civic Duty

How to maintain this delicate relationship between science & society

We often take for granted the delicate relationship between Science and State.

In the United States, we formalize a separation of Church and State to protect our citizens’ freedom of belief and stop the State from favoring one religion over others. What is it, then, that enables the State to fund science, to establish entire institutes like NIH and foundations like NSF to dole out funds to research activities of various scientific paradigms?

Those who drink the drought of dogmatism view science as belief system like a religion, a proper noun: The Science. The Science is described as an encyclopedia of facts and a treatise of theories woven inextricably together with political priorities and value systems of the scientists advocating this view. Those who don’t believe The Science are considered every manner of blasphemer, from creationist or flat-earther to anti-vaxx or, in the furious eyes of Peter Hotez, Anti-Science.

Science, however, is not a belief system because new evidence is expected to change the beliefs of scientists and because at any point in time scientists propose opposing hypotheses and theories designed to be tested and rejected, so there is no One Theory or One Paradigm or One Hypothesis in which we are all supposed to believe. More accurately, science is a social system for sharing reproducible evidence, communicating different explanations for the evidence, and allowing others to provide evidence that corroborates or rejects our explanations. In such an ever-changing landscape of evidence, paradigms, and possibilities, the belief of the most successful scientists is spread across many possibilities in proportion to their likelihood, like the stocks in a portfolio diversified across sectors to accurately represent our uncertainty about what evidence or information the future holds.

The State allocates taxpayers’ funds to science, not The Science. While The Science is poisoned with politics and acidified with advocacy, science as funded by The State is a marketplace of ideas bubbling with intellectual entrepreneurs whose technologies can improve our health, our national security, and/or our economic prosperity. As citizens ought to examine the nature of their system of government and the civic duties like voting or jury duty that strengthen our civic system, we scientists ought to carefully contemplate the nature of our scientific system and the civic duties of a scientist that strengthen the system on which we all depend.

Most scientific apprenticeships - PhDs and such - require training in research ethics. Research ethics focus on what scientists must do with respect to their science and other scientists to preserve the integrity of our scientific marketplace. Research ethics are, indeed, core civic duties of scientists and they focus on scientists’ relationship with other scientists.

Fabricating data can pollute our scientific literature with falsehoods that waste critical resources and obstruct our technological progress. Thus, one must not fabricate data, as Proximal Origin Robert Garry is accused of doing in several of his manuscripts.

Undisclosed conflicts of interest can allow bad actors with misaligned incentives to pollute our literature with falsehoods, to pull a debate in their favor for financial or personal gain at the expense of the broader scientific community’s interests in truth and fair competition of ideas. Thus, one must disclose conflicts of interest, as Peter Daszak and Jeremy Farrar failed to do when not disclosing their work with or funding of the Wuhan Institute of Virology while calling lab origin theories “conspiracy theories”, and as Eddie Holmes failed to do when not disclosing his own research with the Wuhan Institute of Virology while publishing the Proximal Origin article calling lab origin theories “implausible”.

It’s also important that we list all authors of a manuscript and acknowledge if any other parties played a role in prompting or encouraging our publication, as a failure to do so can allow conflicted parties to pull the puppet strings of scientists and, again, pollute our literature with arguments presented as objective expert perspectives but, in fact, representing the interests of those in power. Thus, one must not ghostwrite articles on behalf of others, especially others with conflicts of interest, as Andersen, Holmes, Garry et al. did in Proximal Origin when calling lab origin theories “implausible” on behalf of Fauci, Collins, and Farrar, funders of the labs in question.

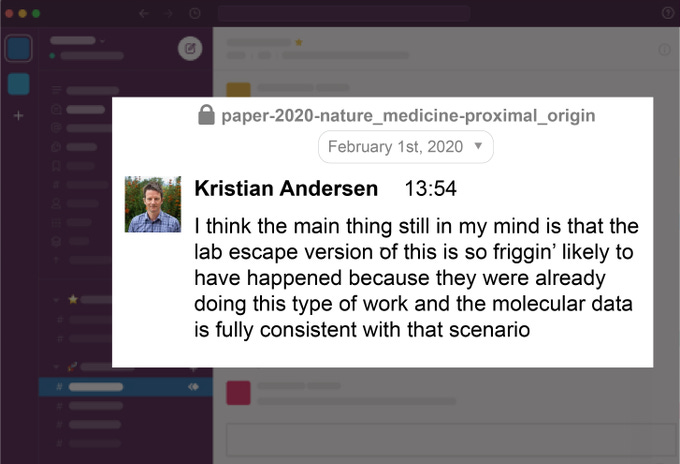

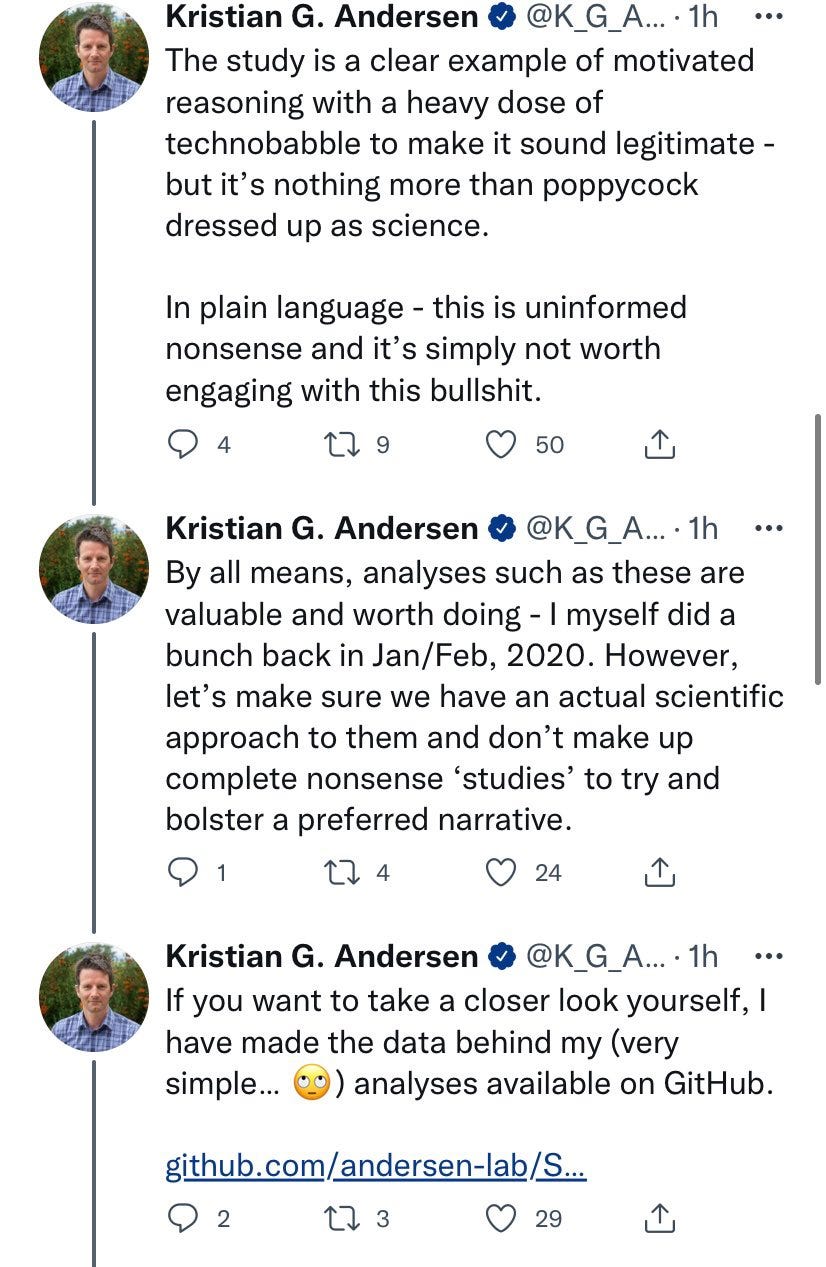

There’s a lot more to research ethics, from issues of human subjects research to data sharing, peer-review, and more. At the core of research ethics, however, are simple rules. Be honest, so don’t write an article calling a lab origin implausible if, privately, as Kristian Andersen said, you believe a lab origin to be “so friggin likely”. Be transparent, so don’t hide your conflicts of interest or ghostwriters of your work. Be kind and constructive when discussing science with others, so don’t rush to a room full of 100,000 followers to misconstrue someone else’s work “poppycock” or “Kindergarten molecular biology”, as Kristian Andersen did of my own work with Valentin Bruttel and Tony VanDongen.

While research ethics are essential components of a scientists’ civic duty, there are not exhaustive. There are other components of a scientists’ civic duty which concern the relationship between scientists, the citizenry and their representatives who fund science.

When speaking with the media or citizens or their representatives, it’s essential to represent voices other than your own and attempt to present alternative sides of a scientific debate. I say this as a scientific consultant - there were many times when I was the only or the primary scientist providing consultations to a manager, and thus it was incumbent upon me to fairly represent competing views to ensure the manager saw the whole picture, not just the paradigmatic snippet of the picture I was painting. If you can’t provide a steelman argument for a competing view, then you may not be qualified to discuss the issue at hand. A recent paper interviewing scientists who presented themselves as experts on viral origins surveyed the experts’ beliefs in the origins of SARS-CoV-2, yet a shocking 78% of those interviewed had never heard of DEFUSE, the 2018 grant by Peter Daszak proposing to make a virus in Wuhan precisely like SARS-CoV-2.

Why did these 78% of scientists interviewed feel entitled to speak so assertively on this issue, having not yet done their homework? Simply being a professor does not make one knowledgeable, or one’s knowledge necessarily useful, about every single scientific advancement or debate in the field. While academia creates a hierarchy of power and prestige that leads many professors to believe they are automatically qualified to speak to large audiences on any topic, such arrogance undermines the relationship between science and the general public by providing many instances where scientists - the experts, as represented in the press - pontificate assertively and overconfidently, only to be later proven completely wrong.

The greater the arrogance, the greater the hubris, the greater the fall, as we witnessed countless times throughout COVID. The public was told 3.4% case fatality rates and forecasts of millions of US deaths in unmitigated outbreaks only to find otherwise in states like Florida or South Dakota.

In the early outbreak, prominent epidemiologists who were professors with large followings and many managers’ ears tuned into their every word, claimed cases would double every 6-7 days when there was evidence supporting faster growth, 2-3 day doubling times, and the fixation on 6.1 day doubling times caught managers like Governor Cuomo by surprise when they suddenly saw 2 day doubling times in ICU arrivals across providers in NYC. Had Governor Cuomo been given less overconfident, more representative consultations, he may have been able to brace for the possibility of a rapid surge in March by reacting to the discovery of early cases with messaging to the general public to mitigate transmission of respiratory viruses by, where possible, increasing ventilation, avoiding crowded spaces and such.

Vaccines were touted as safe and effective under the false impression that the public needed overconfident proclamations of safety and efficacy in order to trust vaccines, and trust science. What happened, instead, was that risks of the vaccines became known, and by the Delta wave in 2021 the inefficacy of vaccines to protect against infection became known. The public was told overconfident proclamations only to learn such proclamations were wrong. Scientists cried wolf, and not surprisingly the public slowly lost trust in the scientific authorities.

A lab origin was called a conspiracy theory by Peter Daszak, implausible by Kristian Andersen et al. who were prompted by funders of Peter Daszak and the Wuhan labs. The words of these conflicted scientists were broadcast by Fauci himself who promoted Proximal Origin as authoritative, and Farrar retweeted Proximal Origin as putting down conspiracy theories, yet neither acknowledged their role in prompting the manuscripts they promoted. By some currently unknown networking of scientists with media outlets, outlets like the New York Times, The Guardian, and The Atlantic began publishing synchronized mass-media campaigns for a series of papers published by these authors, mass-disseminating their overconfident scientific proclamations to the widest possible audience.

“New Research Points to Wuhan Market as Pandemic Origin”, proclaimed the New York Times about studies quickly found to be based on bad statistics and buggy code. “The Strongest Evidence Yet that an Animal Started the Pandemic”, blared The Atlantic about a study quickly shown to have been not only unethical in scooping data from Chinese scientists, but also irreparably flawed by having cherry-picked a single sample with a raccoon dog and SARS-CoV-2 while not presenting the obvious finding that raccoon dogs were negatively associated with SARS-CoV-2.

Scientists misleading managers during consultations about an upcoming pandemic. Scientists acting as propagandists to push flawed finding to mass-media outlets. Funders of scientists promoting the work they prompted without disclosing the role of funders in the work.

What the hell is going on here?

The questionable civic engagement of scientists on epidemiological issues of case fatality rates, growth rates, vaccines, and more are in some important ways distinct from the issue of the origins of SARS-CoV-2. Epidemiologists inhabit an extremely hierarchical field with a few large institutes and even fewer famous big-names driving the lion’s share of publications and funding, allowing them to oversee small fiefdoms of many young scientists capable of pushing out many more papers than smaller names at smaller institutes with less funding, even if the latter stumble upon good or better ideas. Virologists, meanwhile, also inhabit a world of similar fiefdoms but additionally their field faces the possibility that their colleagues caused the worst man-made catastrophe in human history, and the research many of them advocated for, conducted, and funded may be viewed by the general public as almost criminal when the general public becomes aware with how cavalierly their deaths were considered by Fauci, Farrar and others “worth the risk” for new vaccines like the not entirely safe and modestly effective ones delivered during COVID.

There is a similar pattern, however, in the engagement of these scientists with the general public. If I had to put a lay spin on it, I would call it “elitism”. Scientists are prone to thinking that they are experts, and the mere concept of “expert” introduces a dialectical contrast of the “non-expert”. In an almost Freirean sense, scientists who self-identify as experts become epistemological oppressors required to lead and guide the epistemologically oppressed. Meanwhile, experts lead but one fiefdom and compete with others, and other fiefdoms with different ideas, especially those that coincide with different political views, can be viewed as intolerable, wrong. Hubris is an intellectual righteousness that poisons the mind until all you can see is your own view, and that is not just a waste of an imaginative mind capable of viewing so much more, but it can be dangerous when given credibility in management consultations or mass-media propagation.

It was elitism that encouraged scientists to focus on the WHO’s 3.4% case fatality rate to ensure the lesser public is appropriately afraid. Anyone who came under 3.4%, including myself, was a “COVID minimizer” who risked sowing complacency and risking deaths of millions of what they assumed were sheep-like people mindlessly following the advice of Fox News. When John Ioannidis or Jose Lourenco + Sunetra Gupta et al. merely pointed out the error bars in our estimates of upcoming pandemic burden, they were attacked by elitists who worried the foolish public could not understand uncertainty and make decisions in the face of uncertainty. The same false assumption of a stupid public drove some elitists to overstate the safety and efficacy of vaccines, fearing that any wobble, any uncertainty or sub-optimality of our tech, would sow doubt in The Science and sow doubt in vaccines across the board.

But the elitists have had it all wrong from the beginning. The role of scientists and science is not to lead the public - that is the established role of the representatives, the governors, the presidents, the managers we consult. Scientists are merely the umpires of universal forces and phenomena, and whenever we bias our calls to achieve the desired social effects we will undermine the sport and endanger our entire enterprise in the eyes of the public. The role of scientists and science is not to peddle and propagandize one’s paradigm, although the competitiveness of science may tempt one to do so. Scientists must be humble, study competing paradigms closely to understand them fully, and trust that evidence will reveal the truth. While we desperately want our theory to be right, no scientist should ever tilt the scales of truth, least of all in mass-media campaigns that risk misinforming the public about the critical issue of whether or not our colleagues’ risky research killed 20 million people.

It’s been shocking to see not only the atrocious research ethics and abandonment of civic duties of many scientists during COVID, but also to witness the complacency of colleagues in the face of such grotesque scientific misconduct and misbehavior.

If the COVID-19 pandemic was caused by a lab accident, then it means 1 million American citizens and 20 million worldwide died by the arrogance of our enterprise. Before tilting the scales in favor of your own theory for miniscule career benefits, consider the families crying at the news of their loved ones who died while intubated in an unreachable room. Before propagandizing your work, consider the funeral pyres burning in India and how the air smelled, imagine how the sirens rang through the streets of New York City in March of 2020 after 2-day doubling times clobbered a global metropolis. Before advocating for risky research as “worth the risk” as Fauci did, consider the 60 million people who suffered from acute hunger, imagine feeling the stomach pains of 60 million people going weeks to months without adequate nutrition because one bureaucrat looking to be in the history books thought it was worth the risk. Before misleading congress or other managers, as Andersen did when he said he didn’t have a grant before NIAID when prompted to ghostwrite for Fauci or as Daszak did when he claimed he planned to conduct his risky research in UNC and not Wuhan, think about the over 100 million kids thrown into multidimensional poverty during the pandemic, think about the millions of kids who dropped out of school and the grants they will never receive, the research they will never conduct, and the opportunities they will never have due to their stunted educational attainment during the pandemic.

Scientists have a delicate relationship with society. We have the privilege of doing research funded by taxpayers, and we must never forget the great responsibility that comes with such funding or what we owe the taxpayers in return for their support. We don’t just owe them a scientific system with ethical conduct of research, we also owe them the full, transparent, level-headed truth about the risks of our research and the crises our world faces. We owe the public a wise humility, an ability to educate and inform of evidence and competing paradigms without monopolizing the press or demanding to be followed. Scientists are not elected officials, we are not governors, yet we are often given a privileged position of consulting such officials. If we are honest and unbiased, the managers we consult will be better able to choose a course of action that represents their constituents and leads them to prosperity, even if that course of action is not the one we scientists-as-citizens would pick. When scientists are dishonest, biased, elitist, and unkind, they diminish the delicate relationship between science and society, undermining both.

It’s essential we teach scientists these softer virtues. In an enterprise of fierce paradigmatic competition, where failure to hype up your own work can lead editors to see it as lacking impact, where cutthroat politics can determine appointments and access to or control over lines of taxpayer funding, where gentle wisdom can be shouted over by bullhorns, there is a real risk that the scientists our system selects are not the scientists our society needs. I encourage scientists the world over to find ways to elevate these epistemological virtues, to coach civic duties, as these are the moral ties that binds us to society to begin with.

In the meantime, I hesitate to say this but in the spirit of practicing what I preach, I encourage the general public to not fully trust what the experts tell you. Because today’s experts are often selected by a system that rewards peddling and propaganda, arrogance and elitism, many of those who will volunteer themselves as authoritative may mislead you, they may view you as too stupid to hear the unfiltered truth or too gullible to be told about the uncertainty or the confidence intervals.

The only way for society to find the truth from such a messy social system is to ask scientists to represent opposing views and estimate uncertainty, then ask those who advocate for opposing views and ask them to do the same. Continue with this process and slowly you will find those honest and wise scientists willing to sacrifice their precious theories to the guillotine of evidence for the greater good and select them as consultants over the motley crew of narcissists, elitists, liars, propagandists, and other colleagues.

I have no problem calling the likes of Dazak, Hotez, and Andersen unethical money-grubbing-narcissist-elitists-liar-propagandists … but scientists? Nope.

Great article! This would make a great great reading assignment for a science undergrad ethics course, and could spur good discussion.