We’ve all heard of finches’ beaks.

But have you heard of the hydrolysis of cyclic amides and esters? It’s basically the same thing.

Bear with me here…

A foreword on my love of your beliefs

We’re going to talk about evolution here but, before I do, I just want to acknowledge that many people have beliefs about the origin of the universe that conflict with the theory of evolution. I’m not trying to proselytize. I honestly don’t know where the universe came from and I still can’t escape Cartesian doubt that it might all be a dream or we might live in The Matrix (granted, I don’t use this theory of Cartesian doubt to write papers or make many life decisions). Rather, I aim to provide a perspective that I find beautiful, intuitive, and useful for anyone interested in studying biology formally and quantitatively.

It would be nice if we could find a way to “put on” theoretical hats without needing to colonize each others’ minds. As surely as I can put on my philosopher’s hat and acknowledge I might live in The Matrix or that I have no clue what it’s like to be a bat, I can also put on my biologist’s hat and assume there is an objective universe we’re all able to measure (perhaps it’s just the code of The Matrix that we’re learning, if I needed to unify these beliefs?) and we can certainly draw analogy between echolocation and our combined ability to hear echos in a cave and detect where sound is coming from to help us intuit what we should measure in studies of echolocation. As a theoretical biologist, I put on different theoretical hats all the time to test theories - I put on a natural origin hat to ensure I fairly examine evidence from perspectives different from my own lab-origin hat for SARS-CoV-2.

While science is often a battle of beliefs, and evolution by far the victor in the modern battlefield of biology, I’m not going to go into aboriginal cultures and force them to adopt our scientific theories of evolution or time because that would be culturally insensitive. With that same cultural sensitivity, I’d like to respect your beliefs as well, even if we’re neighbors or heck even if we’re cousins. If your beliefs conflict with the theory of evolution, then don’t worry, I’m not trying to change you. Instead, I invite you to just wear this hat of modern biology for a moment and see the world through this beautiful, empirically useful lens of evolution. When you’re done, please feel no obligation to keep wearing this hat - you can hang it up on the wall on your way out the door and you’re free to believe whatever you’d like. I respect that.

Heritability in Babies, Dragons, and Birds

I loved dinosaurs as a kid. I came to appreciate lizards as something like modern dinosaurs, and so I loved lizards, too. My parents saw value in me learning how to take care of animals, so they bought me one lizard, then two. By the magical mathematics of biology, 1 male lizard + 1 female lizard became 32 baby lizards in the first generation. For several years, these parents made offspring, some of whom I kept, raised named, fed, and loved.

The bearded dragons that I bred had some predictability in the offspring they made. The eggs when they were first laid were little baskets of mystery, but something we take for granted if we put on our philosophical-hat-of-infinite-possibilities is that those baskets of mystery hatch into something like their parents. Fortunately for my parents, and much to my imagination’s dismay, a bearded dragon egg can’t hatch into a frilled lizard, a Komodo dragon, a saltwater crocodile, or other distant relatives of bearded dragons. I couldn’t conjure a T-rex from my lizard eggs. The predictability of offspring has a name I came to learn and appreciate much later: heritability.

While traits are heritable, and bearded dragons produce bearded dragons, that doesn’t mean bearded dragons stay the same over the course of evolutionary time. Bearded dragons breeders are still artificially selecting other bearded dragons to have distinct color morphs, selecting the offspring that glow bright orange and preferentially breeding them to have another generation that skews more orange than the last. As people breed dogs to have desirable looks and behaviors, lizard enthusiasts do the same. As a kid learning about lizard breeding, my mom the biologist pointed me towards an OG guy named Charles Darwin and his theory of evolution.

Anybody who’s heard of the theory of evolution has no doubt heard about Charles Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle and ol’ Chuck’s trip to the Galapagos Islands. On that remote archipelago off the coast of Ecuador, we’re told, Chuck observed turtles and finches that varied slightly from one island to the next. Chuck collected specimens as data points that helped him conceptualize & make the case for his theory of evolution.

We all know how Darwin’s story goes. Lesser known is a modern follow-up of Darwin’s Finches by Peter and Rosemary Grant, two lovely scientists I had the pleasure to know during my graduate studies at Princeton.

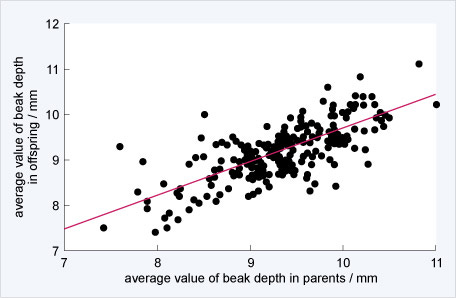

While Chuck collected a cross-sectional sample of beaks at one point in time, Peter and Rosemary Grant followed the birds for 30 years to witness evolution in their lifetimes. The first step towards demonstrating evolution in nature is to quantify the heritability of traits. “Traits” are ultimately anything that we can measure about an organism - it could be the color of a bird, the number of limbs on a creature, the size of a bird’s nest, the decibels of a whale’s song, the binding affinity of a virus to a particular host’s receptor, or the depth of a beak.

Peter & Rosemary measured the depth of a bird’s beak. Not only do finches beget finches as lizards beget lizards, but within birds there is variation in the depth of a bird’s beak and parents with deep beaks tended to have offspring with deep beaks. This heritable variation is a necessary precondition for evolution. If there were no variation, then there’s nothing to select, whereas if there’s no heritability then there’s no way to persistently change the population.

Peter and Rosemary grant caught many finches, enough to understand the distribution of beak depths in the entire population on a small island, Daphne Major. In 1977, however, there was a severe drought on Daphne Major. With less water, many plants were less able to make seeds and the drought differentially impacted which seeds were available. Small seeds were harder to find, but big seeds from plants that were more drought-tolerant were abundant. Birds with larger beaks were better able to break the big seeds, and so birds with larger beaks acquired more food and had more babies than birds with smaller beaks.

Below, Peter & Rosemary show the shift in the distribution of beak sizes between the parents prior to the 1977 drought and offspring following the 1977 drought. If you had M&M’s equally sampled among the colors, then you would get a next generation that has a similar distribution of colors as the previous generation. If, however, you disproportionately sample green M&M’s, then the next generation is likely to have more green M&M’s than the parents. This is an inescapable, mathematical fact that underlies modern evolutionary theory: if we have reproduction with heritable variation and differential fitness, we get evolution. Peter & Rosemary showed both heritable variation and, below, differential fitness, with the mathematical consequence of evolution or changes in the frequencies of traits in a population.

The Axioms of Evolution

Darwin and the Grants have done wonders to illuminate the empirical signatures of evolution and the mathematical structure of evolution has been fleshed out by others. One of the best and simplest run-downs of the mathematics of evolution comes from a gentleman named Richard Lewontin in his classic article The Units of Selection. Lewontin breaks down Darwin’s theory to three principles:

Phenotypic variation (e.g. different beak sizes across birds)

Differential fitness (different numbers of offspring across birds)

Heritable variation in fitness

If you have these three principles, then, mathematically, the population will change over time. If the drought persisted, then birds with bigger beaks in 1978 would also have differential fitness, they would disproportionately be offspring of birds with bigger beaks in 1977, and the variation in fitness from the 1977 drought would persist to the subsequent drought. Evolution would continue.

These axioms define a useful mathematical architecture for thinking about evolution. There are other useful mathematical tools, such as the Wright-Fisher process for studying how a population changes from one generation to the next to “adaptive dynamics” and “evolutionary game theory” for studying how payoffs from ecological interactions affect the community composition and dynamics (“ecological interactions” can be competition between males who may fight to the death, or parasite/host dynamics, how slime molds make the decision to form spore capsules, and more).

In this sense, evolution, sensu stricto the changes in frequencies of traits over time, is a rather trivial mathematical consequence of axioms. Empirically, we find that those axioms clearly hold in nature today and we have no reason to assume they didn’t hold in the past, especially when we examine other evidence on the age of the Earth, the fossil record and its consilience with methods for dating rocks, and more. The mathematical and empirical foundations of evolutionary theory tell us how variation in traits can combine with differential fitness to push populations in some direction but, strictly speaking, it doesn’t tell us where this variation comes from.

Where did big and small-beaked birds come from in the first place? To understand the process of mutation and innovation generating new traits, we have to zoom inside the cells to understand the biochemical determinants of traits.

The central dogma and heritability

Yet again in my writings, it’s important to revisit the most important molecular biological insight that underpins modern biology. We call this “The Central Dogma” of molecular biology although I and others think the word “dogma” is a bit, well, dogmatic. Rather than call it a dogma, I’ll call it a set of well-established facts regarding what tends to happen in nature. These facts tell us how instructions in DNA are converted into a trait like the size of a beak or the color of a lizard.

Big picture, DNA is transcribed to RNA, RNA is translated into proteins, and proteins define traits. The replication of DNA is error-prone and with the genetic code we can see how mutations in DNA can generate novel traits by changing proteins. If you already know this, feel free to skip this section!

DNA—>RNA Transcription

DNA is a chain of molecules called ‘nucleic acids’. There are four ‘nucleotides’ in DNA (A, T, G, C) that can link up in a long chain and each one can additionally bind to a complementary nucleotide (A-T, G-C). When we sequence DNA, we record the sequence of nucleotides in a strand but, in the cell, DNA is double-stranded in an often knotted/balled-up double-helix. In other words, we sequence one strand, and by the complementary binding of nucleotides we automatically get the other strand’s sequence (were it not for complementary binding, one could imagine more complex designs of knotted non-complementary strands requiring we sequence both sides).

Below, I randomly typed the top strand, and the bottom strand is what we would observe if we sequenced the complementary strand.

5’ - ATCGCTACT - 3’

3’ - TAGCGATGA - 5’

The 5’ (five-prime) and 3’ (three-prime) indications tell us the directionality of the strand. If you look at nucleotides, they’re not symmetric (like a Lego block) and so the chain of nucleotides has different chemical attachment points on either side. When we grow strands of DNA, we “polymerize” or connect the nucleotides from the 5’—>3’ direction. As you can interpret information typed on this page if you read this English from left to right, you can find the information contained in DNA by reading it 5’ to 3’.

DNA is like a book in a library containing instructions for how to make a machine (the protein). However, one can get a childhood intuition of the central dogma by imagining that we can’t make machines in the library, we have to make machines in the factory, and the library doesn’t like to lend out its books. How do we get information from the library to the factory? We take photocopies of pages with blueprints for the machine and take the photocopies to the factory to make the machine. DNA is the book of blueprints in a quiet library (the nucleus), RNA is the photocopy of DNA sent to the factory (the cytoplasm or the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum, two factories in the cell), and these photocopies are used to build machines - proteins.RNA—>Protein Translation

RNA is also a chain of nucleic acids, but, when used as a messenger/photocopy to make proteins, the RNA is typically a single strand. A single strand of RNA has all those nucleotides exposed to the elements, each of them with particular positive and negative charges, and it is very fragile.

If you were to hold the RNA in your hand, I imagine it would feel like a wispy, flimsy magnetic tape drawn towards a complementary strand of magnetic tape, including complementary strands down-stream on the same piece of tape, so much like tape if you don’t take care to stretch out this mRNA in your hand it will fold up and bind to itself. Below is an example of an RNA molecules fold up on itself (yup, biology and math geeks have already named all those knots & twists that you get when tape binds to itself)!

If you held a single-stranded mRNA molecule in your hand, it would feel like a flimsy piece of magnetic tape that binds to itself, forming all sorts of frustrating stems, loops and stacks. Fear not, sometimes the function of RNA is made possible thanks to these self-bound-sticky-tape secondary structures!

Floating around in the cell is another molecule called “tRNA” where the t stands for “transfer”. tRNA is also an RNA molecule, but it’s not the messenger. Rather, tRNA is like a converter cable of the cell, but instead of converting from VGA to HDMI or an electrical socket to a USB, tRNA converts triplets of nucleotides called ‘codons’ (e.g. ATA or AUG or CGG) to amino acids. Where RNA has the triplet CGG, the complementary tRNA GCC can bind

tRNA: 3’ - GCC - 5’

mRNA: 5’ - CGG - 3’

and any tRNA with 3’ - GCC - 5’ will have a very specific amino acid attached to it: Arginine. There are 4 nucleotides that can exist in each of the 3 spots in a codon, producing 4^3 = 64 possible codons. There’s a tRNA for every single one of the 64 possible codons, and every tRNA converts its codon to an amino acid. Remember holding that sticky-tape of RNA in your hand? Well, tRNA is RNA that binds on itself, and so it has an exposed codon along with a bunch of other stems and secondary structures that help it convert the information from a codon into the appropriate amino acid!The Genetic Code:

There are 20 different amino acids that vary in their charge and other side-chains that affect what they bind to and how they behave chemically, and the tRNA transfers information from this sequence of nucleic acids in RNA (photocopied from DNA) to a sequence of amino acids. Above is an image drawn from here of “messenger” RNA, tRNA, and the amino acid Met or methionine. The genetic code is an empirical look-up table that we observe across all of life, it is the mapping between codons in RNA and amino acids. The common genetic code is part of the reason we believe all living things today are derived from a common ancestor, because if life originated several times independently then it seems unlikely that they would independently evolve this same mapping between 64 codons and 20 amino acids.

So, to recap, there’s this “central dogma” of molecular biology that rests on a set of well-established facts. DNA is transcribed into RNA and RNA is translated into sequences of amino acids, those sequences of amino acids become proteins that do the biochemical stuff that makes life what it is. We’re all bags of bitchy, demanding enzymes, and the central dogma tells us how those enzymes are made.

We don’t inherit proteins from our parents, we inherit DNA. DNA provides instructions for how to make proteins, and those instructions are carried out by a few well-understood steps. Consider, for example, my red hair, my freckles, and the colors of my old family cockatiel’s feathers:

My red hair is made of the protein, keratin, and it is colored by a bunch of other non-protein compounds called melanins. While melanins are not proteins, their production - a process called melanogensis - is regulated by enzymes which are proteins. The exact processes regulating the production of melanins are not understood by me at this time (that would require a deep-dive and, I believe, it’s not fully understood by scientists as well, so science goes on!). However, the big picture is that even complex metabolites like melanins are made by proteins and/or have their concentrations in tissues regulated by proteins. Our hair colors - and the pigmentation of birds whose colors attract mates or bearded dragons who attract breeders artificially selecting color morphs - are heritable because they are made up of proteins and/or regulated in some way by proteins, all of which are encoded by the DNA that we received from our ancestors.

Proteins Define Traits

Let’s get more cozy with some proteins. Here’s a snapshot of a protein you know and love that is roaming your veins as we speak: hemoglobin,

Here’s another protein you know: insulin

I get it, these weird squiggles aren’t the same as smiley faces. Hard to cozy up to these things. Scientists represent proteins a few different ways, but above is a common view of proteins that contains a lot of information. The sequence of amino acids sometimes bundles up into spirals that you see clearly indicated as positively charged amino acids get close to negatively charged ones. In other places, the sequences of amino acids form sheets. This massive, messy bundle of amino acids has substructures like “alpha-helices” (spirals), “beta-sheets”, “active sites” that bind substrates and catalyze chemical reactions, and more. The entire protein has its own larger chemical properties that are the direct consequence of the sequence of amino acids and how they ball & twist up. The particular mess of folds in hemoglobin helps it bind oxygen and CO2, enabling hemoglobin to exchange gas at our lungs and throughout the blood stream, trading CO2 for O2 at the lungs and trading O2 for CO2 near those cells that have burned sugars and made CO2.

Proteins are not static, brick-like, frozen objects like those show in in the pictures above. Even atoms that proteins are made up of have fuzzy clouds of electrons whizzing about the nucleus, and that cloud of negative charge created by the electrons can bulge towards an exposed positive charge here or bulge away from an exposed negative charge there. If you were the size of a protein and you hugged it, you could feel those fuzzy, charged electron clouds. You’d be in a crowded cytoplasm or other environment with myriad other chemicals with varying charges whirring about, bumping into you and causing the electron clouds of the protein to bulge, causing the spirals, sheets, and strings in the protein knot to bend and twist and change their conformations.

Proteins wobble constantly, and how they wobble changes depending on the chemical environment they’re in. Where there’s a lot of CO2 in the blood, hemoglobin wobbles to a shape that is less able to bind O2 and better able to bind CO2. So, where there’s a lot of CO2 in the blood, such as in your legs that burn sugars as you run, hemoglobin will wobble to a different conformation, deposit the oxygen its brought from the lungs, and grab CO2 to ship it to the lungs. At the lungs, there’s less CO2 in the blood and so hemoglobin wobbles back to a shape that’s better able to bind O2, causing it to drop off the CO2 in your lungs and pick up O2. The wiggles and wobbles and conformational changes of proteins can be essential to their functions.

Big picture: proteins are big, wiggly, wobbly chains of amino acids that perform functions. If you change the sequence of DNA you can change the function of the protein by changing its shape and possibly how it wiggles and wobbles in different chemical environments. If you change the function of the protein, you can affect the fitness of the organism as a whole. If a mutation in DNA changes the function of the protein to increase the fitness of the organism, then that mutation will increase in frequency in the population.

We can thus study evolution of entire organisms by thinking about the proteins, and we can study the proteins by studying the DNA.

Tibetans, for example, appear to have evolved to the high altitudes of the Tibetan Plateau where the air is thin. If you sequence the DNA of Tibetans, you’ll find mutations in the Tibetan genome that separate them from closely related Han Chinese genomes. Many of those mutations that distinguish the Tibetan genome from closely related genomes in lower elevations occur in genes that encode proteins related to gas exchange. The mutations don’t need to be in hemoglobin, exactly, but they can be in proteins that regulate the production of hemoglobin. In other organisms, such as birds that live at high elevations in the Andes, sometimes it is hemoglobin that is mutated directly, helping the organisms live at higher elevations.

As with the complex trait “gas exchange”, the same thinking applies to other complex traits affected by many proteins. The size of bird beaks, for example, is probably not encoded by a single protein. There’s no protein that is your ‘size’ protein. Rather, many size-related traits, including the traits determining the size differences between a Chihuahua and a Great Dane, trace back to proteins that regulate embryonic development and downstream development after birth.

How do we go from a single cell to a massive organism, from a bearded dragon to a blue whale? When we were tiny bundles of cells in the placenta, or when my lizards were tiny bundles of cells inside their eggs, we played a coordinated symphony of symphonies called embryonic development in which cells divided in synchrony and a beautiful music of signaling molecules kept the tempo and guided cells with their transitions to different tissue types. As a symphony without coordination or conduction results in noise, embryonic development with cells that are selfish and uncoordinated would result in randomly grotesque, misshapen, and disproportionate bags of cells, not the beautiful, well-organized, symmetric and thriving organisms we are today.

During this symphony of symphonies, it’s proteins that make signaling molecules, proteins that receive them, proteins that process the signals into instructions for the cells that are dividing, and proteins that divide the cells. Mutations in these proteins that guide embryonic development can have major impacts on the resulting organism. After birth, there’s less room to modify the organism but mutations in the proteins regulating signaling molecules like hormones or steroids can affect our development further.

The heritability of bird beak size probably traces to some subtle mutations in the DNA encoding proteins that regulate cell division during embryonic development and beyond. I’ll go ahead and wager this without actually knowing the right answer or googling it (such is the fun of science, where we call our wagers ‘hypotheses’), so feel free to test my hypothesis and share what you find! The big picture here is that persistently heritable traits are almost always due to heritable mutations in DNA that encode proteins that affect the trait. The trait can be something as large and complex as the body size of a blue whale, possibly regulated by proteins involved in cell signaling or embryonic development, to something as small as keratin and the proteins regulating the production of melanin in a single strand of hair.

Proteins and enzymes evolve through mutations in DNA, and the process by which DNA mutates is also well known. The complex systems that govern the development of large organisms can be highly sensitive to tiny mutations, especially when tiny mutations occur in regulatory genes, and billions of years of evolution has produced organisms that are stable platforms for further modification and evolution. Humans were able to utilize the stability of these “biological platforms” to breed wolves into everything from Chihuahuas to Great Danes without knowing the specific genes governing the size of the dog, but by exploiting the underlying processes of mutation and heritability of traits, imposing persistent differential fitness, and slightly changing the tempo of that symphony of symphonies in embryonic development to make wolves bigger or smaller, fluffier and cuter. This same artificial selection made cows, sheep, horses, corn, beans, and more. Natural selection works the same way, except fitness differentials are imposed by nature and not the aesthetics of humans.

With the central dogma, the mathematics of evolution, and a knowledge of how organisms grow from single cells with DNA to vast metabolic networks and multicellular organisms, we have a clear and consilient explanation for evolution of life through a series of well-established facts about how DNA encodes proteins, how proteins drive traits, how traits determine fitness, how fitness affects reproduction, and how DNA replicates imperfectly during reproduction. There are even some instances in which we’ve observed evolutionary novelties in recent human history, such as the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacteria.

The Origin of Antibiotic Resistance

I thought I had a good handle on evolution with all my lizard breeding and Chuck Darwin reading. Little did I know, there were more beautiful stories out there waiting to be learned.

I spent a summer in college working with Gregory Petsko and Dagmar Ringe at Brandeis University. Greg and Dagmar are protein biochemists; they study the chemical reactions behind the structure and function of proteins. Greg, a die-hard lover of Greek philosophy, heard about my fascination with evolution and my history breeding lizards and pursued a Socratic line of inquiry to inspire his pupil.

“So, lizards can be different colors. What determines the color of lizards?” Greg asked.

“Pigments in their skin?” I hypothesized.

“That’s right. And what makes the pigments in the skin?” Greg inquired.

“Enzymes?” I guessed.

“I bet so,” said Greg, “just like photosynthesis, the Kreb’s cycle, or even the breakdown of antibiotics by antibiotic resistant bacteria, I’ll bet the catalytic underpinnings of the trait can be traced to an enzyme.

”Now, have we always had these pigments? Similar question: have living things always photosynthesized? If not, then where did the ability to make a pigment evolve from? Where do novel catalytic functions come from?”

My eyes slowly widened as I caught on. With just a few questions, Dr. Petsko unlocked the door to a whole world of evolutionary biochemical revelations.

Evolution tends to draw on pre-existing structures and modify them slightly, imperfectly, with selection to improve their function for a novel task that is suddenly very important for the organism. Snakes have hip bones because snakes weren’t designed from scratch but rather evolved from a common ancestor with lizards with heritable variation and differential fitness for serpentine motion. Whales have lungs and not gills because whales evolved from Tetrapods that evolved lungs to live on land and it seems quite hard to evolve gills from scratch once an organism has lungs. So, instead of gills, the evolution of whales repurposed their nose into something of a snorkel, creating blowholes. Tomorrow’s organisms and traits come from natural selection repurposing today’s organisms and their traits.

Assisting a very specific chemical reaction, as enzymes do, is no easy task. To catalyze a chemical reaction, our giant, wiggly, wobbly machines encoded by DNA need to hold tiny molecules in the palm of their active sites and fuse them together at exactly the right angle and energy otherwise they risk either wasting time and energy, or creating a molecular monstrosity that can damage our cells. It is unlikely that a random sequence of DNA translated into a random sequence of amino acids will be able to perform the molecular surgery of a highly specific catalysis. Instead, novel enzymatic functions probably come from repurposing pre-existing enzymes that perform similar catalytic functions and can be mutated to enhance that novel function. Today’s proteins are enzymatic blowholes or proteinaceous snake-hipbones repurposed from yesterday’s enzymes and proteins.

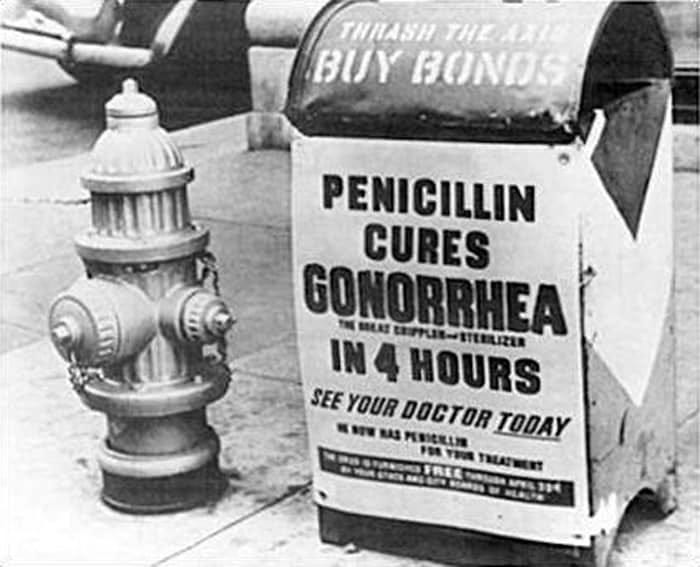

Greg and Dagmar pointed me towards a special set of enzymes to study: Beta-lactamases. You know these enzymes, too (kinda like how you know a person even if you forgot their name - to paraphrase Richard Feynman, there’s a difference between knowing the name of a thing and knowing the thing; in biology, focus on knowing and intuiting the thing and then you can memorize the name for a test :-D). You know about the “beta-lactam” things already. Penicillin is part of the family of antibiotics called “Beta-Lactams”. “Beta-lactamases” are enzymes that break down these beta-lactams. Below is a picture of the chemical structure of penicillin. If you don’t know how to read this, don’t worry at all. Look at the lines & letters and imagine making a stick model of that chemical structure with toothpicks, olives (O), putty, grapes (N), etc. Make a 3D version of this in your head where the solid wedge up to NH comes towards you and the dashed lines to H or that O=-OH go away from you.

Do you see the square in the middle of penicillin? That square with an N(itrogen) and then two lines going below & left to the O(xygen) is very special. Penicillin works when that square latches onto a bacterial protein like a monkey wrench, stopping the protein from doing its enzymatic job of helping the bacteria synthesize its cell wall. There are other beta-lactamases like ampicillin, amoxicillin, and more - they all have that square and so they all function the same way as Penicillin. To stop penicillin or other beta-lactams from killing bacteria, beta-lactamase enzymes break that square before it can bind like a monkey wrench to the bacterial protein targe. To break that square, Beta-lactamases essentially shove a water molecule (H20) at the square and break it with a chemical reaction called “hydrolysis”. “Hydro-lysis” = “water-breaking”.

Penicillin was first mass-produced in 1943 and immediately became used all around the world. Bacteria that normally colonized humans with relative impunity to cause disease were suddenly bombarded with a molecule that stopped the synthesis of the cell wall and killed bacteria. Bacterial infections would still happen, but they became treatable and that treatment wiped out entire islands of bacteria inside human hosts.

Humans were winning the battle with bacteria until suddenly, in 1947, scientists documented bacteria that were resistant to penicillin. The molecular bullets we were firing at bacteria appeared to dissolve in mid-air before they ever impacted the cell wall. The molecular magic of bacterial missile-defense systems was made possible by, among other proteinaceous tricks, the beta-lactamases. How did this new enzymatic activity evolve?

If you look at the DNA sequence of beta-lactamases and scan the genomes of bacteria to look for similar sequences, we find many enzymes that are related to Beta-lactamases but are so many mutations removed that they must have existed before Penicillin was mass-produced. By building the evolutionary tree of beta-lactamases, we can study the evolution of novel enzymatic functions like the hydrolysis of penicillin.

Researchers learned that the distant cousins of beta-lactamases break down compounds called “lactones” with a similar hydrolysis reaction, but for a completely different ecological reason. Bacteria hydrolyze lactones to detect how many other bacteria are in the surrounding area thereby allowing them to change their behavior if there are enough bacteria present, a phenomenon called “quorum sensing”. If a quorum of bacteria are also present on the skin, bacteria can coordinate their metabolic strategies to act as a swarm, causing zits and other manners of microbial mishief.

Below is a lactone called “acyl homoserine lactone”. Bacteria make molecules like these (with enzymes!) and secrete these molecules as signaling molecules to tell other bacteria that they are present. When enough bacteria are present, the microbial revolution begins!

Do you see that pentagon on the left side of the lactone? In order to detect how many bacteria are present, bacteria secrete lactonases - the cousins of the enzymes that break down penicillin - and lactonases break that pentagon. Want to guess how lactonases work their magic? They shove a water molecule at that intersection between the O in the ring and the O with two lines coming out of it. That sub-structure is called an “ester” and the chemical reaction that bacteria use to break this ring is called “ester hydrolysis”.

In just four years, bacteria evolved the ability to break down penicillin with a new enzyme that shoved a water molecule into a four-membered ring to “hydrolyze a cyclic amide”. The cousins of these novel enzymes “hydrolyze a cyclic ester” by shoving a water molecule into a five-membered ring. As bats evolved wings from flaps of skin between their bones, as whales evolved blowholes from their noses, and as birds evolved wings from feathers on their arms, the novel enzymes that bacteria use to break down Penicillin appear to be evolutionarily repurposed from pre-existing enzymes that performed a similar catalytic function.

Even Enzymes Evolve

Greg Petsko and Dagmar Ringe have fleshed out the details of enzyme evolution by focusing on the specific sub-structures of enzymes that change and affect the catalytic function of the enzyme. This enzymatic view of evolution helps us make new proteins, understand the evolution of gas exchange in Tibetans, and annotate biological databases and by ascribing hypothesized functions (e.g. hydrolysis) to enzymes that we’ve never studied before in the lab but which are closely related to enzymes of a known function. Greg, a prolific and extremely entertaining writer who also ridiculed the word “dogma” in our biology textbooks, ultimately wrote with Dagmar and other colleagues one of my favorite articles of all time: “On the Origin of Enzymatic Species”.

While far less intuitive to the lay audience than the evolution of beak sizes in birds, body sizes in dogs, or color morphs in bearded dragons, the evolution of enzymes occurs through similar mechanisms. DNA is mutated through error-prone replication, those mutations change the sequence of amino acids, those amino acids bundle up into a slightly different protein ball, and that protein behaves slightly differently than proteins without the mutations. If the new protein behaves ‘better’ in the sense that it helps the organism have more babies than organisms without these mutations, then in the next generation there will be a higher frequency of organisms with these mutations than there were in the previous generation.

Bacteria already had an enzyme that could grab onto a five-member ring and hydrolyze it, chances are that wiggly, wobbly protein could also latch onto the historic four-member ring and hydrolyze it, too. A few mutations and the wiggly, wobbly protein was even better at breaking down penicillin, and eventually a bacterial missile defense system was deployed and antimicrobial resistance evolved before our eyes.

When you breathe in oxygen, your body has hemoglobin rushing to the scene to bind it and shuttle it to the periphery. Hemoglobin evolved. Prior to 2.4 billion years ago, there was no need for organisms to have hemoglobin because there was no oxygen in the atmosphere. All that changed when oxygenic photosynthesis evolved. Oxygenic photosynthesis is made possible by the molecule that makes plants green - chlorophyll. Chlorophyll is synthesized by enzymes before being bound to proteins, hence chlorophyll wasn’t a molecular accident one organism stumbled upon and consumed, but rather it became encoded as a heritable trait in the DNA of plants. Novel catalytic functions like photosynthesis that make our lives possible originated through a similar series of steps in enzyme evolution, whereby mutations beget new functions and the repurposing of proteins leads to entirely new pathways.

Novel enzymatic pathways create new molecules that in turn select for novel enzymatic functions, as the production of chlorophyll selected for enzymes that utilize oxygen and so on. Life doesn’t just evolve, it co-evolves. Fungi evolve to produce penicillin, humans socially evolve to mass-produce this compound, bacteria evolve to defend themselves against penicillin, humans modify their antibiotics to overcome bacterial defenses, and so on to infinity it seems. The evolutionary dance between predators and prey has created large, fast, and skittish prey (with enzymes regulating their body size, muscle fibers, and brain chemistry) as surely as it has created fast, sneaky, and strong predators. The evolutionary dance between pathogens and hosts has created host defenses such as toll-like receptors (proteins), T-cell receptors (proteins), antibodies (proteins), and more. As hosts evolve defenses, pathogens evolve tools to evade them, including VP35, an enzyme in ebola that turns off the protein alarm bells in mammalian cells, or mutations in the Spike gene of SARS-CoV-2 that evade antibodies that target the ancestral lineage or the vaccine.

Such is the modern view, and remarkable scientific power, of evolutionary biology.

Contemporary evolutionary biology rests on a series of indisputable facts - DNA replicates imperfectly, DNA encodes proteins, and proteins define traits - and other mathematical consequences of simple axioms like those Lewontin proposed. If there is heritable variation and differential fitness, then there will be changes in the frequencies of things. In the next generation, imperfect DNA replication modifies proteins further and has the possibility of enhancing traits that conferred higher fitness. All traits, however complex, trace back to enzymes whose evolutionary arcs trace back to the mutations in DNA which occurs by well-understood and well-documented molecular accidents. Emerging from these simple molecular processes is an entire world full of organisms evolving and co-evolving in a great biological race.

Without knowing about the theory of evolution, humans have nonetheless been able to utilize it to breed wolves into Great Danes and Irish Wolfhounds, huskies and German shepherds, Chihuahuas and Dachshunds, and more. We’ve bred cows into docile vats cranking out high volumes of milk. We’ve bred corn from a short grass to a towering factory with massive husks and enlarged kernels. Without knowing it, we triggered the evolution of antimicrobial resistance when we rained antimicrobial fire on bacteria, as those bacteria repurposed an enzyme to perform a nominally similar catalytic function - hydrolysis of a cyclic amide or ester - with a vastly different ecological purpose. The remarkable creativity of evolution comes from the pre-existing diversity of life and the inevitable no-holds-barred approach by which mutations can repurpose pre-existing forms to adapt to new circumstances, such as mutating a quorum sensing enzyme into an antimicrobial missile defense system (and that is just one of the many microbial defense systems that has evolved since we discovered antibiotics).

Now, in the 21st century as sequencing costs drop and sequencing capacity skyrockets, we’re in a position of being able to read the genomes of organisms and learn the story of these mutations. We have databases with millions of whole-genomes whose differences tell a story of both random mutation and natural or artificial selection. Darwin did not know about DNA at the time of his writing, nor did Mendel know of genes and proteins when breeding plants. Lewontin wrote his axioms before we had ever sequenced the human genome. When I was a kid breeding lizards, the human genome project was just beginning; we didn’t know the genomes of bearded dragons, Darwin’s finches, or dogs. As we’ve learned more about the molecular biology, the theory of evolution has been corroborated by every single one of the millions of genomes we’ve collected, from contemporary humans to the genomes of extinct mastodons, and our understanding of the history of life has become richer and more firmly grounded in this vast network of observations.

Bioengineering Makes Evolutionary Anomalies

We use this theory and the underlying mathematical & statistical principles not only to understand the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in humans, but to study the evolution of SARS coronaviruses before humans. We use the genomes of bat SARS coronaviruses we’ve collected to understand the evolution of proteins like the Spike protein and its little motifs like the furin cleavage site. By counting differences, whether single nucleotide changes or large insertions of functional motifs, and estimating the time elapsed, we can estimate the rates of mutations. The methods we use to estimate evolutionary rates provide molecular clocks to estimate the timing of common ancestors and rates of insertions of furin cleavage sites in sarbecoviruses. These methods are calibrated and built upon a vast literature quantifying the rates of evolution in populations from finches and lizards to E. coli, HIV, and influenza.

The mathematics and statistics of evolution lurked behind our analyses of the restriction map of SARS-CoV-2. Valentin and Tony noticed the pattern as something glaringly non-natural just you notice a heart carved on a tree as something different from the natural bark and texture of the tree. Turning their observation into a robust paper required we quantify the odds of that weird pattern occurring in nature.

To do so, we drew on the evolution of SARS CoVs and the ecology of restriction enzymes. Restriction enzymes are bacterial defense systems that cleave viral genetic material that happens to ender the bacterial cell. As a consequence, restriction enzymes are typically found inside the cytoplasm of bacteria. Coronaviruses, meanwhile, infect mammalian cells and therefore restriction enzymes locked inside a bacterial cell are unlikely to ever encounter & cleave a wild coronavirus. The absence of restriction enzymes in the history of coronaviruses evolution led us to conjecture there shouldn’t be any selection for even-spacing or anomalously short maximum fragment lengths in the genome of SARS-CoV-2, and so the sites in the genome recognized by restriction enzymes should be randomly spaced.

Additionally, we used our knowledge of bioengineering to develop additional tests of the mutations to the genetic code that generated these sites. Some mutations in DNA change the amino acids, others - called “silent” or synonymous mutations - don’t, and so if these restriction sites were truly randomly scattered about the genome of SARS-CoV-2, and we got lucky in finding sites that happened to have an unusual pattern, then under a natural origin of SARS-CoV-2 we should expect to see a similar rate of silent mutations inside these randomly-scattered sites and outside these sites in the rest of the viral genome.

On the other hand, bioengineers also know about silent mutations. When virologists mutate a virus to make a reverse genetics system for study in a lab, they want the viral proteins in the lab to have the same amino acids as the viral proteins in the wild, otherwise the proteins in the lab wiggle & wobble in different ways and the researchers won’t know if the traits they measure are traits of a wild virus or traits unique to their modified laboratory construct. To preserve the protein functions in the design of a reverse genetics system, virologists use exclusively silent mutations. Under a laboratory origin, then, we hypothesized that there would be a higher concentration of silent mutations inside these unusually-spaced restriction sites than in the rest of the genome.

SARS-CoV-2 has a furin cleavage site not found in 1,000 years of sarbecovirus evolution. We have looked hard for furin cleavage sites in sarbecoviruses, but the only thing we find is a 2018 grant proposing to insert a furin cleavage site in a bat SARS CoV reverse genetics system in Wuhan. We found the Bsal/BsmBl restriction map of SARS-CoV-2 is consistent with a reverse genetics system, every mutation within these enzymes’ recognition sites was silent, and there were 8-9x higher rates of silent mutations within these sites than the rest of the genome.

Evolutionary theory can help ground our statistics and reasoning when studying not only the origins of species or the origins of enzymes, but also the origins of viruses. As a kid I bemoaned the inability to conjure crocodiles from my bearded dragon eggs, but it is the regularity and predictability of ecology and evolution that allows us to classify bioengineered organisms as such and attribute SARS-CoV-2 to a lab.

I just ADORE your articles.

I love the way you write about biology and science. I suspect you would be a wonderful teacher of both adults and children. You combine your obvious technical knowledge with wonder and reverence for everything around us, in an uncontrived and extremely sensitive manner. This is not easy to do! Thank you for your writing. I look forward to your posts and so await the next. 🙏🏽