Finding a Ruby in the Rubbish

In the early days of 2020, I was a mere postdoc at Montana State University. In the hierarchical eyes of the academy, I was nothing, nobody, not worth the time of day.

I don’t believe that narrative about myself, but one becomes self-aware of their place in a totem pole when cold-calling professors with my Montana State email address. My personal narrative is one of curiosity, academic success, a PhD at Princeton, a postdoc at Duke University where I did amazing science despite my postdoc advisor passing away. To help pay for my wife’s medical bills, I started a consulting business on the side, doing biostatistics by day and hedge fund trading strategy development by night. We chose Montana because I’m not in it for fame or fortune… and my wife likes to ski, so I took a job researching pathogen spillover & outbreak forecasting in Montana a few years before bat viruses became cool.

When forecasting skills from my financial side-hustle brought new findings to light on COVID-19 outbreaks and the epidemiology of this new bat SARS-related coronavirus, I felt an obligation to share my findings. I didn’t want my medical intelligence insights to just make the rich richer, I wanted to help everyone navigate the pandemic ahead of us with the best available information my information sciences could provide.

My findings were simple, hidden in plain sight: the early outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 was faster growing than many epidemiologists estimated. One thing we don’t screw around with in finance is estimating exponential growth rates - that’s how you estimate returns, and returns are the bread & butter of finance. According to my estimates, case growth rates were much faster than all the conventional models estimated at the time, and faster growth rates with the same start date implied more cases, a larger subclinical iceberg of infections, lower odds of successful containment, and lower severity. With faster growth rates, estimates of the severity of the pandemic become extremely sensitive to the start date; 2-day doubling time starting 20 days ago will generate 1,000 infections, but 2-day doubling times starting 60 days ago will generate 1 billion infections. Every 2-days we err in our highly uncertain estimate of start-dates, our estimate of pandemic size and burden changes by 2x.

I shared a write-up on these findings privately and most people saw rubbish. One professor from Oxford even said directly to me that if Harvard is saying one thing and Alex from Bozeman is saying another, he will believe what Harvard says. As I tried to warn people of an oncoming bullet train of a pandemic in February 2020, I received stern emails from distinguished professors high up the totem pole claiming that if I shared my findings openly, it could sow complacency and “disrupt the public health message”.

In emergency situations, I’m accustomed to flattening hierarchies, trusting information as sincere and ensuring communication flows. In the early days of COVID, however, our information was not shared widely, the tall totem pole of academic hierarchy did not flatten, and my statistics were assumed to be rubbish.

Jay Bhattacharya, meanwhile, found the ruby.

Fast forward past the plot of COVID-19, the warzone of science and politics, past the efforts of the former NIH director to censor Jay, past a pandemic that traumatized the world and left our civil discourse in disarray, and we arrive at the world today in which Jay has been nominated as director of NIH.

You will hear many things said about Jay, many predictable hot takes from people whose views you already know based on their attitudes and beliefs during the pandemic. You’ll find the same people who told me not to share my findings, the same people who favored censorship of scientists, saying that nominating Jay is a terrible thing, and you’ll find the extremely large and diverse group of scientists, doctors, and managers who found Jay eminently reasonable coming to his defense.

What’s missing from the partisan discourse is nuance and compassion, curiosity and understanding. In a way, our political discourse is a macrocosm and scientific discourse a microcosm of our tribal polarization, and the same knee-jerk reactions that led people to assume my findings were wrong and sharing my information irresponsible are now leading people to assume the closest, fastest, most tribally aligned view on the incoming president’s nominees.

What I hope to add to our civic mosh pit is a calm view of a scientific journey through COVID that led reasonable people of many political stripes to abandon tribes for truth. This journey is a tapestry of scientific evidence, uncertainty, sincere questions of the ethical responsibilities of scientists and medical doctors, and this tapestry is held together by two virtues that Dr. Jay Bhattacharya has demonstrated throughout these tempestuous times: curiosity and grace.

Instead of narratives or hot takes, I with to show the world something I’ve been lucky to behold in my unique journey, something we need: The Grace of Dr. Jay.

Early Outbreak Epidemiology and Forecasting

Now, rewind back to February 2020. I had information of fast-growing cases, my academic superiors were reluctant to review it and discouraged me from sharing it.

The findings of fast growth rate I observed were also observed (in a very different way) by Jay’s Stanford colleague and Nobel Laurette Michael Levitt. Another Stanford colleague, John Ioannidis, was also plugged into this stream of information and cautioned that significant public health policy decisions were being made despite massive uncertainty.

From this starting observation of fast growth, a cluster of scientists aware our massive uncertainty went forward attempting to collect more evidence.

Sunetra Gupta, PI on a paper led by Jose Lourenco, revealed the enormous range of our uncertainty using the UK outbreak as a case study. Lourenco et al. underscored that forecasts were highly sensitive to an unknown start date, and they called for serosurveys to calibrate our models & forecasts.

I assembled a team of colleagues to see if the forecasts of faster growth were true & resulted in earlier-than-expected outbreaks in the US. By the third week of March, 2020, we saw an enormous excess of patients visiting outpatient providers with influenza-like illness (ILI). We used the excess in ILI to estimate the number of people who may have COVID by March 2020. Our paper led to an article in The Economist: “Why a Study Showing COVID-19 is Everywhere is Good News”, and we stayed open to public feedback, ultimately hearing one critical piece of feedback that altered our estimate (science!!!). Our updated estimate was that as many as 9 million people had COVID by March 28, 2020, and 9 million infections implied an infection fatality rate of around 0.3%. Together, these estimates suggested an unmitigated US outbreak could see cases peak around 1-2 deaths per 1,000 capita.

At the time of our ILI odyssey, Justin, Nathaniel and I were in communication with the NY State COVID task force, helping them establish dashboards to monitor the situation as they relaxed interventions and discussing the evidence base for various public health policies. While I wasn’t able to share the fast-growth evidence in time to warn the public of a pandemic, I committed to sharing later evidence and doing so provided valuable resources to managers struggling to deal with the uncertainty. “The public health message” that I was warned about was monolithic, but the reality of uncertainty is that there are many possibilities, and in times of uncertainty managers are better served by hearing the full range of possibilities.

The counter-argument was that scientists needed to scare the public, to err on the side of overestimating pandemic severity because of asymmetric costs and because of the behavioral consequences of underestimation (sowing complacency & causing deaths). This ethical conundrum is one for everyone to consider: if you are a manager or a member of the public, and scientists find something consequential yet uncertain, would you rather they overestimate the risks, or would you rather they popularize the full range of possibilities so you can make your own decision?

Meanwhile, Jay, John Ioannidis, and colleagues also sought to resolve our uncertainty with more empirical evidence. Jay et al. courageously conducted a serosurvey in Santa Clara county, California. Their serosurvey estimated a 1.2% prevalence of COVID-19 exposures in Santa Clara county, consistent with the general thesis of COVID outbreaks being characterized by earlier-than-expected introductions, fast growth, and a large subclinical iceberg of cases implying a lower pandemic severity.

Critiques of Lower-Severity Estimates

When our ILI paper published, many people abandoned the notion that I was some rubbish postdoc and started criticizing me like I was a rubbish tenured professor. There were sharp words about me undermining “the public health message” without pointing to what, exactly, “the message” was and who was able to decide it. None of our critics were in the room with the NY State COVID task force during the worst outbreak surge on US soils since 1918. In this sense, by working directly with managers as they sought to handle a terrifying situation, we were a bit closer to the public health policy process/chaos than most and we would’ve shared our insights and nuanced thoughts if there was space to do so. By estimating too many cases, we - not the data nor the statistical methods we used - were critiqued as “minimizing” the severity of the pandemic, sowing complacency, and ultimately such minimization could cause deaths.

However, our estimates were not minima, they were midpoints, averages and medians. Midpoint estimates from the data are not minimizations, they are attempts to be statistically honest about the central tendency of the data, they are the estimates that improve our accuracy, and they have error bars. We pointed out midpoint estimates and error bars complete with reproducible methods and even Github repositories so others can retrace our statistical analyses.

Our earnest scientific quest to boost the evidence base in the early COVID-19 outbreaks established many of us as contrarians, raising important questions of who, exactly, got to decide when someone in science is contrary and when they are simply the first scientists to unveil a paradigm-changing discovery.

Great Barrington Declaration

In the Summer of 2020, all eyes were on Sweden, the world’s control group.

Sweden took a “contrary” path in public health policy, acknowledging that with subclinical cases and asymptomatic spread there is not much we can do, the severity of the virus is likely to cause outbreaks that are real, but manageable with existing medical capacity, and educating people on transmission may be the best approach to mitigating the risks of the virus. Focusing protection to aid those at high risk of severe outcomes might reduce all-cause mortality & morbidity, or so wagered Sweden.

Those who lambasted us early outbreak epidemiologists estimating lower severity were also very critical of Swedish policy. There was a widespread belief in this highly vocal, online academic community that lockdowns were the superior policy. Incidentally, many of these scientists consulted vaccine makers, and vaccine makers stood to benefit enormously from this policy. Nonetheless, there were models of lockdowns showing that lockdowns stopped outbreaks and bought time for the arrival of vaccines.

In theory, that’s all well and good, but models are not reality, locking down society has costs, and those costs had to be considered, according to “contrarians”. Additionally, other models suggested lockdowns did little except delay the inevitable peaks of cases at 1-2 deaths per 1,000 capita, and lockdowns, school closures, and other severe interventions caused economic harms. Unfocused efforts to apply costly policies across everyone, despite highly imbalanced risks of severe outcomes to COVID driven by age and pre-existing medical conditions, could effectively do harm through public health policy to people who were otherwise not at risk of harm due to COVID.

There were no easy answers. Science could not make the value call on what is the “good” policy, yet the lines between science and policy value-statements blurred, and Sweden became a contested zone of sciencepolicy (hyphen intentionally removed).

In the Summer of 2020, Sweden’s outbreak peaked at 1 death per 2,000 capita, about 1/3 the peak of the NYC surge. Below is a dashboard I’d made for hedge funds, medical managers, and governors, helping them track outbreaks for real-time comparison of outbreaks that were asynchronous in time but had growth rates cross zero at similar estimates of cumulative burden. The best comparable real-time estimate for cumulative burden during the COVID-19 pandemic was lagged deaths per-capita (deaths_pc), as case ascertainment rates and care-seeking rates varied significantly across regions, hospitalizations were driven by complex dynamics of admissions, lengthy stays, and medical capacity, whereas demographics were similar-enough to allow comparison, at least noting the limitations.

The paying customers received GIFs, helping them see how these outbreak trajectories rolled forward in time and “bounced off” upper-bound lines or “herded to” less-mitigated outbreak scenarios like Sweden.

Under the theory that Jay, John, Sunetra, myself, and others were wrong, the anomalous peak of Sweden made no sense. Many believed Sweden would peak at 4-6 deaths per 1,000 capita absent a lockdown, so Sweden’s outbreak peaking at 1/8-1/12th their estimates was a major anomaly of significant public health policy importance. Under our theory that conventional estimates were 2-6 times too high, however, the Swedish outbreak peaking in the Summer of 2020 was important evidence to learn from. The dashboard above compares US state outbreaks to the Swedish outbreak, coloring outbreak curves in US states by interventions at the time, helping us see how lockdowns slowed case growth, relaxed interventions led to a resurgence of cases, and then - anomalously - cases peaked across US states at similar mortality burden as Sweden’s summer 2020 outbreak.

Due to many vocal people being very mean on Twitter, treating people like rubbish and punching down on a post-doc as if he were a tenured professor, I stopped sharing my findings publicly, so the dashboard above did not get published. It did, however, find its way into the inboxes of friends.

I felt an obligation to share what I found, but in the face of nasty rhetoric and vicious attacks on everyone who spoke up, the academic community, with the backing of health science funders spearheading an operation to warp-speed the approval of vaccines during lockdowns, sent a clear and chilling signal that it was dangerous to dissent, catastrophic to be contrary.

Jay was one of the few people I felt comfortable sharing my results with, no matter what I found. Colleagues want to help each other learn the truth and good colleagues always give each other the benefit of the doubt. In the sea of online hostilities, Jay was an unsinkable island of curiosity and grace.

With the evidence base that accumulated by the fall of 2020, including the Swedish peak and policy proposals to close schools & lockdown in the fall/winter of 2020 until vaccines arrived, the Great Barrington Declaration was published in early October, 2020. The GBD cautioned that locking down or closing schools until vaccines arrive can cause harm. Causing harm is against the Hippocratic Oaths and risks undermining trust in public health, they argued, whereas focusing protection on those at high risk of severe outcomes may minimize all-cause mortality and morbidity conditioned on there being a pandemic.

In my view, an epistemological undercurrent aiding the Great Barrington Declaration was an ahead-of-the-curve acceptance that, by October 2020 when COVID had gone global, the virus was destined for endemicity, outbreaks happened fast enough with thankfully low-enough burden that it wouldn’t overwhelm our medical system, and it is essential that managers of human health consider the entire portfolio of health outcomes, not just COVID.

If you look again not just at the dashboard above, but the paper Colleagues and I wrote here, one can learn the rigorous evidence base behind my own support of the Great Barrington Declaration. Cases in the fall of 2020 peaked at 1-1.5 deaths per 1,000 capita, consistent with our ILI findings from April 2020, consistent with the Swedish outbreak’s summer trajectory, and even consistent with later findings of waning immunity relevant for vaccines (we had estimates of waning immunity by the Alpha wave, long before the CDC found immunity waned in their study of a Delta variant outbreak in Provincetown). When enough data points tell the same story, we start to call that story a theory, and as someone who quantified the weight of evidence I came to believe the theory of lower-burden outbreak scenarios, such that the pandemic wave would not be as bad, but subsequent outbreak cycles can continue to accumulate hospitalizations and fatalities, all of which needed to be managed prudently with reducing all-cause M&M while not-causing-harm as excellent guiding principles.

I regret that the evidence base for this theory is so private, but remember that privacy was the consequence of intolerance raising the costs of being contrary. The damaging intolerance wasn’t just through informal social norms among scientists, but it came from the top of the totem pole with institutional actions by health science funders.

Devastating Take-Down

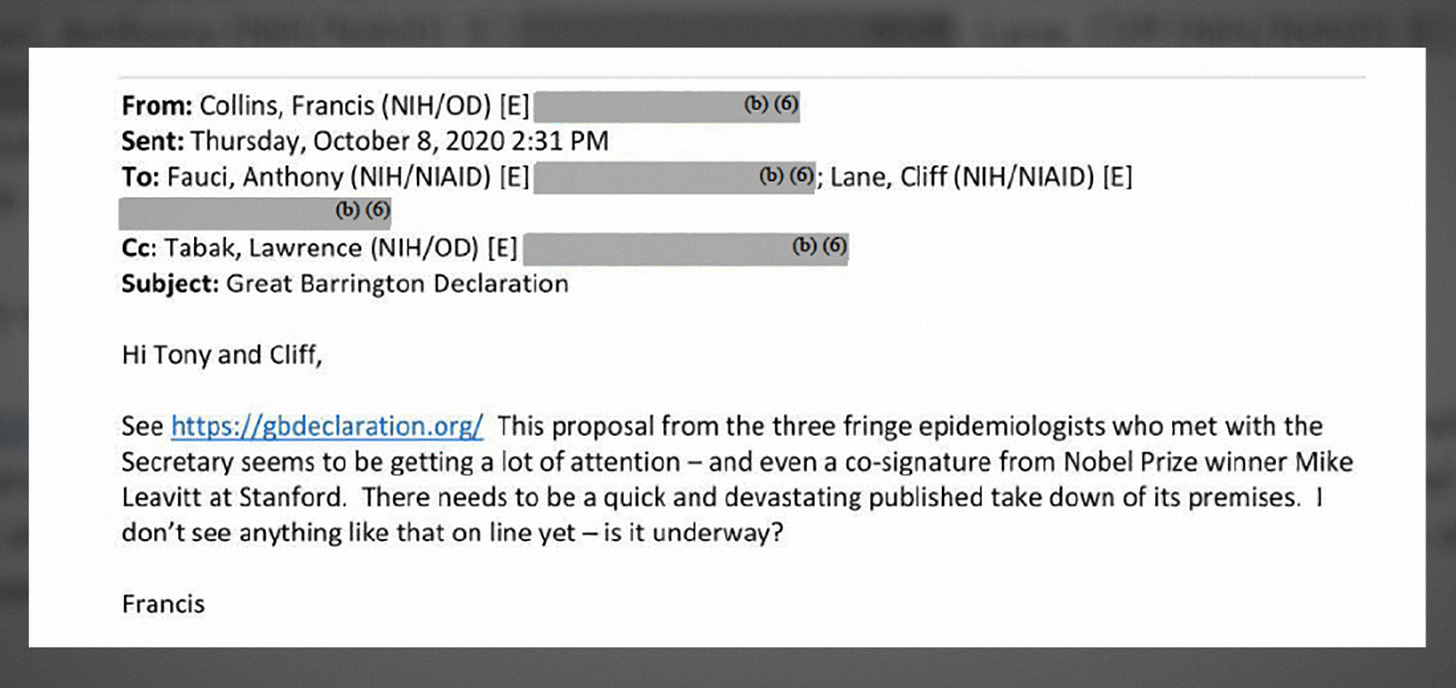

Francis Collins, then director of NIH, despised the Great Barrington Declaration. Specifically, he wrote Anthony Fauci that they needed a “devastating take-down” of the declaration written by “fringe” epidemiologists.

Shortly after Collins wrote that email, many epidemiologists close in the orbit of Collins and Fauci wrote op-eds criticizing the Great Barrington Declaration as a “herd immunity strategy”, misrepresenting the GBD authors’ sincere intentions and medical obligations to Hippocratic Oaths by saying the GBD is a proposal to “let it rip” and saying people who supported this policy were trying to “kill grandma to save the economy”. GBD supporters were called “eugenicists”, and worse.

The extreme rhetoric of many scientists during the COVID-19 pandemic is deeply regrettable. Science is, or at least it must be, an endeavor of curiosity, and curiosity is a delicate plant that withers and dies in scorching rhetoric. While scientists all have political beliefs and are respected all the same irrespective of their beliefs, when we put on our hats as scientists it’s important to focus on the data, the evidence, the methods, and the logic, and be curious about why somebody is finding something different than you. The only way to create space for different views, to really live up to the ideals of inclusivity many academics strive for, is to be graceful and curious in the face of diversity, especially diversity rooted in deep social, cultural, religious, or even epistemological differences that take time and dedicated attention to disentangle.

NIH directors desired a devastating take-down of Dr. Bhattacharya and his colleagues, and scientists close to NIH directors rapidly wrote op-eds with scorched-earth rhetoric that appeared as devastating take-downs. Employees within NIH and NIAID requested Twitter shadowban Jay. When Elon Musk took over X, he released the “Twitter Files”, revealing how health science officials pressured social media platforms to censor scientists with different views.

The Grace of Dr. Jay

If you just read the negative characterizations of me, Jay, and others who maintained independence throughout the pandemic, you might think we are some maniacal cult, fanatics hell-bent on killing people to make a profit. I’ve even been called “far-right”, which shows just how far off the midpoint our critiques land, much like their estimates of COVID burden in Sweden.

For those who see themselves as compassionate people, I ask others to imagine how it felt to be ostracized by non-inclusive scientists for sincere, evidenced-based views… and also learn that our own government, the head of our own National Institute of Health, requested a social media platform shadowban my friend and colleague for his sincere, scientific views that aligned with my own. Can you feel the chilling effect their hostility has on my own desire to publish revolutionary findings, or the damaging effect of scientific intolerance on public trust in the impartiality of scientific institutions? Betrayal, the wake of ill-intentioned departure of actions from ideals, inundated my soul as the actions of scientists deviated so harmfully from our the ideals of our enterprise. Whether the censorship was constitutional or not, it was a betrayal for an NIH director to set in motion the censorship of health scientists with different views, especially during a pandemic when uncertainty was high, and it damages trust in science when scientists are viciously unprofessional and unkind.

While I have felt the dark waters of betrayal and resentment over the mistreatment of a good man, dear friend, and brave scientist, I’ve been led ashore by a piercing ray of light that shines through.

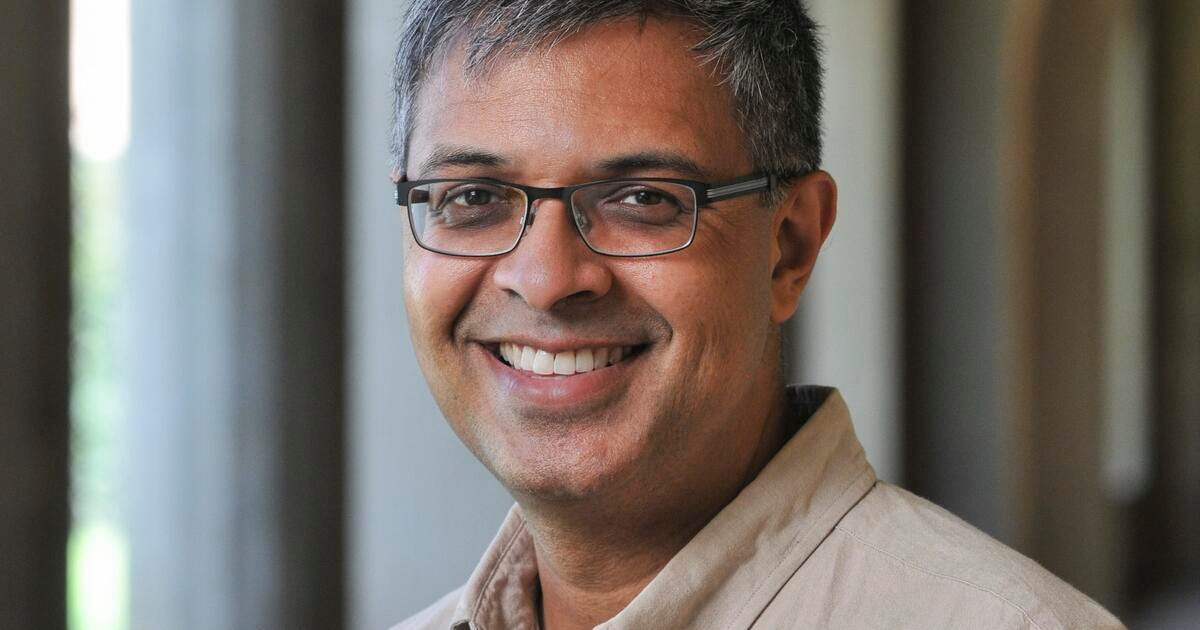

Throughout the epistemological warzone of COVID, through the onslaught of demonization, and from a pit of betrayal, I have only ever seen Jay smile and care.

When Jay smiles, it’s the smile of someone who is joyfully curious about new things, it’s the smile of a man who saw uncertainty and embarked on a serosurvey in Santa Clara County to aid science with real data, it’s the smile of someone who sees uncertainty and finds joy in others using cool skills from new fields, analyzing big data to answer large problems. When Jay smiles, it’s the smile of a man who loves the people around him and the unique skills they bring to the table, who finds the rubies in the rubbish, polishes them off, and turns them into friends.

In the rare times when Jay is not smiling, he cares. Jay doesn’t care in a superficial way, he doesn’t just pat you on the shoulder and say “gosh, that sucks.” Jay cares like an intellectual Atlas who carries the weight of the world - including your struggles - on his shoulders. I’ve seen Jay saddened by the state of science, by the diminished public trust in science & public health, by the larger excess deaths in the US versus Sweden where saner discussions & policy prevailed, by the people thrust into acute hunger by our strong policies in the face of uncertainty, by the lives we couldn’t save and institutions we have yet to repair.

… and then I’ve seen Jay smile again, curious about how we can fix it all, excited about the possibilities that lay ahead and the good that gather around him, eager to help.

It takes a unique moral fiber and commitment to love to be censored by the NIH director and rebound to being caring and joyfully curious about how to make the world better. It says volumes about the man that when hordes of scientists devour the forbidden fruit of tribalism and bias, Jay keeps seeking ideas from people who are different while caring for literally everyone, for the poor and the kids who didn’t have a seat in the policy table during COVID, for the elderly who don’t have focused protection to aid their efforts to say healthy, for the young scientists thrown in a meat grinder, told their seminal work was “kindergarten molecular biology” by professors acting like kindergartners, and more. Dr. Jay Bhattacharya cares more than most. The world would be a better place if we had more people who cared like him.

In the battlefield of COVID, I’ve witnessed The Grace of Dr. Jay.

Jay knew I quit my postdoc because of the above dashboard I felt I couldn’t share. When the rest of science seemed to abandon me, Jay invited me to the most prestigious conferences I’ve been to in my life, to MIT and Stanford where I could discuss the science-policy interface, the origins of COVID, or public health policy beside great thinkers. Jay even invited people we disagree with, because that’s Jay being the change he wishes to see in the world.

When the rest of the world wanted me to feel like I was rubbish, and when they almost succeeded, Jay helped me remember that I was a ruby.

I know many people are uneasy about the incoming administration. I understand that the health sciences are in turmoil following the COVID-19 pandemic, and I understand there could be immense fear within NIH and among the scientists who depend on NIH for funding as new leaders roll in. I am already seeing the same people who wrote the op-eds after Collins’ devastating take-downs, the same people who ghostwrote articles for Fauci claiming a lab origin of SARS-CoV-2 is implausible while knowing it is likely, the same people who demonized me throughout the pandemic, are now the same people riling up their audiences in an effort to take-down Jay following his nomination to become NIH director.

The people demonizing Jay don’t know him. They never sat down to chat science with him, because once you meet the man you will realize Jay is one of the nicest scientists alive today. The people who worry about an NIH director with a vendetta are not just ignoring that Francis Collins already acted on vendettas against Jay, they are also unaware that Jay is motivated more than anyone in the world to not repeat the harmful actions of Francis Collins.

The people afraid of Jay never learned who Dr. Bhattacharya really is.

Throughout the pandemic I’ve seen how Jay seems to know in his bones that, in hopeless and cruel times, our own mercy and grace give us hope.

We need Dr. Jay to run NIH now more than ever. In the next pandemic, which could come sooner than we’d like, we will again have scientists who disagree. We will again have divergent views on the appropriate public health policy, and we will again need scientists to maintain a curiosity and professionalism, a degree of humility and grace, that Dr. Bhattacharya lived & breathed throughout the COVID-10 pandemic.

In the future of health science funding, we will need to abandon some of the detrimental hierarchies that limit the flow of scientific information. We will need to become better at finding rubies in the rubbish, as Dr. Bhattacharya did during the COVID-19 pandemic. We will need health science funders don’t pick and choose the paradigms but rather fund reproducible science. Nobody understands what the health sciences need to restore trust better than the man who was once called “fringe” for the fault of being authentic, correct, and ostracized for it.

Even if he wins, even if confirmed as NIH director, you won’t see Jay spiking the ball. I can already imagine him smiling gracefully curious about a new idea and caring about the bigger institution of science that benefits from courageous evidence collection, bold analyses, and diverse views being shared & professionally examined.

In this time of division, distrust, and animosity among scientists and the public…

The Grace of Dr. Jay is exactly what we need.

Although I am not a scientist, I enjoy reading about science. I could never understand the refusal of the bureaucracy of public health to acknowledge natural immunity or the discouragement of even trying therapeutic drugs.

Even I, as an undergrad 50 years ago took a virology course and understood herd immunity. I couldn't believe the official propaganda.

I began following Dr. Jay and you on X.

Whenever I see a thing like cancel culture I assume it is a reactionary coverup.

It was plain to see that the NIH was fearing a revolt from their dogma from any influence the Great Barrington Declaration might have.

I am more than pleased that Dr. Jay Bhattacharya was named as the nominee for the Director of NIH.

Keep pursuing truth, Alex.

I think you have a typo here Alex. You said, “ and we will again need scientists to maintain a curiosity and professionalism, a degree of humility and grace, that Dr. Bhattacharya lied & breathed throughout the COVID-10 pandemic”. Don’t you mean “lived and breathed”? Terrific article, I apologize if I read that wrong.