Zoonotic Origin Evidence We Don't Have

Why missing evidence is significant, and adverse inference of what it could show.

The absence of evidence isn’t proof of absence. It is, however, evidence. The absence of evidence for black swans doesn’t mean there are no black swans, but it does mean that a theory proposing most swans are black is probably wrong.

For a more concrete example, imagine you invite a friend over for dinner at 6pm. You know the friend is never perfectly on time, but if it gets to 9pm and you’ve heard nothing from your friend, it’s time to reject the hypothesis that all is going according to plan and start to entertain alternative hypotheses that perhaps something disrupted your friend’s evening plans.

In our investigations on the origin of SARS-CoV-2, there is a lot of evidence we have, such as unusual behavior from researchers led by Anthony Fauci, Francis Collins and Jeremy Farrar promulgating overconfident & unsupported claims of SARS-CoV-2 origins, claims which appear to a reader in the field (me) as desperate attempts to close the book that I now want to open more than ever. We also have critical evidence on research proposals, outbreak characteristics and unusual genomic features of SARS-CoV-2; the totality of evidence we do have provides probable cause for a research-related origin of SARS-COV-2.

To the best of my knowledge, however, we have not properly discussed the evidence we don’t have. I want to talk about the evidence we don’t have, because the absence of some key pieces of evidence is inconsistent with a zoonotic origin and entirely expected under a lab origin. Consequently, as the lack of a black swan tilts scales away from a theory that most swans are black, and as 3 hours with no news tilts the scales away from a theory that your dinner is going as planned, the lack of easily obtainable evidence becomes, itself, evidence against a zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2.

The Missing Evidence for Zoonotic Origin

There are four pieces of evidence which, to me, are the most significant missing pieces of evidence. If we had them, a zoonotic origin would be more likely. Instead, we lack all of these pieces of evidence, each of which would give considerable support to the zoonotic origin hypothesis for SARS-CoV-2. These pieces of evidence are:

A geographic trail of infections consistent with animal-trade outbreaks

Evidence of higher incidence or seropositivity in animal handlers

Reservoirs: Animals testing positive with close relatives of SARS-CoV-2

Pre-COVID coronavirus genomes from the Wuhan Institute of Virology

From years spent studying spillover before COVID, I have somewhat trained my mind to have informed expectations about how likely we are to find such data as a function of time & effort, much like you have expectations of how long it takes for your friend to arrive at dinner. As silence is a statement, the lack of the evidence above is meaningful. It’s critical that members of our global jury be informed about the evidence we should expect to have by now so that the general public can understand the significance of the evidence we lack.

No Geographic Trail of Infections

SARS-CoV-2 emerged as an explosive & singular outbreak in Wuhan, far from hotspots of wildlife coronavirus diversity and within walking distance of a global hotspot for coronavirus research.

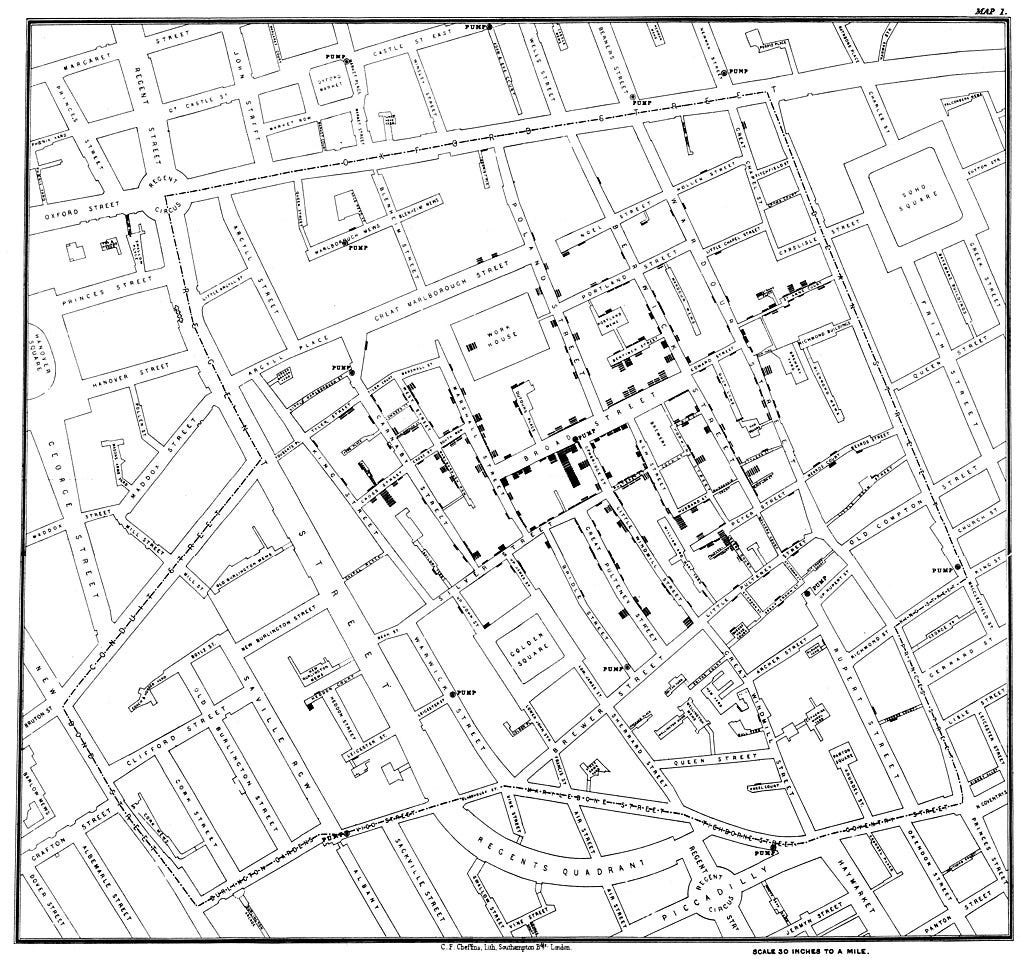

Where infections occur is a critical piece of evidence. In fact, the origin of epidemiology as a discipline is often traced back to a geographic analysis by John Snow finding the Broad Street pump to be the source of a Cholera outbreak. John Snow examined the Broad Street outbreak, drew a map of where cases lived, and found the Broad Street pump to be at the center of the cases. At the time, scientists didn’t even know whether cholera was spread by air or water, so John Snow not only found the likely source of this single outbreak, he also found critical information about cholera transmission that could be used to mitigate future outbreaks. Masterfully done, John.

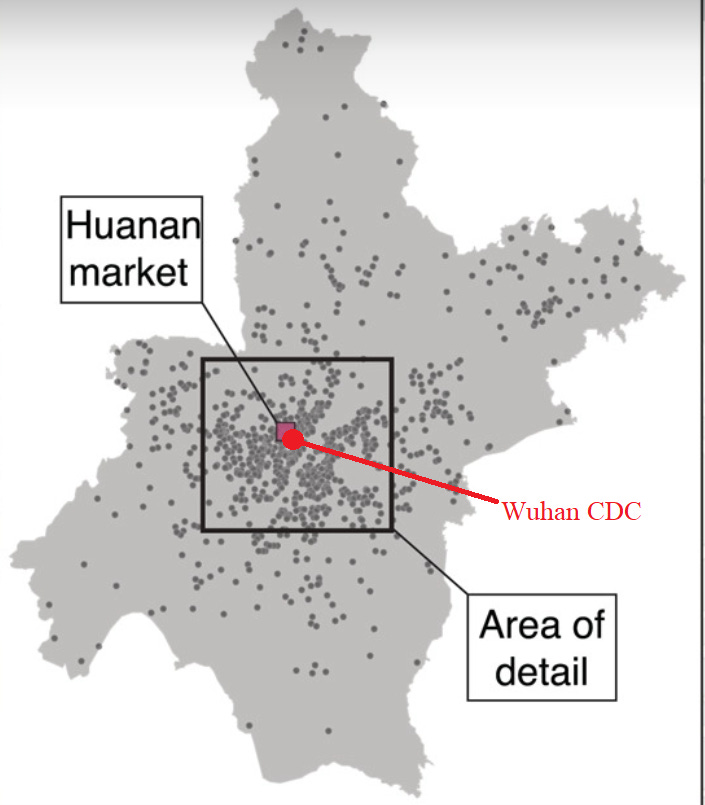

Worobey et al. - touted as the single best evidence of a natural origin, evidence the authors called “dispositive” of a lab origin theory - ran a geographic analysis of early Wuhan cases provided by the Chinese government. However, the spread of infections across Wuhan is very large and the 'centroid’ of these infections is uncertain; that uncertain centroid includes not only the Huanan seafood market, but also the Wuhan CDC. Consequently, while there was just a Broad Street pump at the centroid of John Snow’s spatial analysis, the case data Worobey et al. analyzed was provided by the Chinese government (if you still trust the Chinese government) and does not allow us to determine the location within Wuhan where SARS-CoV-2 arose.

The scatter of infections around Wuhan provides no clear geographic evidence helping us determine the origin of SARS-CoV-2. However, outside of Wuhan there is additional geographic evidence.

Wuhan is not a likely spot to find a SARS coronavirus unless it is in a lab. The wildlife diversity of SARS CoVs is highest about 1,000 miles away from Wuhan, and so the zoonotic origin hypothesis relies heavily on animal trade as the source of a bat CoV with a pangolin spike protein showing up in Wuhan. The general hypothesis hand-waves that bats & pangolins were stored in cages close together, <waves hands> recombination happens to put a pangolin spike gene in a bat CoV genome then… <waves hands> recombination happens 3-5 additional times with bats hundreds of miles apart to create an idealized infectious clone restriction map, <waves hands> recombination happens again to give a human-specific Furin cleavage site, and then spillover happens not once but twice in the same market.

There are many problems with this theory, but one stands out instantly: the geographic pattern of infections across China is not consistent with an animal trade outbreak.

Animals in animal trade networks are shipped around in a highly connected network, and so a virus from an animal in one market can plausibly find its way to animals in another market. When SARS-CoV-1 spilled over in Guangdong province, it produced a clear geographic trail of infections across the entire province. In contrast, SARS-COV-2 is proposed to have spilled over in Wuhan - twice in one month! - yet it did not produce a single additional detected animal-trade infection throughout China, even though we knew that animal trade was the source of SARS-CoV-1 and that is the first place to look for infections if authorities were unaware that this arose in a lab. The lack of a geographic trail of infections is unusual if one is to claim SARS-CoV-2 arose as a consequence of animal trade.

For the lab-origin theory, the lack of a geographic trail has a clear explanation: SARS-CoV-2 emerged as a singular, research-related event in Wuhan.

For the zoonotic origin theory, the lack of a geographic trail of infections goes against their primary hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 emerged as a consequence of the animal trade. Additional missing evidence tilts the scales further against a zoonotic origin.

No evidence that animal traders or handlers were disproportionately affected

In SARS-CoV-1, researchers in China quickly conducted a serosurvey of animal traders in Guangdong and found a significantly higher seropositivity in people who handed civets (58%) compared to people who handled snakes (9%).

In SARS-CoV-2, we don’t have a serosurvey of animal traders in a wet market, nor do we have a serosurvey of researchers at coronavirus labs in Wuhan - the latter could have been done for less than a few thousand dollars and could have either shown a lack of seropositivity among coronavirus researchers… or it could have shown a higher seropositivity of coronavirus researchers compared to the general public. Given animal traders were the index patients of SARS-CoV-1, it is shocking that researchers in China did not conduct a serosurvey of animal traders immediately - instead, there was a clear effort to suppress information on COVID coming from China and ensure all such information is first approved by the Communist Party.

Absent serosurveys, researchers sequenced environmental samples around the Huanan wet market to see if samples close to animal traders are more likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2. They found no such thing. Instead, they found that samples near animal traders were as likely to test positive as samples near vegetable traders, suggesting the wet market was more likely a site of human transmission than zoonotic origin.

From the scale of Chinese provinces showing no animal trade outbreak to the tables underneath animal cages showing no higher rate of environmental positivity of animal vs. vegetable stands, the spatial evidence of human infections that we lack for SARS-CoV-2 but had for SARS-CoV-1, evidence which is very easy to obtain, tilts the scales against an animal trade outbreak as observed for SARS-CoV-1.

Under a lab origin theory, China didn’t do a serosurvey of lab workers because they knew the answer would incriminate their labs in creating a pandemic virus. Researchers found no pattern of animal-trade infections (serological or environmental) because animal traders did not bring the virus to Wuhan.

Under the zoonotic hypothesis, the lack of a geographic trail of infections, the lack of a serosurvey showing animal traders as more likely to have been in contact with SARS-CoV-2, and the lack of a significant difference between the PCR positivity of environmental samples near animal vs. vegetable traders is all extraordinarily unusual. The absence of evidence is informative because if the zoonotic origin hypothesis were true, the evidence should be easy to obtain and could have been discovered within months of the first cases. Instead, as the dinner date has yet to arrive by 9pm, 3 hours after the stipulated time, this simple evidence of zoonotic origin has yet to arrive 3 years after the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

No identifiable reservoir

SARS-CoV-1 emerged in November 2002. Within a few months, researchers sampled 25 animals and found 6 civets and 1 raccoon dog that tested positive with a SARS CoV closely related to the strain circulating in humans. An outbreak of Nipah virus in Kerala, India, led myself and other co-authors to recommend prioritized surveillance of flying foxes in the region. Within days of infections, researchers caught flying foxes and found flying foxes positive with NiV.

While some pathogens like Ebola are difficult to find in wildlife reservoirs, most wildlife pathogens are discoverable within weeks to months of index patients, especially in a country like China with significant disease surveillance capacity and especially in Wuhan, a global hotspot of coronavirus research. We are shockingly good at finding, catching, and sampling animals, and even the WIV was involved in such efforts. We have a very clear sense of probable reservoirs of SARS CoVs helping us (especially the WIV) narrow down the probable animal reservoirs. Even when we lack a known reservoir, as we did when SARS-CoV-1 first spilled over in 2002, we can find reservoirs very quickly.

In stark contrast, researchers in China sampled 457 animals at the Huanan seafood market months after SARS-CoV-2 emergence, animals spanning a range of species, including civets, racoon dogs, and more. Those researchers looking for a SARS-CoV-2 progenitor sampled over 18 times as many animals as researchers looking for progenitors to SARS-CoV-1; while virus-hunters after SARS-1 found 7 positive samples, virus hunters after SARS-2 found nothing. If we use the SARS-CoV-1 baseline to expect 7/25 animals are positive in a reservoir-searching effort after a SARS-CoV outbreak, there is nearly zero chance of taking 457 samples and all of them testing negative. Now, 3 years after SARS-CoV-2 emerged in the human population, we have sampled hundreds to potentially thousands of bats, pangolins, civets and more, and we don’t have a reservoir. The absence of a reservoir is extremely informative given prior outbreaks found reservoirs relatively quickly, easily, and with a high prevalence we should expect (as human-to-human transmission occurs at a higher rate when prevalence is higher, spillover is more likely to occur when wildlife viral prevalence is high).

Under the lab origin theory, the significant lack of animal reservoirs testing positive has a clear explanation: SARS-CoV-2 did not emerge from animals, it emerged in a lab. Animals were not the reservoirs. Researchers in Wuhan went ahead with risky gain-of-function research to create a novel virus not found in wildlife, and hence we are not finding SARS-CoV-2 progenitors in wildlife because it was made in a lab.

Under a zoonotic origin hypothesis, there was hypothetically enough virus circulating in animals to cause two spillover events in one month in the same market, but there was not high enough prevalence to detect a single positive reservoir despite the commonality of prolonged viral shedding now documented for SARS-CoV-2. Zoonotic origin proponents claim that maybe China is hiding animals, but why would they hide animals now when they were transparent during the SARS-1 outbreak, avian influenza, and other emerging infectious diseases popping up in China?

If we’re allowing the possibility that China may be hiding something, let me tell you about a government-funded lab doing CoV research in Wuhan that hasn’t been allowed to speak to reporters since the start of the pandemic… Let’s talk about data that we know exists but hasn’t yet been released.

The Coronavirus Dataset from the Wuhan Institute of Virology

The single most important dataset in the world to understand the origins of SARS-CoV-2 is a database of reportedly hundreds of unpublished coronavirus genomes sequenced at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. This dataset was taken offline in 2019, and it has not been released. The entire database would likely fit on a thumb drive and, if a natural origin were true, this dataset would single-handedly reject a laboratory origin by revealing an expansive set of pre-COVID coronavirus genomes that help us see the natural evolution more clearly.

Unlike the challenges of finding & catching bats or ascertaining cases across an entire province, the WIV dataset exists on computers & could be transferred anytime; it is the most important dataset of the pandemic, it is, in theory, the easiest dataset to obtain since it already exists. If a zoonotic origin were true, this dataset would remove all doubt & exonerate the lab that owns the dataset… yet, this dataset has not been released.

Why not?

Under the lab origin theory, it’s obvious why the Wuhan Institute of Virology, and the Chinese government more broadly, would not release the dataset: it contains the progenitor virus that was manipulated to create SARS-CoV-2. Under a lab origin theory, if we saw their dataset, it would reveal immediately how they constructed SARS-CoV-2, likely modifying restriction sites to create an efficient reverse genetic system, possibly adding additional sites (e.g. BsaXI) to enable the insertion of a Furin cleavage site, and we would see a progenitor lacking the Furin cleavage site alongside the lab construct with a furin cleavage site inserted.

Under a zoonotic origin hypothesis, it’s not really clear why China has not released this CoV dataset. After all, if a zoonotic origin were true then releasing this dataset would be the single best way to disprove the lab origin theories - it would reveal the natural evolution of coronaviruses from expansive pre-COVID sampling and reveal that the WIV had no unpublished backbones of SARS coronaviruses, no evidence of following the research program proposed in the DEFUSE grant.

The only reason one might imagine both a zoonotic origin & an unshared dataset is if the dataset contains biosecurity secrets - most likely, bioweapons or novel biological agents with enhanced functions. But, if the Wuhan Institute of Virology has novel biological agents on a database, it would be quite the coincidence that Wuhan should be the site of emergence for the first ever SARS coronavirus with a Furin cleavage site (as proposed by the WIV in the DEFUSE grant), with the most infectious-clone-looking restriction map of any published coronavirus (as proposed by the WIV in the DEFUSE grant), producing a single outbreak in Wuhan with no geographic trail of infections characteristic of an animal trade outbreak, no animal traders testing positive, and no reservoirs to be found.

The Absent Evidence is Evidence Against Zoonotic Origin

As surely as you question your friend’s evening when they are a few hours late for dinner, the absence of evidence for a zoonotic origin is significant in and of itself. We lack a geographic trail of infections. We lack evidence of animal traders having a higher incidence or PCR-positive environmental samples compared to vegetable traders. We lack a reservoir in Wuhan with a SARS CoV despite extreme sampling, and in fact we lack a single documented case of a furin cleavage site in a SARS-CoV outside of SARS-CoV-2. While a spatial analysis of early outbreak cases provided by the Chinese government centers around either the Huanan seafood market or the Wuhan CDC, the Chinese government has not released the one database of pre-COVID coronaviruses under study in Wuhan that could, under a zoonotic origin, exonerate their labs.

The evidence we lack paints a clear picture: the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 is not consistent with an animal trade outbreak. Furthermore, the suspicious withholding of coronavirus genomes sequenced at the WIV, evidence which would exonerate the labs if a lab origin were false, suggests that the dataset being withheld contains information as bad or worse than persistent suspicions that a Chinese lab created a virus that resulted in over 18 million deaths, or three times the death toll of the Holocaust.

Adverse inference suggests that database, communications, and laboratory notebooks withheld by researchers in question much like the DEFUSE grant was withheld and only released unwillingly, reveal the clear laboratory origin of SARS-CoV-2.

Brilliant. Thank you for your insights and analyses.

Good analysis. Having read a few others, the conclusion seems irrefutable. Having read The Real Anthony Fauci, the proposition that the US CDC or NAIAD commissioned and supervised the WIV work and bear a significant share of the responsibility for lab protocols and therefore leak, might suggest a US-China agreement to stay schtum about origins and data.