Automating Biology

Human machines will accelerate our study of nature's machines

Living organisms are nature’s machines.

Over the past several months, I’ve been developing automated lab technologies, vibe-engineering embedded systems that will explore biology in a way that I’ve always wanted to explore life’s possibilities. As I work with my best friends and we discuss the interface between engineering, economics, and biology, I’ve refined my views on AI and automation in biology.

For those just joining, a little intro: I’m a mathematical biologist with degrees in both, I received my PhD from Princeton’s program in Quantitative and Computational Biology, ran a successful scientific consulting company, worked for over a decade on problems in quant + fundamental investing, worked at Sandia National Labs on artificial intelligence and complex systems for national security, and more (e.g. I did the bioinformatics and statistical analyses in one of the most impactful papers providing evidence consistent with a lab origin of SARS-CoV-2). Now, I’m starting another company at the intersection of AI, automation, and biology.

Before doing AI or automation for something, it pays dividends to understand the nature of that something. Biology is the study of life, and we can understand that once we understand “life” and “the study of” it.

Living things are nature’s metabolic machines. All living things contain genetic material, a special language of chemicals in a sequence of DNA or RNA, and that genetic material encodes proteins. Proteins, in turn, do things. Proteins can be structural, forming the hair on your head or callouses on your hands, and proteins can be functional, from the hemoglobin carrying oxygen from your lungs to your muscles and insulin regulating blood glucose levels to the receptors helping neurons talk to one-another, the enzymes in your stomach breaking down your food, and more.

These metabolic machines in nature come in many forms at many scales. At the simplest form, there are proteins that do things, effectively tiny modules of metabolic and structural function like a software packet controlling a motor or sensor an engineer can use to build a robot. Beyond proteins, there are organisms in the form of everything from viruses in capsids to cells in phospholipid bubbles.

Cells themselves become another module of metabolic and structural function, effectively (in computer science speak) a layer of abstraction allowing larger structures and functions to be built by coordinating cells without needing to interfere much with the messy code inside cells. Multicellular organisms can range from relatively undifferentiated blobs of cells that all share some crude social contract to help one-another or cooperate in some fashion to the largest living organisms full of trillions of differentiated cells, some cells that form muscles and allow for movement, other cells that form neurons to control the muscles, cells that produce enzymes to digest food, cells that form the walls of our innards to contain digestion while absorbing nutrients, cells in your eyeballs detecting light to read these words, cells in your skin forming a protective sack preventing your water from evaporating (unless it’s useful for regulating body temperature by sweating), cells forming a standing immunological army inside of you to ensure your country of cells is protected from invaders, and more.

From genes, proteins and metabolites (the chemicals living things use, such as sugars, fats, nucleic acids, and more), to cells, tissues, and broader organisms, life can be meaningfully viewed as layers of abstraction of chemical processes with the common feature of self-replication at some layer of abstraction. Our skin cells don’t exactly self-replicate, but our human forms do; our ancestors form a chain of replicating things connecting our forms today all the way to the first self-replicating ooze over 3.6 billion years ago.

That’s life.

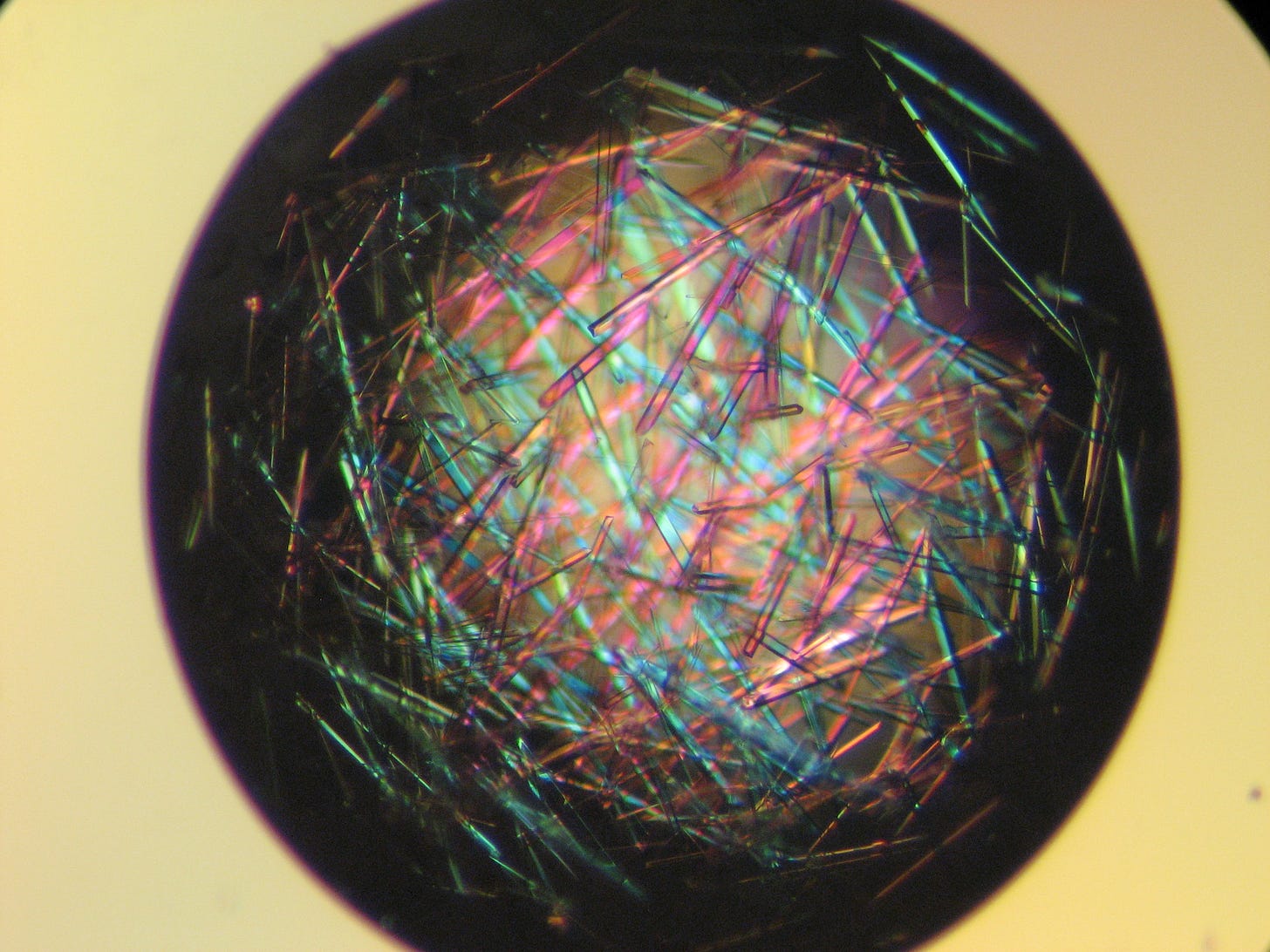

The study of life looks at all of these things - genes, proteins, metabolites, cells, tissues/organs, organisms - as well as how these things interact. We study genes by sequencing them. We study proteins by measuring their structural and functional properties and by imaging them. This is easier said than done. To image a protein, you organize the same protein into a crystal lattice, blast that lattice with a beam of X-rays, and use the scattering of light to infer the structure of atoms in the protein. Below is a pretty picture of some crystals I made when studying the structure and function of a class of proteins used to break down penicillin - we shot those crystals with an X-ray cannon and learned cool things about how that protein’s structure determines its clinically relevant function.

The study of life isn’t limited to genes and proteins but also examines cells, tissues, organisms, and how they interact. Cells are action-packed bubbles full of complicated genetic scripts encoding thousands of proteins, proteins doing many different structural and metabolic functional tasks to keep the cell intact, help it acquire nutrients and whatever else it takes to complete the cell’s life cycle to divide again. The method my mom and I conceived to maximize the efficacy of her chemotherapy regimen to treat pancreatic cancer, for example, relied on a clever hacking of cell cycle dynamics by controlling how much glucose (a metabolite) is available to cells and when we activate those intracellular processes relative to the timing of infusions. Our method wasn’t just cell biology - it also relied on some insights about the pancreas as an organ, the cell types in the pancreas and their unique relationship with glucose. The study of life spans scales of many living structures and their chemical processes.

And then there are organisms, complete with physiology and complex functions across organisms, all of which I like to summarize as my sensei did: we’re all bags of bitchy, demanding enzymes. That’s to say, most of what we do as walking, talking organism can be traced back to some enzymatic requirements much like the weirdness of your computer traces back to some core hardware and operating system quirks. When you get hot, you power your massive muscles to walk to the shade and possibly sweat to maintain a constant body temperature. You maintain a constant body temperature because your body is full of many enzymes trying to maintain a complex balance of chemical conditions. Increasing body temperature changes the rates of the many chemical reactions inside the body in ways that can upset the delicate chemical balance or homeostasis our bodies try to maintain.

Beyond organisms, the study of life also concerns itself with how organisms interact, leading one beyond into the broader field of ecology, a field I’ve loved since I was a kid. I could talk at length about ecology and some ways we can use algorithms I’ve developed to better study it, the tools we use to study organisms in nature, and more. There is already some automation in ecology, but it’s a relatively boring kind - temperature and other climatological sensors, camera traps, satellite imagery, and other tools help us understand the environment organisms live in and survey organisms passing by. Some people are trying to use AI tools to understand the languages of birds and whales talking with one-another (birds to birds and whales to whales, for now at least), so don’t write off ecology but note that it’s harder to manipulate ecosystems because they’re often quite large and the legality of doing so not as permissive as what we’re allowed to do with cells and proteins.

That’s life, and the study of it.

Now, on to automation and AI.

Automation is an excellent term that makes it easy for us to conceptually explore the overlap. Quickly, I hate the term “AI”. “AI” is hype, and that’s not a bad thing as it gets people thinking in fantastical ways, living in clouds of imaginary possibilities, but it’s a limitation when we’re trying to shrewdly help the rubber hit the road. The term “AI” can often have our imaginations float away like a philosopher in the clouds whose feet leave the grounding facts of the core structures, functions, inputs, outputs, benchmarks, and workflows that define the specs of this tool. My preferred practical rebrand of “AI” is “digital automation” - ChatGPT is like an assembly line that automates the production of text. Claude is an assembly line that automates the production of code, images, videos, and more. Large action models (LAMs) automate the execution of digital commands. Referring to these tools as “digital automation” might not be as sexy as “AI” but it helps me talk about the same thing without fantasies of supernatural functions. Instead of automation and AI, let’s talk about physical automation and digital automation.

Why does automation matter? Automation lets machines and processes in nature do repetitive tasks for us, helping us do more of them, increasing productivity, decreasing costs, and allowing us to spend time and energy on the next rate-limiting step for whatever goals we’re trying to accomplish in life. If I find a task that pays 10 cents to accomplish it may not be worth doing, but if automation can help me do 10 million of those tasks at the cost of 1 cent per task, then suddenly we’re in business.

Physical automation comes in many forms in the study of life. Physical automation allows us to automate the production of labware, such as the injection molding of 96 well plates and mass-production of pipette tips that are the lifeblood of sterile lab work, and automate the execution of laboratory processes such cycling between hot and cold temperatures to catalyze important reactions (PCR in thermocyclers) or automate the tedious task of pipetting of 96 things in said 96 well plates.

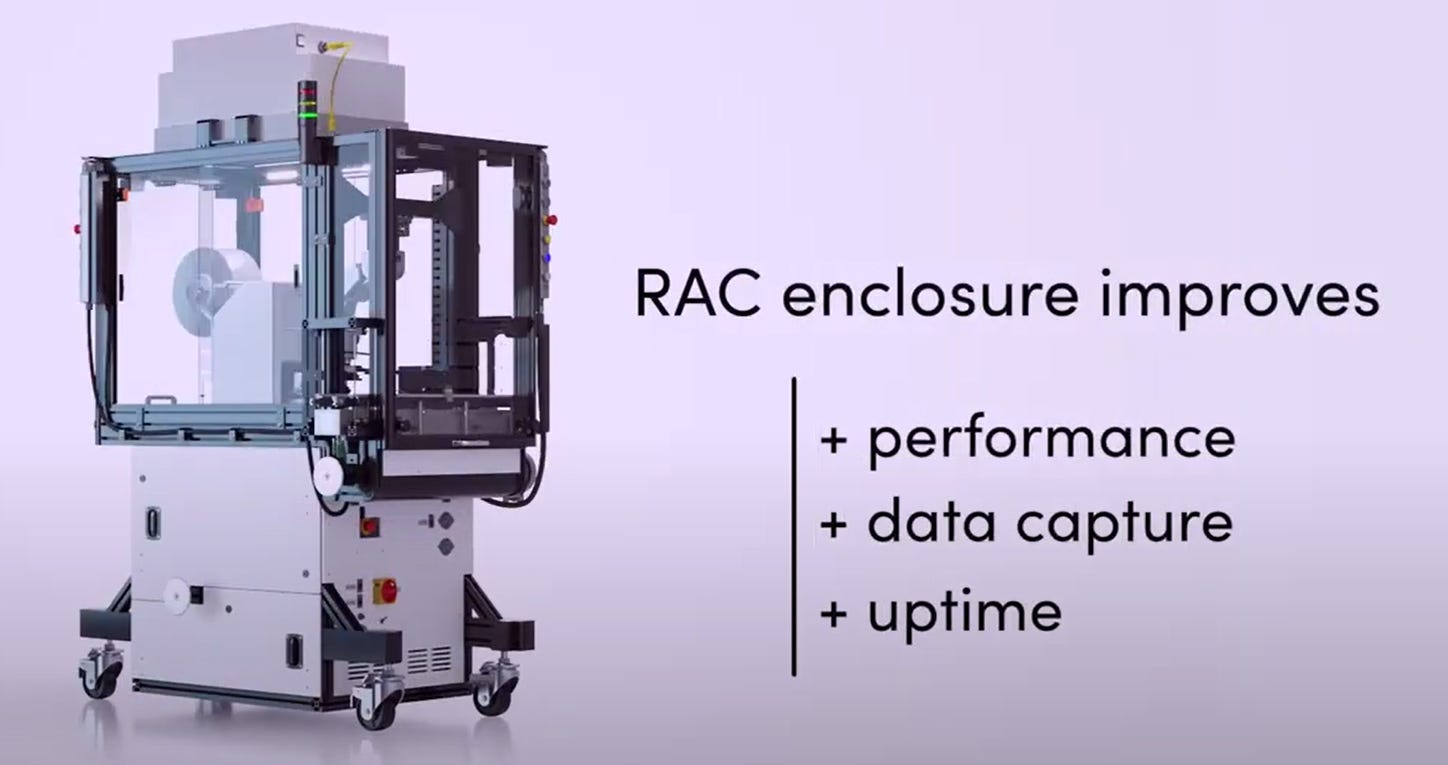

An important development du jour in physical automation for biology is the concept of a cloud lab and lab automation tools such as Ginko Bioworks’ “Reconfigurable Automation Carts” or RACs. Below is one of Ginko’s RACs, along with the benefits of using them to increase performance, data capture, and uptime. I’m not affiliated with Ginko and I don’t own any DNA 0.00%↑ shares, but I might soon, because I think they’re onto something. I’ll share of what is effectively my market thesis for physical automation in biology below, but wanted you to see the cutting edge of automation to bring this idea to life: cloud labs aim to allow anyone to sit in their computer and order laboratory services executed in a machine like the one below.

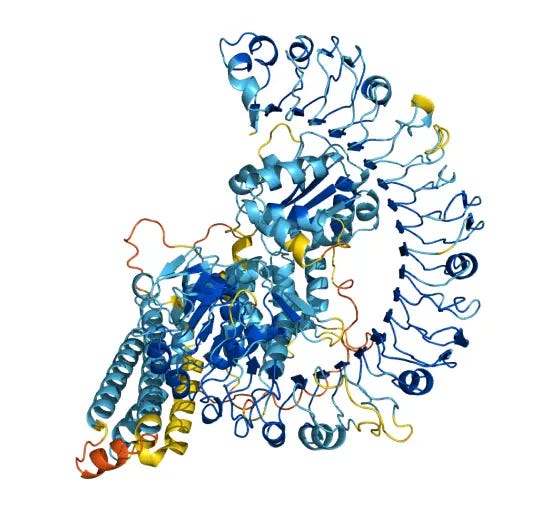

Digital automation is similar to physical automation, but the most prominent digital automation tools in modern biology focus on automating the inference of data we don’t have. Most commonly today, digital automation focuses on inferring the structures and functions of potentially therapeutic proteins or metabolites that bind onto proteins. The impressive digital automation of modern “AI biodesign tools” du jour has relied on several decades of people doing the X-ray cannon type experiments I mentioned earlier, curating databases of genes, their proteins, and 3-D structures of said proteins. By training cool mathematical tools on these datasets, AI biodesign tools have proven pretty darn good (but not Godly) at predicting the structures of proteins and chemicals binding proteins, such as the messy-looking yet useful structure below.

Automating biology, through both physical and digital automation, could help us automate some of the more tedious, repetitive, and hard processes inherent in our study of life. If you’ve ever worked in a lab, you know how tedious, repetitive, and hard many experimental protocols can be, and you’ve probably either put the human in some human error or looked at a few, painfully collected data points and wondered how much cooler your study would be if you had 10 times as much data.

The value proposition of automating biology is simple: cheaper experiments, higher throughput, more data, faster innovation.

The reason nobody has done it before, however, is worth pondering. Some very focused processes have already been automated, the most prominent being thermocycling (imagine how much a pain in the shoulder it was to switch your samples from hot baths to cold baths 20 times) and fluid handling i.e. automated pipetting and potion-mixing.

Biotech has some really impressive machines that could be viewed as automation, but are more appropriately (in my opinion) viewed as platform innovations. Sequencing, high throughput flow cytometry, and mass spectrometry come to mind as technologies whose improvements in the same task have dropped costs and dramatically increased the data we can obtain from even single cells. There are components of automation to these platforms - the chemistry of Illumina’s sequencing combine with its sensing and management of chemical reactions to enable massively parallel sequencing of DNA, the encapsulation of cells in droplets combined with mechanical control of droplets and sensing systems to enable single-cell analyses, and more. However, these tools aren’t exactly “automation” in the sense of Ginko’s autonomous labs and the broader cloud lab category people are trying to define.

Autonomous labs, broadly speaking aim to allow users to perform a series of laboratory protocols without ever having to step in the lab. There are many ways people are pursuing autonomy, from robotic arms and humanoid robots to RACs connected by conveyor belts shuttling 96 well plates and other collections of fluids along to their next station. Autonomous labs capitalize on synergy between the many devices and technologies biologists often use, e.g. to get a dataset of DNA sequences you may have to use a thermocycler, then a Hamilton fluid handler, then an Illumina or other sequencing device with trips to centrifuges, vortexers, and other common benchtop devices scattered about.

Automation can in principle lower labor costs and reduce human error yielding cheaper experiments. Automation can also allow us to 10X a protocol by throwing money at it or using a 96 well plate instead of 10 tediously mixed potions in Eppendorf tubes, thereby enabling higher throughput for more data, faster innovation.

There are, however, two additional factors limiting adoption: trust and flexibility.

I would never, for example, trust a Chinese cloud lab to protect my data given the way the Chinese government has shown no regard for private property, trade secrets, and more. Giving samples to Chinese cloud labs risks handing away your secret sauce to some Chinese company. There are, however, more aligned incentives to trust non-Chinese cloud labs such as Ginko, as these companies rely on trust and their governments respect private property (including your proprietary data), patents, and trade secrets.

Laboratory scientists also want flexibility. Sometimes science works in unexpected ways. Sometimes we try to purify or amplify DNA from a sample, find there is too little, and amplify the DNA some more. Sometimes we try to digest DNA with molecular scissors only to find the scissors we chose didn’t do a good enough job delineating DNA markers we wanted. Sometimes we try to use PCR to detect DNA in a sample, such as PCR tests used to test for COVID, only to find that some primers in the PCR test aren’t working (this may indicate a novel variant, or may indicate something else requiring more flexible debugging).

Flexibility isn’t just a necessity for debugging protocols and tailoring experimental design to specific peculiarities of the living system we’re studying, it’s also part of what people love about being a lab scientist. When you’re in the lab, you have cabinets full of potions, benches full of cool devices, and a mind full of imagination inspiring you to try new things. New protocols are developed every day to improve our ability to sense subtle metabolic or other features in living systems and modify living systems to do clever new things. To put simply, a challenge of automating science more broadly is that it’s science, it’s constantly changing and innovating not just how we think about the world, but the tools and methods we use to measure it.

If someone had built an automated sequencing platform in 2000, it would’ve been obsolete in a few years. The rapid pace of technological advancements complicates inflexible automation, and this is why companies focus on autonomy, defined as automation of very diverse tasks. Ginko’s RACs, for example, could be filled with any new benchtop device. You can add another RAC if you want a new device. If a device such as an Illumina sequencer becomes deprecated and customers demand the newer device, it would be trivial to add the new device to a RAC, add that device’s new service to their menu, and adapt to the fast pace of advancements in biotech methods and hardware.

One promised summit could be automating workflows required to validate AI biodesign models. I can sit at home and predict the structure of proteins with these new digital automation tools, but how much would it cost to validate that prediction? X-ray cannons are huge and while automation is possible the whole protocol for validation is quite complex. You have to take the sequence I generated, create the entire several-hundred-base-pair sequence from scratch, put it into a plasmid, put the plasmid in a cell, culture the cell population, sonicate or otherwise pop all the cells, centrifuge the guts, get rid of some of the irrelevant cellular guts, put the remaining guts through something like a High Pressure Liquid Chromatography column, extract the exact band in that column corresponding to the thing I wanted to make, then clip off any tails (such as a His-tag) used to separate that one band of “My Protein” from the other dozens to hundreds of proteins and guts in the column, then you need to go through another complex potions exploration to find a way to crystalize that thing (I hope it works, otherwise you run out of the protein and have to do the aforementioned process again), then you can mount it on an X-ray cannon and shoot it, then you get data. Whew.

There are other options. I think this distant summit can be reached, but that way to do so is another Substack for another day.

For now, I want to leave you with some inspiration. Biology is wildly complex, our understanding of biological systems just scratching the surface. We have studied and characterized in the lab but a miniscule fraction of the genes and proteins that we’ve found in nature. We’ve cultured, studied, and characterized a similarly microscopic fraction of cells and organisms that we know exist in nature. Automating biology is the moonshot of biology: in the process of trying to put a man on the moon, we developed rockets that populated Earth’s orbit with satellites that image the earth & enable communication. Automation will require significant investment to achieve exit velocity, but once we build that rocket we’ll be able to explore the galaxies of genes, proteins, and microbes living all around us. In addition to thrilling discoveries, I’m confident these developments will pave the way for novel therapeutics that improve health and longevity, boost biomanufacturing, and more.

Let the era of automated biology begin.

Fascinating stuff you are doing. Your first sentence "living organisms are nature's machines" is a dramatic one that caught my interest right off the bat. I am writing a paper to give a better answer to Erwin Schrodinger's question What Is Life? Like you, I came to the conclusion that living organisms are machines. They are not just like machines, they are machines. That is what life is.

Alex, do you agree that there is an overlap in the Biostrategic Domain here as per

Will Douglas Heaven's article?

https://www.technologyreview.com/2026/01/12/1129782/ai-large-language-models-biology-alien-autopsy/?utm_source=linkedin&utm_medium=tr_social&utm_campaign=NL-WhatsNext&utm_content=01.27.26

Exploring where your work here fits in the emerging tech profile of concerns.

https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7412815459139391488?commentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Acomment%3A%28activity%3A7412815459139391488%2C7422066348165378050%29&dashCommentUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afsd_comment%3A%287422066348165378050%2Curn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A7412815459139391488%29