From the same virologists who gave us the flawed, NIAID-prompted “Proximal Origin” piece, the flawed Pekar et al analysis of early SARS-CoV-2 evolution, and the flawed Worobey et al. claim of “dispositive” evidence that seemed only to dispose of any future use of the word “dispositive”, we have another media blitzkrieg dropping bombs of over-hyped, under-performing work.

We did not hear about this work from a slow-growing consensus among independent scientists, nor from the observation of some incredible natural phenomenon like a Higgs Boson or gravitational waves.

No. Not in modern virology, my friends.

We heard about this work from headlines at The Atlantic claiming “the strongest evidence yet” for a wet-market origin of SARS-CoV-2 has been discovered. We don’t have a peer-reviewed paper, we don’t even have a pre-print: we just have reports that some preliminary work was shared in a talk. We don’t even have the talk. In fact, we don’t even have the code or data used in the analysis. We have nothing more than a game of scientific telephone. Gao et al. uploaded a dataset, Proximal Origin authors stumbled upon this dataset “by pure happenstance”, ran a preliminary analysis, jumped at a finding that confirmed their biases, told the WHO SAGO about it, exploited their fame to tell the largest media outlets in the world about the preliminary analysis, and now RACCOON DOG is blaring on global megaphones with jumping headlines and overconfident language while the data that started this scientific Rube Goldberg machine has now conveniently disappeared.

This episode is the most desperate, farcical episode in a series of increasingly outrageous, farcical episodes. These unjustified scientific media blitzes feel, to any reasoned skeptic, especially a seasoned skeptic with knowledge of what serious scientific discoveries look like, more like propaganda campaigns than diligent truth-digging efforts. These farces have turned The Atlantic, The New York Times, and The Guardian into the Three Stooges of SARS-CoV-2 origins reporting.

Enter the legendary Richard Ebright, stage left:

Exit The Legend, stage left.

While the media pummels us with unreviewed, unshared preliminary findings as “the strongest evidence yet”, what can the honest skeptic thirsty for truth in a sea of undrinkable spin deduce? What can we say about this talk that nobody’s seen regarding data nobody will share and everyone seems to have deleted?

TLDR: if this is “the strongest evidence yet” for a zoonotic origin, then there is no evidence for a zoonotic origin, because there is no evidence here.

The underlying study: Gao et al.

You’ve already heard a lot about “Gao et al.”: it figures prominently in the case for a lab origin of SARS-CoV-2 as a clear example of researchers looking for evidence of a zoonotic origin and finding nothing.

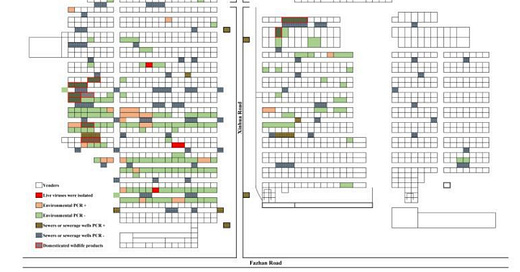

Gao is the head of the Chinese CDC. Shortly after a cluster of cases was discovered in Wuhan in 2019 with connections to the Huanan Seafood Market (HSM), Gao led a team of researchers to study the shut-down Huanan Seafood Market. Gao et al. sampled surfaces around the market and animals that were present at the time. The market was shut down, so there were no vendors present, and it’s not clear how much the team sought out animals sold by vendors. Nonetheless, Gao et al. managed to sample over 450 animals as well as many surfaces around the wet market. No animals tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, but many surfaces did. They presented the map below showing which surfaces tested positive:

Gao et al. found no significant differences in the percent of samples testing positive under different kinds of vendors, including livestock vendors (14% or 5 out of 36), wildlife vendors (11% or 1 out of 9), and vegetable vendors (25% or 2 out of 8).

Of the 64 environmental samples that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, Gao et al. then went further to do “metagenomic sequencing”, or basically sequencing every little chunk of genetic material in the area. Since we have the full genomes of so many animals, plants, and more, we can usually look at a long strand of 100 base pairs and say “that read belongs to a human” or “that read belongs to a banana”.

There are two main types of genetic material: DNA and RNA. We’ve glossed over this difference before, but right now it’s important we stop and talk about it because it matters when readying our ears & minds for the paper from the pre-print from the talk that nobody’s seen but everyone’s reported on as “the strongest evidence yet”.

DNA is the stuff in our human genomes. It’s typically double-stranded, forming the double-helix we all imagine when we think of DNA. DNA is very stable - DNA can persist for hundreds to thousands of years, enabling us to sequence the genomes of Mastodons that went extinct thousands of years ago.

RNA is similar to DNA, except it’s much less stable. RNA is often single-stranded. While this isn’t biochemically exact, my mom was a molecular biologist and she told me a bunch of tricks to understand molecular biology when I was a kid (not quite kindergarten, but young). For DNA vs. RNA, she told me to close my eyes and imagine DNA as stable because it’s like a ladder, and RNA is unstable as if you cut a ladder in half so that single strand wobbles & breaks. Recap: DNA is stable, it lasts hundreds to thousands of years. RNA is less-stable and can denature or degrade in a matter of days, weeks, or months (depending on the temperature, the presence of RNA-breaking enzymes called “RNAses” etc.).

The SARS-CoV-2 genome is a single-stranded RNA genome. It’s unstable. In order to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genome in an environmental sample, researchers have to convert the unstable RNA into a more stable DNA copy. Gao et al. did this - they used “reverse transcription” to convert RNA in the environment into a “cDNA”, a “complimentary DNA” copy of the environmental RNA. (sidebar: “transcription” is what our bodies typically do: transcribe DNA into RNA, so RNA can then be “translated” into proteins like hemoglobin… “transcription” goes from DNA to RNA, “reverse transcription” goes the other way).

Recap: Gao et al. reverse-transcribed environmental RNA into cDNA, and then sequenced the shit out of it to study the genetic material in the environment around SARS-CoV-2.

Now, close your eyes and imagine you’re in a wet market. There are animals in cages and people nearby. Every multicellular organism is a giant mass of up to trillions of cells, a veritable titan were we the size of individual cells. If you looked up these titans, you’d see many skin cells sloughing off constantly, hair shedding, with spit spewing and feces from animals depositing all manners of human, animal, bacterial, fungal, and protozoal cells. Chunks of turkey sandwiches fall from the sky like multispecies comets of birds, lettuce and wheat. Soup is spilled like a torrential downpour of vegetable spices and animal flesh. In slow-motion, the rain of genetic material falling from titans would look like violent leaves falling from canopies in the autumn, and this rain would continue every single day for years.

If you imagine shrinking yourself to the size of a cell, the floors would be Grand Canyon-esque sedimentary stacks of cells formed by years of genetic leaves littering on the floor of a forest. The genetic Grand Canyon, with all its layers and depth of time and complexity of sloughing cells from titans past, would be decomposing slowly, a mixture of genetic material connecting the freshly fallen leaves today with the genetic leaves from years past. If you shrunk yourself even smaller, to the size of DNA, you’d see this continental mass of cells is full of DNA and RNA; this molecular leaf-litter in the environment of the Huanan seafood market would be a treasure trove of genetic material from a long history of multi-trillion-leaf organisms sloughing off genetic material for years in that marketplace.

Then, one day, Gao et al. enter the room with a shovel the size of Manhattan, scoop up this entire forest floor, and sequence it. That’s the dataset of interest.

The sequences returned will be a mix of RNA and DNA from the entire history of genetic “rain” in the market. The sequencing effort wasn’t unbiased: Gao et al. used a method designed to filter out human RNA and DNA. We already know humans are present. Finding human genetic material in a human environment is not very interesting, but perhaps finding specific animal genetic material correlated with SARS-CoV-2 might reveal a hypothesized reservoir. It’s a promising idea, and I commend Gao et al. for examining it under the trying circumstances of an early outbreak that led to a pandemic.

Before we ever read the paper from the pre-print from the talk that nobody’s seen, and before we see the data that everyone seems to have deleted, we can use the methods of Gao et al. and our empirically grounded imaginations of environmental sequence deposition to anticipate the nature of the data and, as a good statistician, anticipate some limitations in the data while conceiving the analyses we need to see a priori.

Limitations in the Gao et al. metagenomic dataset

When scientists point out “limitations”, we’re not being jerks. We’re just being honest. If I measure my height, there’s a limitation: my height does not tell me my weight, blood pressure, heart rate, and other quantities of physiological interest, so a dataset of heights has limitations. If someone said they had a dataset of human height & used it to find relationships between cholesterol and heart disease, I don’t have to look at the dataset to call bullshit. For complex models and datasets such as the metagenomic data obtained from environmental surveillance, limitations may be less obvious, so it’s important we examine the nature of the data closely and present limitations in the most transparent and comprehensive way possible.

The sampling procedure for metagenomic data

First, any statistician counts samples and critically examines the sampling process. While there are 64 SARS-CoV-2 positive environmental samples, only 27 samples were sent in for metagenomic sequences. Which samples were these? Were they drawn at random, chosen ad hoc (random-ish choosing by squinting and shooting-from-the-hip, but potentially prone to human biases), or were they prioritizing sequences near animal stalls?

This is an exceedingly important question. If SARS-CoV-2 positive samples were truly chosen at random for metagenomic sequencing (an almost impossible thing to do in practice), then we could look at correlations between the relative abundance of various organisms’ genetic material and SARS-CoV-2. Correlation does not imply causation: in the leaf-litter of genetic material, we can’t tell which organism was infected, only that some genetic leaves were more common in areas with more SARS-CoV-2.

If researchers say that non-human animals are in 100% of the samples, but the 27 samples were all from animal vendors, then the statement “100% of SARS-CoV-2 positive metagenomic samples had animal DNA” tells us nothing, as it was the consequence of metagenomic sequencing of samples under animal vendors and not, say, banana vendors. The sampling process is a major limitation, preventing us from inferring a reservoir or even showing a correlation between animal genetic material and SARS-CoV-2.

Removal of human genetic material with an enrichment kit

When Gao et al. removed human genetic material in an enrichment kit, they added a critical technical limitation to their data. Gao et al. don’t report exactly which enrichment kit they used, so all we can know for sure is that some lab protocols were run in a way that removed human genetic material and, like any lab protocol, the extent to which human genetic material was removed likely varied from sample to sample. Suppose humans were 50% of the genetic material in all samples prior to enrichment, it’s conceivable that after removal humans could account for 5% of the genetic material in one sample and 20% in another, with the 4-fold difference in human genetic material due entirely to this step of removing human genetic material with an enrichment kit.

This means that we can’t look at e.g. the ratio of raccoon dog to human genetic material and ask if it’s correlated with SARS-CoV-2. If raccoon dogs were 10% of the genetic material in the genetic leaf-litter at our feet, then the truth is raccoon dogs account for 1/5th of the genetic leaves whereas after our lab protocol one sample with 5% humans might have a raccoon dog to human ratio of 2, whereas the one with 20% humans would have a raccoon dog to human ratio of 1/2.

Sampling protocols prevent us from inferring if there are correlations between any one animal’s genetic material and SARS-CoV-2, and the suppression of human genetic material means we can’t look at correlations between animal/human ratios and SARS-CoV-2.

What can we do with these data?

Not a lot.

We can identify the presence of raccoon dog genetic material in that leaf-litter, but metagenomic sequencing of that genetic leaf-litter could very well include raccoon dog DNA that persists for hundreds of years. We already know that raccoon dogs were sold at this market - they are sold in many markets. However, scientists have sampled raccoon dogs and found no reservoir, nor were surfaces more likely to test positive near animal vendors vs. vegetable vendors, nor do we have signs of a broader animal trade outbreak.

In other words, the presence of some animal’s genetic material tells us virtually nothing of epidemiological importance on the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

We can, however, look at what animals were in the market and prioritize surveillance of those animals as possible reservoirs. This procedure should be done systematically: don’t just scream “RACCOON DOG”, look at every single animal species in the leaf litter, examine correlations with SARS-CoV-2, and create a list of animal reservoirs to prioritize surveillance for SARS-CoV-2. After the Nipah outbreak in Kerala, India, colleagues and I produced such a list to point wildlife virologists towards probable reservoirs, and such lists may increase the efficiency of our search for reservoirs or, if the underlying data or analyses are wrong, they may put our wildlife virology teams on the wrong trail. Here, a list of reservoirs prioritized by metagenomic relative abundances or correlations with SARS-CoV-2 relative abundance is unlikely to be of great use because a mountain of other evidence strongly suggests the wet market was a site of transmission, not a site of spillover. Transmission could happen at PetsMart, you could metagenome-sequence the genetic leaf-litter at PetsMart, and you could use that to get a list of candidate reservoirs from bearded dragons to cats, and that list may be just about as useful as this reservoir-candidate list from the wet market.

Strongest evidence yet?

If I’m being a jerk - and for just one paragraph I would like to exercise my liberty to be a tongue-in-cheek jerk for your entertainment - I’d point out that the metagenomic surveillance is interesting & should be published, but it is no evidence at all. If this is the strongest evidence yet, it would (correctly) imply that there is no evidence for a zoonotic origin.

Okay, now my jerk-hat is off and my scientist hat is back on.

We measure the strength of evidence with a quantity called the “Bayes Factor”. To calculate the Bayes factor, we need to estimate the probability of seeing this evidence under our two theories. Let’s say researchers find an animal (e.g. a raccoon dog, but we’ll just call it “animal” for generality). The probability of finding an animal in an animal market, under the zoonotic theory of SARS-CoV-2 origin is

P(animal in animal market | Zoonotic) = P(Animal|Zoo)= 1

because we know there are animals in an animal market. Now, here’s where things get interesting (sarcasm). The probability of finding an animal in an animal market, under the lab-origin theory of SARS-CoV-2 is:

P(animal in animal market | Lab leak) = P(Animal|Lab) = 1

The Bayes factor is the ratio of these two quantities. A Bayes factor greater than 1 indicates evidence in favor of the hypothesis in the numerator, whereas a Bayes factor less than 1 indicates evidence in favor of the hypothesis in the denominator. Our Bayes factor is:

P(Animal|Zoo)/P(Animal|Lab) = 1

A Bayes factor of 1 means the evidence is not evidence at all. The Atlantic is calling this evidence the strongest evidence yet, but its Bayes factor is 1. Finding an animal in an animal market is not evidence that tilts the scales between these two theories.

That this is presented as “the strongest evidence yet” should tell us a lot about the complete lack of evidence for a zoonotic origin, in stark contrast to many lines of clear, consilient, and extremely strong evidence in favor of a lab origin.

We’ve estimated Bayes factors for other pieces of evidence. I’ll switch the numerator & denominator to express these Bayes factors in terms of the strength of evidence for a lab-origin:

P(Wuhan|Lab)/P(Wuhan|Zoo) > 50

P(FCS|Lab)/P(FCS|Zoo) > 1000

P(CGG|Lab)/P(CGG|Zoo) > 400

P(BsaI+BsmBI|Lab)/P(BsaI+BsmBI|Zoo) > 1,400

Combined, these four pieces of evidence produce a Bayes factor exceeding 1 billion. That, folks, is what strong evidence looks like. Genetic leaf-litter of an animal in an animal market is not strong evidence.

In conclusion:

SARS-CoV-2 most likely came from a lab, and The Atlantic’s report about a talk about data that nobody will share changes nothing. Many media outlets are ruining their credibility by broadcasting overconfident, unsupported claims otherwise. Gao et al. did a beautiful study, especially considering the circumstances.

As Gao et al correctly point out, the study finds the wet market is most likely a site of transmission, not spillover. Finding genetic evidence of animals in an animal market is uninformative, but the presentation of this evidence as “the strongest evidence yet” should tell you everything you need to know about the scientific debate and media biases.

I’d previously mentioned that reading the Proximal Origin paper felt like reading a propaganda piece. Reading the reporting on raccoon dogs feels the exact same way, except now everyone in the world can see it.

Stop shaming raccoon dogs, and start demanding for full investigations into coronavirus research that took place in Wuhan prior to the pandemic. Start counting the gene-leaves on the tables and in the test tubes in the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Thank you for breaking it down for those without a science background, talk about throwing the animals under the bus, is this agenda to rid the world of all living species beside humans? Nope not even going there

I find this post, and the one before on Bayesian analysis, to be the most strikingly objective pieces I've read during the pandemic. Everything else has a spin that can be felt. I sensed that you were truly open to letting the evidence lead you where it will. That's a *real* scientist... Thank you.